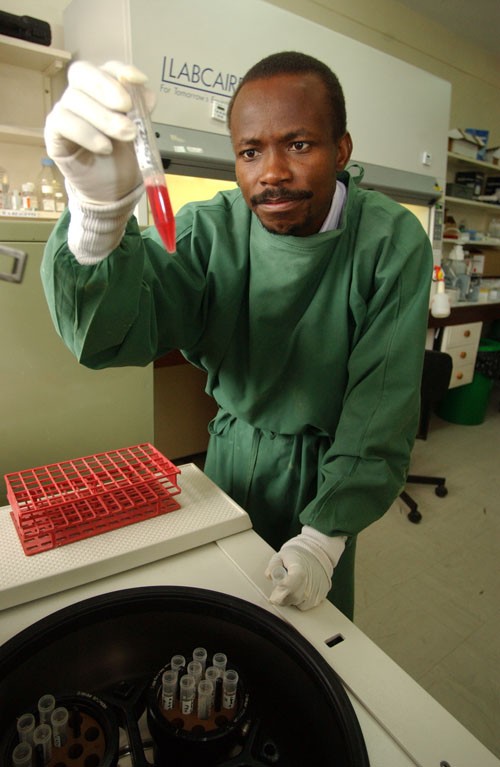

Dr. Gaudensia Mutua, principal investigator and medical manager at KAVI-Kangemi

Jean-Marc Giboux, Getty Images, courtesy of IAVI

Dr. Gaudensia Mutua, principal investigator and medical manager at KAVI-Kangemi

Jean-Marc Giboux, Getty Images, courtesy of IAVI

Dr. Gaudensia Mutua, principal investigator and medical manager at KAVI-Kangemi

Jean-Marc Giboux, Getty Images, courtesy of IAVI

Dr. Gaudensia Mutua, principal investigator and medical manager at KAVI-Kangemi

Jean-Marc Giboux, Getty Images, courtesy of IAVI

Numbers can be misleading. Take the recent hiring of 10 people by a couple of clinics operated by the Kenya AIDS Vaccine Initiative (KAVI) in Nairobi.

Given that Kenya has a population of 41 million and an unemployment rate that was above 40 percent last year, the recruitment of a doctor, data clerk, six nurses, and two lab technicians might seem inconsequential. But what it signifies for Kenya’s future in scientific research and technological innovation would qualify as something of a splash.

These hires are supporting new research projects at KAVI’s two clinics—one in Kangemi, the other at the sprawling Kenyatta National Hospital in Nairobi. The trials all started in the past six months and are run entirely by local staff. They include two Phase I HIV vaccine trials (see info box) supported by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI), through USAID, and one clinical trial examining treatment for a sexually transmitted disease, or STD. All three trials will be conducted concurrently by KAVI.

At the same time, KAVI’s scientists are conducting three pioneering research projects to explore immune responses in the tissue where HIV establishes a beachhead in the early phases of infection. All of this work is in addition to ongoing studies looking at the epidemiology and clinical course of HIV infection that the Kenyan scientists have long conducted with IAVI’s support.

Together, the nearly simultaneous launch of the new trials and studies amounts to a remarkable vote of confidence in the capabilities of the African researchers, and a tribute to the painstaking work—funded in large measure by USAID—that has gone into building a highly skilled team of experts in the field.

“It is very gratifying to see how our joint efforts over the years to build capacity for AIDS vaccine research are paying off,” said Dr. Gloria Omosa-Manyonyi, medical manager and principal investigator at KAVI. She has been with the initiative since its inception.

Laying the Foundations

Getting to the point where a true transfer of skills and technology is taking place has taken time and effort, but not because the scientists who founded KAVI in 1999 were new to HIV research.

Omu Anzala, KAVI’s program director; Walter Jaoko, the deputy program director; and the late Job Bwayo, co-founder and director, had already made names for themselves in the field. In partnership with colleagues at the University of Manitoba, they identified and studied sex workers in Nairobi who appeared to be highly exposed seronegatives—a rare subset of people who are free of HIV infection despite apparently frequent exposure to the virus.

