Jerrod Mason

Improving the quality of public investments in developing countries is crucial to ending extreme poverty within the next generation. Investments in education, health and public infrastructure promote broad access to economic opportunities and have the potential to help individuals and firms increase productivity and mprove lives—but they must be efficient and effective.

Many partner governments, however, lack the capacity to evaluate investment options and select those with the greatest benefits. Donor agencies, which regularly apply economic analysis to their own development investments, should support a concerted effort to build this capacity.

Development organizations—including USAID—have long recognized the importance of applying cost-benefit analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, or other forms of economic analysis to their own investments to safeguard against poor decision-making and maximize the impact of their development dollars.

Over the last 25 years, however, donor-funded activities have declined dramatically as a share of total capital inflows into the developing world. In this new landscape, the biggest lever that development agencies hold is not improving the effectiveness of their own spending—important as that is–but rather improving the ability of host governments to evaluate and select the most effective investments.

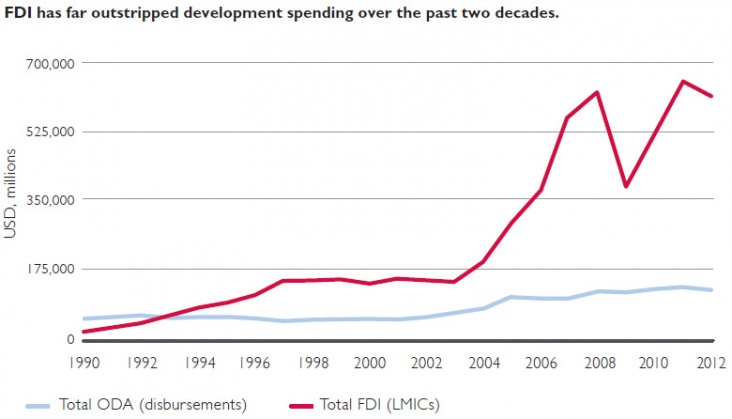

Donor investment is declining in relative importance

Between 1990 and 2012, total official development assistance (ODA) to lower- and middleincome countries grew at an annual rate of about 4 percent. By contrast, foreign direct investment (FDI) to lower- and middle-income countries increased by about 16.5 percent annually over the same time period.1, 2 As a result of this massive growth, FDI flows to the developing world in 2012 were nearly five times larger than all ODA flows combined.

In addition to the massive expansion of foreign private investment all over the developing world, developing-country governments have begun to access domestic and foreign debt markets, many benefiting from lower overall debt levels as a result of the Highly Indebted Poor Countries Initiative. Within the last decade, sovereign foreign-currency bonds have been issued on international markets—attracting strong demand at relatively low prices—by the governments of Ghana, Gabon, Nigeria, Zambia and Rwanda.

Finally, developing-country governments have increasingly turned to public-private partnerships to finance projects in investment-intensive sectors such as power, water, transport and information and communications technology. Growing incomes in many countries and the lure of new markets create strong incentives for private-sector investors. Meanwhile, governments and their people benefit from increased competition and expanded access to goods.

This sea change in external finance has had, and will continue to have, a fundamental impact on bilateral and multilateral development agencies. Donor-directed funds no longer account for the lion’s share of foreign capital flows and public investment into many of the developing countries in which USAID operates. For instance, Kenya’s government budgets between FY 2010–11 and FY 2012–13 called for an average of about $4.6 billion in government-financed development spending each year.3 During that same period, total annual official development assistance to Kenya averaged approximately $2.25 billion, or less than half as much as the Kenyan Government development spending. Public-private partnerships and private investments influenced by the Kenyan Government through policy and regulation-setting have further reduced the relative role of donors in the investment landscape.

While making better decisions regarding design and management of donor-funded or financed projects remains key to poverty reduction, it is no longer the only important source of investment that must be considered.

Improving partner country investment decisions is crucial

Although many developing-country governments have made strides in improving domestic resource mobilization and in accessing financial markets, they still face real budget constraints and cannot afford to waste their investment dollars. Countries that make prudent public investment decisions at both the strategic and project levels can usher in a future of dynamic, poverty-reducing growth, while those that do not may suffer from anemic or narrowly shared growth that fails to broadly improve overall living standards.

There is rightly a great responsibility for developing-country governments to manage investments wisely. These include investments undertaken within national development budgets, funded through domestic resources or through debt offerings. They also include private investments that require some government cooperation or direction, such as public-private partnerships for infrastructure development. For the latter types of investments, private investors ensure a financial return for their stakeholders, but governments should also ensure that the project benefits society as well.

