Christopher Powers and William M. Butterfield

Inclusive economic growth is vital to eliminating extreme poverty. When average incomes rise, incomes in the poorest two quintiles increase proportionately, according to Growth Still Is Good for the Poor, an August 2013 World Bank report.1

So what, in turn, drives economic growth? Private investment is critical because it expands demand while also enhancing supply in a country’s economy. Foreign direct investment (FDI) is one type of investment flow that not only transfers money across borders but knowledge and best practices as well.2 Following the global financial crisis of 2008, FDI flows to the developing world recovered, reaching a new high of $759 billion in 2013 that far surpassed official development assistance flows of $150 billion in 2012.

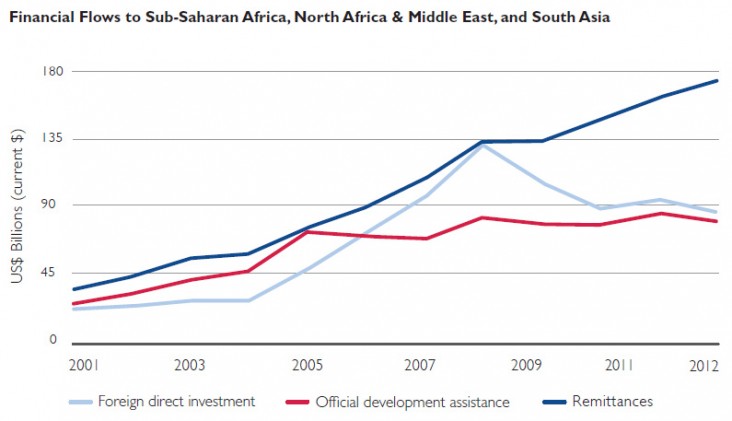

Yet FDI has not recovered in the poorest countries, which are being left behind. The regions of sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa, and South Asia combined represented just 6 percent of the world’s total FDI, an amount similar to development assistance and well below remittances (Figure 1).3

Booming remittance flows have eased the burden of poverty by putting money directly into people’s hands. However, individuals most often use remittances for consumption rather than investment and remittances do not appear to be associated with long-term economic growth according to research by the International Monetary Fund.4

The poorest countries need private investment

Private investment can be constrained by a number of factors, including weak macroeconomic policies, high costs of doing business, poor financial intermediation and political instability. Banks within many developing economies, such as Egypt and Pakistan, operate as a primary source of financing for the government. When a substantial portion of a bank’s balance sheet goes to financing large budget deficits, the cost of borrowing goes up, and entrepreneurs are “crowded out” of access to capital.

In addition, domestic financial institutions may be unwilling to lend to new businesses because they view new areas or sectors as too risky or because they fail to see the potentially profitable opportunities. Banking standards, although critical for risk mitigation, can restrict lending and force small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to rely on informal, and more costly, modes of financing. The financing such firms often do receive is highly collateralized short-term working capital rather than capital targeted for growth.

To counteract these constraints, development organizations must service the missing links that will catalyze private investment deals that otherwise would not have taken place. This is the essence of “crowding in,” and ways of doing so include:

- Creating or seeding investment funds

- Incentivizing local financial institutions through credit guarantees

- Partnering with local institutions that are well positioned to help entrepreneurs and startups

- Partnering with larger private-sector firms to scale up investments with shared commercial and development benefits

- Providing technical assistance to help companies strengthen business management and advocate for the removal of legal and regulatory barriers that limit private investment

Directly seeding investments

In some nations, domestic financial institutions are unable to invest in businesses because of underdeveloped markets or capital flight. Donor organizations can fill these gaps by allowing local investment funds to manage assistance resources or by developing their own funds. Such funds must simultaneously consider development and commercial priorities. In other words, they must have a “dual bottom line” and only undertake profitable investments that also produce meaningful social returns and demonstration effects that validate and encourage expanded private investment.

Direct investment with USAID funds began after the fall of the Soviet Union and in response to market liberalization in Eastern Europe. The U.S. Congress authorized nearly $1.2 billion for 10 Enterprise Funds, managed by proven investors, to support private firms in the region. The Enterprise Funds succeeded in producing some impactful demonstration effects, supporting the establishment of debt and equity markets in previously Communist countries and collectively leveraging $6.9 billion in private capital over their two-decade lifespan.5

Newly established USAID direct investment funds in Egypt, Tunisia and Pakistan have the opportunity to build upon these successes while supporting SMEs through the demonstration of innovative financing mechanisms. For example, “mezzanine” products that mix debt and equity can benefit investors by reducing risk while allowing them a share in the revenues and profits of investees. SMEs in turn gain access to capital without having to manage the broadening ownership and increased level of sophistication that pure equity financing requires.

Using guarantees to enhance credit and confidence

Where domestic financial institutions are able but unwilling to increase access to finance, development organizations can indirectly invest by incentivizing local banks through credit guarantees that protect a percentage of a bank’s portfolio against default. USAID’s Development Credit Authority (DCA) has had significant success getting debt-based financing into the hands of previously unserved borrowers.

Yet there are opportunities for DCA to not only engage in the aforementioned debt products, but also be more proactive in reducing risks to equity investors in new markets. For example, through a partnership with J.P. Morgan Chase, DCA guaranteed an $8 million loan to an equity investment fund for SMEs in East African agriculture markets. The guarantee was supported by a $17-million equity investment from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Gatsby Charitable Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation. This arrangement also included $1.5 million in USAID Feed the Future technical assistance resources, a superb example of development impact investing aimed at poverty alleviation.