By the late 1990s, Bwayo and his colleagues became interested in developing AIDS vaccines. Their hope was to develop one that would block infection by a strain of HIV most prevalent in Kenya.

At the same time, IAVI—which just marked its 15th year of operations—wanted to develop vaccines that were relevant to people everywhere, particularly those in the developing world, home to the majority of HIV infections. This would require establishing reliable research centers in developing countries capable of rigorously and ethically evaluating AIDS vaccine candidates. Because its interests coincided with those of the Kenyan researchers, IAVI suggested in 1999 that they join forces to evaluate one of the world’s first HIV vaccine candidates against one particular strain, clade A.

KAVI, the subsequent partnership, was born in 2001. A year later, the organization began the first AIDS vaccine trial in Kenya, evaluating a pair of vaccine candidates. While these candidates failed to generate immune responses strong enough for IAVI to continue their development, the studies were well conducted.

“We had faith in KAVI’s ability to conduct these studies, though that confidence wasn’t always shared by others,” said Gwyneth Stevens, IAVI’s director of clinical laboratories in Africa. “Some people in wealthy countries have a certain attitude toward the developing world: things just can’t be done quite as well in those places.”

Pioneer for Local Research

Inspired by its work in Kenya, IAVI began setting up partnerships for AIDS vaccine development in other countries. With the active support of funders, most notably USAID, IAVI worked with its research partners to build and refine research capacity. KAVI became the first site in what is today a highly sophisticated network of 11 IAVI-sponsored clinical research centers dedicated to testing AIDS vaccine candidates and conducting related HIV research in Kenya, Uganda, Zambia, Rwanda, and South Africa.

“Our program,” said Stevens, “has shown that given the right support, research labs in developing countries can work at standards as high as any you’ll find in the U.S. and Europe.”

The Kenyan trial also illustrated the important role training can play in vaccine development. If academic science thrives on sudden inspiration and back-of-the-envelope calculations, clinical product development depends on audit trails and standardized procedures.

“We had until then just done basic research,” said Bashir Farah, KAVI lab manager. “The way you do basic research is different from how you run clinical trials—[in basic research] you can change your experiments midway and try any number of different things until you get your answer. But in clinical trials you have to follow protocols. We had to get people used to this and to understand that we were aiming for certain standardization.”

Standardization, mainly through adopting a rigorous set of operating procedures and attaining international laboratory accreditation, became particularly important as IAVI began sponsoring vaccine trials and HIV research across Africa.

This emerging capability is no accident, but a basic tenet of USAID’s and IAVI’s approach to AIDS vaccine research in developing countries. In the last year, KAVI’s researchers and technicians have trained 140 people, including staff from the laboratories of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Kisumu and Nairobi, and are currently training another 30 researchers from Sudan, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Rwanda working with the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative.

An Elusive Vaccine

The development of an AIDS vaccine remains one of the greatest scientific challenges of our time, mainly due to the extreme mutability of the human immunodeficiency virus. If history is any guide, success in this endeavor is invaluable to the global campaign against AIDS. There are an estimated 34 million people living with HIV and, each day, an additional 7,000 people are newly infected by the virus.

“Based on all we have learned from tackling polio and eradicating smallpox,” says David Cook, IAVI’s chief operating officer, “we know that our best hope for curbing and eventually ending the AIDS pandemic, which has already claimed nearly 30 million lives, is through the deployment of HIV vaccines. I can think of few things as worthy of public support.”

After climbing steadily through much of the past decade, total global funding for AIDS vaccine research and development flattened out at $868 million in 2008 and 2009. As always, the U.S. Government provided the most substantial portion of that support—nearly $650 million in 2009, largely through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and USAID.

Researchers working on an AIDS vaccine have made significant strides in the past couple of years. In late 2009, U.S. military and Thai researchers announced that a candidate vaccine regimen they had assessed in a large clinical trial provided 31 percent protection from HIV. The protection was modest—not enough to seek regulatory approval—but it was the first demonstration in human studies that a vaccine can prevent HIV infection, and it generated considerable excitement in the field. Researchers around the world are today racing to improve upon those results.

