Stephen A. O’Connell

Ending extreme poverty will require new ways of overcoming barriers to pro-poor economic growth.

I recently revisited Redistribution with Growth (1974), both on sentimental grounds–Hollis Chenery1 was USAID’s first chief economist–and to gain some perspective on the Agency’s new mission of ending extreme poverty. Chenery mentored a generation of development economists, including two of my own mentors, Lance Taylor and Larry Westphal.

Chenery’s goal in Redistribution with Growth was to make distributional objectives “an integral part of development strategy.” To an economic modeler, this meant two things: developing empirically grounded models of a country’s distribution of income (or consumption) over time, and replacing gross domestic product (GDP) with an explicit measure of welfare when evaluating development strategies and projects. These agendas—one basically technical, the other basically political, despite its technical guise—have come a long distance over 40 years, and reviewing some of the twists and turns can help us think through what lies ahead.

Redistribution with Growth provides a springboard for this essay’s two main points. The first is that ending extreme poverty will require new ways of overcoming barriers to pro-poor economic growth. These barriers were present in 1990—the “start date” for the Millennium Development Goal of cutting the global poverty headcount in half by 2015—but the intervening period has shifted the global composition of poverty toward countries with relatively weak institutions and resource endowments that bias their exports in favor of primary commodities and away from globally competitive employment. The so-called “resource curse” will have to be overcome if extreme poverty is to be eliminated. The second point is that smart redistribution policies have expanded the scope for efficient redistribution beyond what Chenery and his associates imagined. Such policies are likely to play an important role in achieving the goals of the post-2015 Development Agenda.

Redistribution with Growth in retrospect

Chenery’s concern in the early 1970s was that progress against poverty had been inadequate despite more than a decade of strong economic growth. The idea of replacing GDP with a welfare-based measure was equal parts elegant and radical. The argument was that economic planners needed a measure of development success that captured social attitudes toward poverty and inequality. Chenery and associates considered the growth rate of GDP inadequate for this purpose, because it violated what they viewed as a universal feature of social welfare judgments: The idea that a costless transfer of consumption from a rich household to a poor household would make the world better off.

Chenery and his co-authors argued that, instead of simply averaging the gains of different households or social groups (as done in calculating GDP per capita), planners should use “distributional weights” that were higher for poor households. Planners could provide an elegant grounding for the weights by specifying the degree of diminishing social returns to income. For example, if social utility were a function of the log, rather than the level, of individual incomes, the weights applied to gains or losses of different income groups would be inversely proportional to income.2

Distributional weights never came into regular use by economic modelers, and were rarely applied (after a brief period of enthusiasm) in the cost/benefit analysis of public investment projects. As one of Chenery’s successors at USAID observed, this was not because development economists didn’t care about poverty. The problem was that no technical basis existed for consensus on the appropriate weights.3 My guess, however, is that Chenery and his co-authors lost little sleep over the short half-life of distributional weights. The spirit of the idea was what mattered. Spurred on by the thinking in Redistribution with Growth, economists were proceeding with many alternative ways of formalizing distributional concerns.

Regrettably, Chenery died in 1994, too early to see the triumph of his broader agenda in the policy realm. He may have had an inkling in 1974 that events would intervene; his introduction to Redistribution with Growth speaks forebodingly about the 1973 increase in energy prices. But he could not have anticipated that the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s and the oil price shock of 1973 to 1974 would be followed by nearly two decades of global economic turmoil. Distributional concerns would be swept to the margins as the developing world—particularly outside of Asia—entered an extended period of crisis and market-based economic reforms.

Gradually, however, the consolidation of policy reforms and the limitations of the structural adjustment paradigm brought Chenery’s concerns back to the fore. The markers of this process gathered pace during the 1990s: The World Bank published its first international poverty line in 1990; the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper process for multilateral debt relief was initiated in 1996; and the Millennium Development campaign began in 2000. Throughout the 1990s, developing countries introduced innovative social protection programs to promote asset accumulation among the poor and protect them from the effects of macroeconomic crisis.

Fast-forward to USAID’s new mission statement, with its striking reference to ending extreme poverty. The World Bank’s newly adopted dual mission pairs a similar commitment with a focus on “shared prosperity,” defined in terms of the income growth of the lowest two quintiles.

In my own view, no single idea has done more to unify the global development community since the early 1990s than the idea that distributional objectives should be integral to development strategy.