DCA can also help turn remittances into investment through guaranteeing the issuance of “diaspora impact bonds,” sold mainly to nationals working abroad. The bond proceeds fund development projects in sectors such as health and education. Meanwhile, bondholders reap returns while contributing to poverty alleviation in their home countries.

Recently, some countries have issued diaspora bonds, most notably Kenya and Ethiopia. Yet most investors still see the product as high risk. By offering a partial guarantee (usually 50 percent) on the repayment of the bonds, DCA could help mitigate this perception and encourage social investment.

Guaranteeing equity-based investments and sub-national bonds is admittedly risky. However, with a default rate of less than 2 percent on its guaranteed 67loan portfolio, DCA so far has collected more in fees from banks than it has paid out in defaults. USAID should therefore continue to structure guarantee products more aggressively to fill financial gaps.

Accelerating partnerships for investment

Credit guarantees cannot compensate for obstacles SMEs often encounter, such as lack of credit qualifications and audited financial statements. Commercially driven “accelerators” (or incubators) can play a role. By taking an ownership position in the firm and providing business development resources, these organizations can help SMEs access formal financial markets or obtain funding from individual (“angel”) investors.

Accelerators and angel investor groups, however, may lack the information, capacity and coordination to function most effectively in this role. USAID is filling this gap through broader engagement. For example, USAID’s Partnering to Accelerate Entrepreneurship and the Middle East North Africa Investment Initiative support investors and businesses with co-investment and matching capital approaches as well as relevant technical assistance.

In addition, USAID’s Global Development Alliance6 partners with larger firms to help SMEs overcome local risks and capacity constraints—leveraging over $2.5 billion in private investment to date.7 For example, since 2005, USAID has collaborated with Coca-Cola for clean water development projects (a shared commercial and development interest). Existing USAID development programs (e.g., improving water resources management) complement Coke’s investments and vice versa, all in collaboration with other donors and host-country governments.

USAID’s new position of field investment officer responds to the need to develop more private-sector partnerships like this one. These mission-based foreign service officers use their knowledge of the business and development worlds to identify areas where the private sector and USAID can work together to achieve commercial and development success.

Strengthening policy and business management

Technical assistance is a critical component of any crowding-in strategy, particularly when it equips local businesses and other stakeholders with the finance and management skills needed for growth. Assistance should also be used to generate demand-driven reform of key policy bottlenecks that local firms face, making doing business easier.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) has successfully employed such an approach through its complementary Business Advisory Services facilities. These services give SMEs reduced-cost access to local and international business consultants while the Legal Transition Programme aids them in identifying and overcoming policy and institutional impediments to their investments. Both the EBRD and USAID are helping the Social Fund for Development in Egypt strengthen its capacity to serve as the main government authority on SME policy reform—further improving the investment climate for their SME technical assistance programs.

Moving forward

Other U.S. Government institutions should also look to increase efforts to crowd in private investment. The Millennium Challenge Corporation8 has recently explored ways to structure its compacts’ resources to attract higher levels of private-sector co-financing.

The Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC),9 which has turned a net profit for 35 years in a row, holds the ability to combine financing, guarantees and technical assistance in ways that make more and larger deals possible. Yet OPIC is legally prohibited from making minorityshare equity investments—an authority allowed to most of its peer institutions in Europe. This excludes OPIC from many potential deals and limits its ability to scale up its efforts while limiting U.S. businesses’ access to frontier markets.

Leveraging private investment to fight poverty is no easy task. The constraints are myriad and complex. However, by supporting innovations that utilize development assistance to “crowd in” private investment, USAID and partner institutions can get resources into the hands of the local firms and individuals that need them and spur the inclusive economic growth that reduces poverty.

Christopher Powers is a regional investment officer for USAID in the Middle East/North Africa region. William M. Butterfield is mission economist for USAID/Pakistan. The views expressed in this essay are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

1 David Dollar, Tatjana Kleineberg and Aart Kraay, “Growth Still Is Good for the Poor”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, August 2013 Available at: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/ WDSContentServer/IW3P/IB/2013/08/13/000158349_20130813100 137/Rendered/PDF/WPS6568.pdf%20

2 Michael Klein, Carl Aaron and Bita Hadjimichael, “Foreign Direct Investment and Poverty Reduction,” World Bank Policy Research Working Papers, June 2001. Available at http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/ book/10.1596/1813-9450-2613

3 World Bank, World Development Indicators.

4 Adolfo Barajas, Ralph Chami, Connel Fullenkamp, Michael Gapen and Peter Montiel, “Do Workers’ Remittances Promote Economic Growth?” IMF Working Paper, July 2009. Available at: http://www10. iadb.org/intal/intalcdi/pe/2009/03935.pdf

5 The Enterprise Funds in Europe and Eurasia: Successes and Lessons Learned. USAID, September 2013.

6 GDA is a form of public-private partnership whereby shared interests are identified and USAID and private sector partners agree to contribute toward the cost of a project, at minimum on a 1:1 basis.

7 Evaluating Global Development Alliances, DAI. Available at http://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1880/GDA_Evaluation_reformatted_10.29.08.pdf

8 The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) is an independent bilateral U.S. foreign aid agency, established by Congress in 2004, which applies selection-based criteria and a country-led approach to its assistance, which it delivers through “compacts.”

9 OPIC is the U.S. Government’s development finance arm. It provides debt-based financial products, political risk insurance and seed money for investment funds to help American businesses expand into developing countries.

Frontiers in Development

Section 3: Catalyzing Growth and Investment

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.