A baby is treated by D-Rev's Brilliance device in a neonatal care intensive unit in Ogbomoso, Nigeria. The low-energy device uses strategically placed, high-intensity blue LEDs to treat severe jaundice in newborns.

Ben Cline, D-Rev

A baby is treated by D-Rev's Brilliance device in a neonatal care intensive unit in Ogbomoso, Nigeria. The low-energy device uses strategically placed, high-intensity blue LEDs to treat severe jaundice in newborns.

Ben Cline, D-Rev

A baby is treated by D-Rev's Brilliance device in a neonatal care intensive unit in Ogbomoso, Nigeria. The low-energy device uses strategically placed, high-intensity blue LEDs to treat severe jaundice in newborns.

Ben Cline, D-Rev

A baby is treated by D-Rev's Brilliance device in a neonatal care intensive unit in Ogbomoso, Nigeria. The low-energy device uses strategically placed, high-intensity blue LEDs to treat severe jaundice in newborns.

Ben Cline, D-Rev

The development lexicon is abuzz about innovation—which is quickly getting top billing on development blogs and digital bulletin boards. Innovation is also the focus of high-level Organization for Economic Development (OECD) ministerial meetings, World Bank reports and UNESCO workshops. And it is a key pillar of USAID Forward, the Agency’s reform campaign.

Not to be outdone, academia has issued a host of policy and white papers while business schools churn out case study after case study on innovation products, approaches, and business models. Everyone is asking the same question: What is innovation, what drives it, how do we accelerate it, and what new platforms promote it?

But exactly what does innovation really mean? It depends on who is answering. A recent Google search for the term “innovation” yielded 300 million hits. Is innovation only about applied science and technology? What about the latest wireless technology from Rwanda that alerts isolated local health clinics about infant HIV/AIDS blood test results from central labs and now connects 75 percent of the country’s 340 clinics, covering a total of 32,000 patients? Or is innovation also about just improving ongoing business processes?

A common description for innovation is that it is the introduction of a new idea, product, method, service, or approach that leads to significant, not just marginal, improvements.

Making the Old New

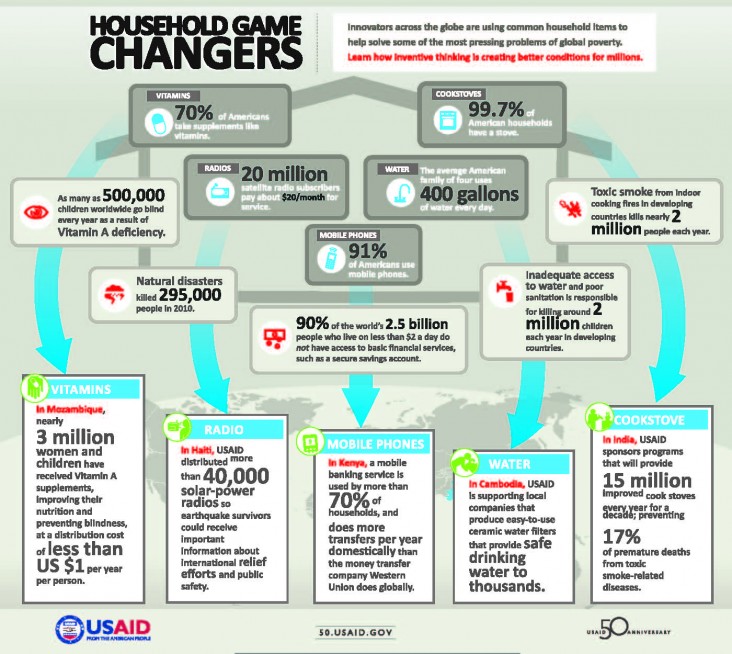

According to experts, innovation also can be an old good or service, so long as it has a fresh and novel use. A first-generation cell phone in Bangladesh that now allows for e-mobile banking is an innovation because it is being used for something other than just talking.

But not every new product or idea is automatically an innovation. To be innovative, the product or service must actually be used—not just a concept or a proof-of-concept. Plus, the way USAID thinks about innovation, according to Maura O’Neill, USAID’s senior counselor for innovation, it is also a question of scale.

“Innovation is about producing substantial improvements—not just incremental ones,” she says.

More than ever before, innovation is critical to reaching the billion or so people today who still live on less than $1.25 a day—with close to 380 million living in sub-Saharan Africa alone.

Organizations like USAID want to be hotbeds of innovation themselves, but increasingly they also want to leverage the largest set of thinkers possible to tackle a problem—an approach called “open innovation.” It’s based on the premise that solutions are no longer bounded within institutional, commercial, or donor “walls” or “silos.” Open innovation is a seismic change in thinking and anchored to the fact that knowledge is now widely distributed across oceans, countries, disciplines, and donors, as well as among experts from developed countries and those from resource-poor ones.

The growth of the Internet, the use of prizes and awards, a team approach to solving problems, and venture-capital markets all contribute to the amazing upsurge in open innovation approaches to achieve development success.

O’Neill put it this way: “We know that great ideas and development breakthroughs come from all different places—a lab in a university, an indigenous person who has deep local knowledge, or a passionate entrepreneur.” But often, she adds, it is “a combination of different people and organizations working together in new ways to create a way to identify and grow innovative ideas.”

A Revolution in Development Thinking

USAID is focused on finding ways to identify, replicate, and unleash advanced products and technological breakthroughs that help reach development goals quicker, cheaper, more effectively, and with lasting impacts. The Agency’s Development Innovation Ventures (DIV), for example, helps identify and accelerate the development of innovations that have the potential to reach 75 million people worldwide.

DIV, O’Neill goes on to say, “brings together diverse individuals from academia, the private sector, and NGOs to develop, rigorously test, and ultimately scale up promising approaches to improve the lives of the poor around the world.” DIV encourages advancement in all sectors from economic growth, to agriculture, to anti-corruption, to health promotion, and to better governance.

But DIV is just one of USAID’s efforts to be both innovative and support a revolution in development thinking. In the past, innovation has sometimes been seen as something only by, and for, the developed world. But some of the world’s poorest communities have always been great innovators—making life-enhancing improvements out of ordinary products. Development experts are quick to highlight these home-grown innovations: using spinning bicycle wheels to power cell phones, creating makeshift solar cookers from spare metal siding, and using ordinary cell phones to corner up-to-the-minute market prices for locally grown agricultural commodities.

Under USAID’s open-competition approach to innovation, anyone, anywhere in the world can apply for a DIV grant or submit a proposal for one of USAID’s Grand Challenges for Development. Innovation, in short, knows no geographic boundaries.

Along with the broader term, you will likely hear the phrase “reverse innovation.” This refers to the process where an innovation designed uniquely for the developing world finds its way back to the developed world with performance enhancements, not stripped-down features. These products create new untapped markets when they boomerang back to developed countries. Ultra low-cost laser eye surgery, hand-held, battery-powered cardiograms, tasty low-fat dried noodles, and the “Nano” car with a mind-blowing $2,000 price tag are often cited as reverse innovations.

USAID continues to take the lead among donors to make innovation fundamental to its re-vitalized development goals and reform agenda. Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple, summed it up nicely when he said “innovation distinguishes between a leader and a follower.”

Find out more about USAID and innovation.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.