At the same time, scientists have made major breakthroughs in the applied science of AIDS vaccine design. Just weeks before the Thai results were announced, researchers at IAVI and in the Neutralizing Antibody Consortium (NAC) it oversees reported in the journal Science that a highly collaborative effort involving some 1,800 HIV-positive volunteers, two biotechnology companies and research centers—including KAVI—in 11 countries had resulted in the isolation of a pair of novel antibodies capable of neutralizing a wide spectrum of HIV subtypes. These powerful antibodies hold important clues to the design of a potentially powerful AIDS vaccine

Since isolating those first two broadly neutralizing antibodies, IAVI and NAC researchers have discovered 17 new antibodies from blood samples gathered through their global hunt. Meanwhile, researchers at the Vaccine Research Center of the NIH have independently found a set of other such antibodies. The two teams are collaborating on these discoveries to design entirely new prototypes of AIDS vaccine candidates. Not only is an AIDS vaccine possible, but researchers now have the tools to understand what a vaccine must do in order to stop the virus.

Building “Meaningful Capacity”

To date, KAVI has completed four Phase I trials and one Phase II trial of candidate AIDS vaccines, and is in the midst of two additional Phase I studies. It now plans to capitalize on this experience to become a stand-alone research institute within the University of Nairobi—one that works with a broad portfolio of partners to conduct health intervention research, and perhaps leads to even greater residual effects on society.

“Strengthening scientific and technical capacity in the developing world has the potential to stimulate economic growth, particularly if new jobs are created that build local economies,” said Margaret McCluskey, senior technical advisor for HIV vaccines at USAID. “KAVI has been able to extend its work beyond HIV vaccine research and to develop partnerships with organizations addressing a variety of other health issues of importance to Kenya.”

As the search goes on, KAVI is also working with IAVI to make a name for itself in the arena of mucosal immunology. Immune responses located in the tissues where the virus enters the body may play a key role in preventing HIV infection from taking hold.

Being able to detect and measure immune responses on mucosal surfaces will become increasingly relevant to AIDS vaccine development, especially as vaccine candidates move to large-scale, efficacy trials.

“The fact that the KAVI team can do this level of very sophisticated science is more than just impressive; it’s evidence that USAID’s support of HIV vaccine research and development builds meaningful capacity—a cornerstone of sound and sustainable development. KAVI’s expanded portfolio is a quintessential example of how applied research for one disease can translate into collateral benefits when employed to investigate solutions for other diseases of relevance to the region,” said McCluskey.

IAVI is currently in the early stages of designing vaccine candidates to specifically elicit immune responses in the mucosal tissues that first come in contact with HIV. Research centers that test those candidates will have to be capable of consistently measuring them. In advance of these studies, IAVI staff trained KAVI researchers to collect and prepare mucosal tissue samples and use them to conduct highly standardized and accurate immunological laboratory tests, or assays.

“There has been a significant increase in both the scale of the work we do at the KAVI labs, and the kinds of tests and assays we conduct,” says the lab manager, Farah.

KAVI hopes that all this groundbreaking clinical research will put it on the map of both the study of vaccines and the human immune system, and help it become a center of excellence in HIV/AIDS research. Yet, for all its new ambitions, KAVI remains in hot pursuit of the trophy that inspired its creation: the development of an effective AIDS vaccine. That motivation isn’t likely to go away.

“Africa continues to bear the brunt of the AIDS pandemic,” said Dr. Gaudensia Mutua, the principal investigator and medical manager at KAVI-Kangemi. “It is only fitting that African scientists play a central role in finding a solution.”

Helen Thomson is clinical operation director for Africa, International AIDS Vaccine Initiative.

For more information, go to:

HIV/AIDS Trial Primer

Phase I trials enroll small numbers of people who are at low risk for HIV. The primary goal of these trials is to determine the safety of these products for human use.

Phase II trials enroll larger numbers of people and may include some individuals who are at higher risk for HIV. These trials often yield additional data on safety and side effects, and on immune responses to the vaccine among a larger population.

Phase III trials provide the most accurate test of whether a vaccine provides any protection against infection or disease. These trials generally compare the rate of infection in individuals given an experimental vaccine with the rate of infection in a group given a placebo, or a medicine that has no effect.

Source: IAVI

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.