Students plant trees in Central Kenya.

Delphin King, Laikipia Wildlife Forum

Students plant trees in Central Kenya.

Delphin King, Laikipia Wildlife Forum

Students plant trees in Central Kenya.

Delphin King, Laikipia Wildlife Forum

Students plant trees in Central Kenya.

Delphin King, Laikipia Wildlife Forum

When the rain stops falling in Kenya, catastrophe strikes. The year 2009 hit the African nation with its worst drought in over 25 years. Crops were wiped out, entire herds of cattle killed. Farmers and livestock herders could no longer provide enough food for their own families, let alone the 23 million people across East Africa facing critical food and water shortages.

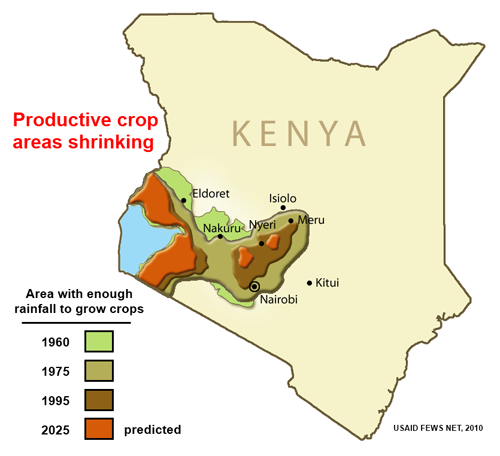

As a result of increased temperatures in the Western Indian Ocean, rainfall patterns in the region are changing, resulting in 30 percent less rain during the growing season. Even slight increases in temperature on land are making the dry conditions worse for farmers and herders by sucking coveted moisture from the soil. Crops and grasses become more difficult to grow. The higher temperatures also invite more and increasingly dangerous pests and diseases that affect people, livestock, and crops.

With much of East Africa’s population dependent on rain-fed agriculture, the negative impacts are felt by all. Lower yields are increasing prices for staple foods, like maize, and reducing revenue from key Kenyan export crops, such as tea.

These effects of climate change are expected to worsen in coming decades, adding additional stress to an already vulnerable and conflict-prone region. Rainfall is 10 percent to 50 percent below normal for this period in parts of Kenya. An estimated 2.4 million people are likely to require food aid.

USAID is meeting this complex challenge by helping East African farmers adapt their techniques to the changing climate to prevent these problems from reaching disaster levels. The Agency is also enabling farmers to mitigate rising temperatures through reforestation activities which, in turn, are providing them with much needed income, and helping to increase their resilience to the effects of climate change.

Conservation Farming

Leonard Manga and his wife Marion live near Isiolo in central Kenya. The lack of rainfall has made it difficult for them to grow maize, their staple crop. Recently, their traditional farming methods have resulted in low yields and sometimes even no harvest at all. But just last year, a USAID-funded project began teaching the Mangas and other farmers in the region a new set of conservation farming techniques called Kilimo Hai, or “Living Earth” in the local Swahili.

The International Small Group and Tree Planting Program is teaching farmers techniques like trapping rain water before it runs off, keeping soil moist, and reducing erosion so that soil nutrients are not washed away when the rain finally does fall. A seed loan program helps farmers acquire treated and certified seeds that help reduce the amount of pests in their fields.

After being trained in conservation farming, Leonard Manga and his family decided to try it on their land. They divided their maize farming area into two equal quarter-acre plots, and used the conservation farming techniques on one plot and traditional farming practices on the other. Despite their initial skepticism, the results erased all doubt: The conservation plot produced twice as much maize.

From the Forests to EBay

But better technique alone is not the magic elixir to mitigate the effects of climate change. The program also focuses on sequestering carbon through reforestation. Community groups plant trees locally and then sell the offsets generated by the carbon sequestered on the global carbon market. In Kenya alone, 52,000 group members have planted over 5 million trees. The carbon offsets derived from this work are sold on EBay and the revenue generated goes back to the farmers.

The carbon offsets have just been certified by the Verified Carbon Standard and the Climate, Community and Biodiversity Alliance, two highly regarded certifications for carbon offsets. “This dual certification was one of the first in the world and was possible because of USAID’s continued support,” says Kit Batten, USAID’s global climate change coordinator. “Not only does this program help to fight and offset carbon emissions, but the additional source of income helps make farmers less vulnerable to the economic effects of climate change.”

Weathering the Storm

Back in Isolo, Leonard Manga and his family have started inviting neighbors who didn’t practice conservation farming to his plots.

“I want my area to become a famine-free area. Maybe one day they will recognize me and award me a Nobel Prize,” he jokes.

Manga and other farmers are grateful for the seed loan. “Besides planting high-quality seeds, which we couldn’t have afforded otherwise, the treated, certified seeds are attacked less by the worms, unlike the home seeds which are vulnerable to the attacks.” Manga plans to sell some of his crop to establish a tree nursery and to put all of his land under conservation farming next season.

Although the scale of the problem is daunting, the Mangas are confident that even as the climate continues to change, their new skills will help them weather the storm.

FEWS NET: Weather Reports on Steroids

As USAID works to give Kenyan farmers the tools they need to survive in a changing climate, the U.S. Government is also taking a big-picture look at the nation's food security panorama, providing high-quality information on climate and weather patterns. But USAID's Famine Early Warning Systems Network is no simple forecasting tool with maps.

FEWS NET, as it is better known, collects and analyzes a variety of indicators—from weather patterns to food prices to droughts to armed conflicts—from every part of the globe, and then provides reports that predict how all those factors will impact vulnerable populations.

Its purpose is to help key decision makers plan ahead of potentially devastating events that leave populations at risk for hunger and famine. The reports are routinely updated with the latest developments—whether for better or worse.

For example, this June FEWS NET warned again that the humanitarian response to hunger in the Horn of Africa has not been sufficient. The region may be best known for catastrophic droughts that killed thousands in earlier decades, and the problem has not subsided.

“More than seven million people in the sub-region need humanitarian assistance, and emergency levels of acute malnutrition are widespread,” the report said. “This is the most severe food-security emergency in the world today, and the current humanitarian response is inadequate to prevent further deterioration.”

In Kenya, findings show that temperatures have increased and the long rains have declined, shrinking the areas that can support farming.

FEWS NET, which is 25 years old, maintains offices and staff in nearly 20 countries, including Haiti, Afghanistan, and several African nations.

Anyone can follow its forecasts at www.fews.net.

For the latest updates on the Horn of Africa drought, go to: www.usaid.gov/crisis/horn-of-africa.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.