One important way to improve the quality of investments in developing countries is to build capacity within government ministries, implementing partners, civil society and academia for rigorous investment appraisal. These efforts have the potential for enormous returns, as publicly financed and directed investment continues to play a larger and larger role in facilitating (or in limiting) economic growth.

Sustained efforts are needed to build appraisal capacity

Some USAID missions have begun to recognize the power of this type of capacity building and have hosted country counterpart trainings in economic analysis. Over the last two years, USAID’s Bureau for Economic Growth, Education and the Environment, working in cooperation with missions, has conducted intensive training in cost-benefit analysis and other forms of economic analysis for government counterparts in South Africa, Afghanistan, Haiti and Kenya.

Through courses tailored to fit host country needs, participants gained hands-on experience in developing economic analyses of actual development projects in their own countries—gaining the tools for making better public investment decisions. USAID employees participated in these trainings as instructors and students, working with their host country counterparts to build a foundation for future cooperation on the design and analysis of public investments. One example is a two-week cost-benefit analysis course that took place in Afghanistan during February 2014. Among the course’s 29 participants were 12 from the Afghan Government, representing the Ministry of Finance and line ministries, and the Afghan water and power utilities.

Through hands-on case studies, participants learned how to conduct financial and economic analyses of projects and gained experience in building, interpreting and using the results of costbenefit analysis models for decision-making. These are the skills needed for identifying, designing and managing effective projects that maximize the social benefits of public investments. Moreover, participants evaluated actual investments in their own countries and selected alternatives with the greatest societal benefits.

These few examples of host-country training initiatives occurred in the absence of any broader strategic focus at USAID to encourage these efforts. A few ad hoc training courses, however, will not create the institutional change necessary to achieve further large gains in poverty reduction. To address this need, the USAID mission in Afghanistan is pursuing a longer-term mechanism for providing ongoing local-language instruction in economic analysis to Afghans in government, civil society and academia on a longer-term basis. The USAID mission in Haiti is developing a similar program.

There is rightly a great responsibility for developing-country governments to manage investments wisely.

USAID is also partnering with institutions on the ground to build their capacity for teaching economic analysis of public investments. The USAID mission in Kenya recently worked with the Kenya School of Government to design and conduct a course for government officials on analyzing power sector investment and regulation. Future capacity building programs evaluate a range of training alternatives to identify the most effective options.

These types of longer-term training programs can yield huge benefits as governments learn how to design and manage their investments more effectively. Additionally, offering civil society organizations and other groups access to these tools strengthens the ability of citizens to hold governments accountable for the impact of public spending. Members of society who understand the impacts of public investment are better able to defend their rights and interests as decisions are being made about how public funds are spent. In this way, building the capacity for evaluating investment options outside of government helps ensure that benefits are widely shared and contribute to extreme poverty reduction, rather than benefiting the few at the expense of the many.

Strengthened capacity for economic analysis is no panacea for poor government accountability; reforms that encourage government transparency and the rule of law and curtail the influence of entrenched interests are often key pieces of the solution as well. However, equipping groups across society with the tools to challenge ineffective or misdirected spending is an important step in reducing the undue influence of entrenched interests in many developing economies.

Conclusion

Development agencies must continue to improve the quality of their own investments and to increase their impact on poverty reduction. However, we must look beyond simply increasing the impact of an official assistance portfolio that represents a continually shrinking piece of the overall development pie. Instead, donors should consider how to improve the effectiveness of all investments in developing countries. Building local government and stakeholder capacity for economic analysis is a vital step. Such an effort is crucial for achieving our goal of eliminating extreme poverty. It’s time we get serious about making it happen.

Jerrod Mason is an economist in USAID’s Bureau for Economic Growth, Education and Environment. The views expressed in this essay are his own and do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

1 World Bank, “World Development Indicators,” 2014. [Online]. Available: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/views/variableSelection/selectvariables.aspx?source=world-development-indicators. [Accessed 20 03 2014].

2 OECD, “QWIDS,” 2014. [Online]. Available: http://stats.oecd.org/qwids/. [Accessed 20 03 2014].

3 Kenya Ministry of Finance, “Budget Reports for FY 2010–11 to FY 2012–13.”

Frontiers in Development

Section 3: Catalyzing Growth and Investment

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.