A shifting target

The clarity and prominence of recent commitments are triumphs of the political component of Chenery’s agenda. But Redistribution with Growth was as much about mechanisms as it was about goals. Planners needed a reliable way to model the distributional consequences of alternative policy choices, and—in Chenery’s view—this required new data and new analysis.

Forty years later finds us in an immensely stronger position on the microeconomics of poverty and the impact of targeted interventions in areas like finance, education and health. But, to apply Chenery’s lens: What does a poverty—eliminating development strategy look like? I’ll stress two findings that would have surprised Chenery in 1974—and that bear importantly on what lies ahead.

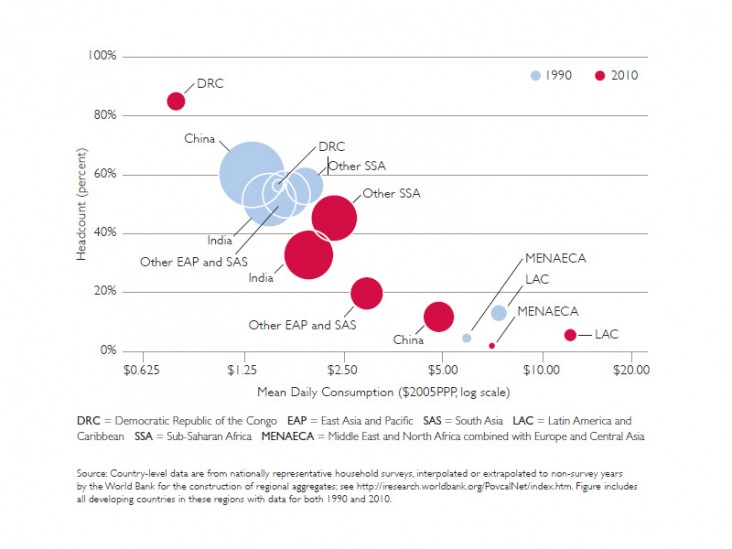

Figure 1 summarizes the evolution of poverty on a regional basis since 1990. The vertical axis shows regional- or country-level headcount ratios, defined as the proportion of a population with consumption under $1.25 a day at 2005 international prices. The horizontal axis shows average consumption per capita, measured on a log scale so that equal displacements along the axis represent equal amounts of economic growth. The diameters of the circles are proportional to the number of poor in each location.

Source: Country-level data are from nationally representative household surveys, interpolated or extrapolated to non-survey years by the World Bank for the construction of regional aggregates; see http://iresearch.worldbank.org/PovcalNet/index.htm. Figure includes all developing countries in these regions with data for both 1990 and 2010

Two observations leap from this picture. The first is the importance of economic growth, particularly in China, to the successful achievement of the income poverty goal of the Millennium Development campaign. Average consumption grew so rapidly in China that the nation’s poverty headcount fell by roughly three-quarters, despite an increase in inequality. What would have surprised Chenery, I think, is the robust power of economy-wide growth for increasing the incomes of the poor. Data across countries from repeated household surveys show no systematic tendency for the distribution of consumption to worsen with growth. In addition, distributional changes in either direction typically have been much less important than overall growth in changing poverty headcounts.

No consensus exists on the reasons for these findings. In this crucial respect, the development research community has yet to respond to Chenery. However, unless these correlations change substantially over the next 15 years, what will matter most for eliminating poverty is the achievement of rapid economic growth in the countries where the poor now live.

The second observation conveyed by Figure 1 is that 20 years have altered the geographical location of the poor. On a regional basis, Asia has given way to sub-Saharan Africa. A key feature of this shift is that the poor are increasingly located in countries with large rents on the export of primary commodities, defined as the difference between the value of the exports and the cost of the resources required to extract them.

Primary-commodity rents are an easy source of government revenues that can help drive growth through public investments in security, infrastructure and human capital. Chenery, with his economic planner’s mindset and little systematic evidence to the contrary, would likely have viewed commodity wealth as a clear development opportunity. But global evidence since the early 1970s suggests that this kind of wealth has tended, on balance, to undermine economic growth.

Among the numerous potential channels of the “resource curse,” three stand out when thinking of implications for the poor. One is economic: In an era of globalization, primary commodities tilt the economy away from the manufactured goods and traded services that generate internationally competitive jobs and economy-wide productivity gains. One is political: Resource rents allow a political elite to subsist without delivering useful public services in exchange for tax revenues, an exchange that many political scientists view as fundamental to the construction of state capacity and legitimacy. The third lies at the intersection of the economic and political: Resource wealth can be a prize that supports the recruitment of underemployed young men into political violence.

The Democratic Republic of Congo illustrates the intersection of all three effects. This nation was not a major nexus of global poverty in 1990; it is now.

Although economic growth is a high-level objective of U.S. development assistance,4 it is not uniformly a focal point of U.S. Government programming at the country level. Among low-income countries, those that qualify for a Millennium Challenge Corporation Compact are guaranteed to have a strong growth component. This set is limited by construction, however, to countries that meet demanding—although income-adjusted—standards of institutional quality. It excludes many of the countries where the poor now live.

This allocation may be the right concession to reality, given our limited understanding of growth dynamics n difficult places and our limited policy leverage in the presence of resource wealth. However, it suggests high returns, when implementing USAID’s extreme poverty agenda, to understanding the experiences of the few countries—such as Indonesia, Chile and Botswana—that have achieved sustained and rapid growth from a primary commodity base. It also underscores the crucial importance of initiatives like Power Africa that address known constraints to growth.

Assets and cash transfers

Chenery and his co-authors argued that the best distributionally weighted development strategies over a horizon of a decade or more were those focused on increasing the assets, rather than the consumption, of the poor. Since outright reallocation of existing assets was either politically infeasible—as in land reform absent a revolution—or impossible (reallocation of human capital, for example), strategies should focus on enhancing the capacity of the poor to access public infrastructure and to invest in assets including land, education and health.

USAID’s portfolio in low-income countries— with its emphasis on health, physical capital, education and the productivity of smallholder agriculture—is well aligned with these broad priorities. In fact, it may be particularly well aligned in countries where the policy pathways to broad-based growth are unclear and where development partners can help create the infrastructure and human capital platforms for future growth. The experiences of Indonesia, Chile and Botswana suggest, however, that such efforts need to be complemented with initiatives to increase fiscal discipline, enhance the transparency of public financial management and support the rigorous evaluation of public investment projects.

Writing in the early 1970s, Chenery and associates placed less emphasis on the detailed design of redistribution programs than on the need to realign government priorities and redirect development research. First things first: If the economic and political costs of redistribution were large, then getting to the design step required a combination of stronger political motivations and improved models that could quantify distributional outcomes.

Starting in the mid-1990s, however, innovative social protection programs began to open up new avenues for “smart” redistribution, defined as politically sustainable redistribution with low administrative costs and high efficacy in reaching the intended beneficiaries. One example is conditional cash transfer programs, which have been implemented worldwide following the success of Mexico’s Progresa/Oportunidades program. With their emphasis on pairing income support to low-income mothers with investment in the human capital of their children, these programs epitomize the Redistribution with Growth approach.

Looking ahead, information technology will expand the scope for transformative redistribution policies. In countries with weak institutions and large commodity rents, for example, the technological barriers to a very different type of transfer program, involving the pro rata distribution of a modest portion of natural resource revenues directly to citizens, are rapidly eroding.5

Imagine, for example, if all citizens of the Democratic Republic of Congo could rely on a regular cash transfer financed from mineral revenues. Such transfers would be distributionally progressive by definition—and more so with a greater initial degree of income inequality. Moreover, the limited existing evidence suggests that the distinction Chenery and associates drew between consumption transfers and “investing in the poor” was too stark. Cash transfers increase asset accumulation by the poor even when beneficiaries are free to allocate their transfers as they wish. If such a system altered political dynamics in a growth-promoting way, the prospects of the poor would improve even more dramatically.

Stephen A. O’Connell is the chief economist at USAID. The views expressed in this essay are his own and do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

1 Hollis Chenery, Montek S. Ahluwalia, C.L.G. Bell, John H. Duloy, and Richard Jolly (1974), Redistribution With Growth (Oxford: Oxford University Press). By the early 1970s, Chenery had moved (via Harvard) to the World Bank, where he became the Bank’s first and longest-serving chief economist and vice president for development economics research.

2 The log transformation was later adopted by the UNDP in the construction of its Human Development Index.

3 Arnold Harberger (1978), “On the Use of Distributional Weights in Social Cost-Benefit Analysis,” Journal of Political Economy 86(2), Part 2: Research in Taxation: S87-S120.

4 Presidential Policy Directive 6, Sept. 22, 2010 (http://fas.org/irp/offdocs/ppd/).

5 Unlike conditional cash transfers, such transfers would be neither targeted nor conditional. Todd Moss and the Center for Global Development have championed this idea: see http://international.cgdev.org/initiative/oil-cash-fighting-resource-curse-through-cash-transfers.

Frontiers in Development

Section 3: Catalyzing Growth and Investment

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.