An iRead student at a primary school in Ghana gets to know his new Kindle and the dozens of books that come with it.

Worldreader

An iRead student at a primary school in Ghana gets to know his new Kindle and the dozens of books that come with it.

Worldreader

An iRead student at a primary school in Ghana gets to know his new Kindle and the dozens of books that come with it.

Worldreader

An iRead student at a primary school in Ghana gets to know his new Kindle and the dozens of books that come with it.

Worldreader

In the developing world, a quiet revolution is taking place in education: mobile devices are multiplying by the minute and bringing with them unprecedented access to educational resources.

Students in rural Africa are downloading eBooks while sitting in classrooms that scarcely have electricity. Newly literate girls in Pakistan’s distant Punjab districts are stretching their reading and writing skills by participating in text message-based discussion forums. As network coverage continues to expand and reach more of the world’s population, the possibilities seem endless for delivering truly incredible volumes of rich academic content.

This revolution is upending history, where progress is often hinged on the availability and affordability of resources. Over the last decade, however, mobile technologies have helped people living in the most resource-starved environments leapfrog over old barriers.

Entrepreneurs, public sector leaders, and field practitioners are on the lookout for the best and most cost-effective ways to take advantage of the new mobile environments. So is USAID.

In collaboration with a diverse international stakeholders group, the Agency is launching the m4Ed4Dev Alliance (Mobiles for Education for Development Alliance), which will serve an important role in the exchange of knowledge regarding mobiles for education in developing countries for project implementers, researchers, and leading thinkers. The actors will share practices in the use of mobile technologies for education, discuss the successes and lessons learned from these projects, consider the future of mobiles in the evolving education panorama, and provide an opportunity for USAID staff to explore potential projects that align with the goals of the Agency’s new education sector strategy.

“At USAID, we’re enormously excited by the opportunities that mobile technologies and devices can provide for supporting quality education outcomes,” says Anthony Bloome, an education technology specialist with USAID’s Office of Education who is coordinating the creation of the m4Ed4Dev Alliance, and symposiums, research roundtables, and monthly seminars on the topic.

“There is perhaps no more single important development intervention that has taken hold over the last 15 years than the mobile phone,” said Administrator Rajiv Shah at an August symposium in Washington, D.C.

Broadly defined, the range of mobile technologies includes cellphones, tablets, PDA devices, micro-projectors, and eReaders, among other technologies.

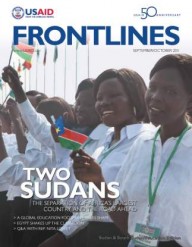

A recent m4Ed4Dev seminar highlighted the iRead project being implemented by Worldreader in several schools in Ghana. More than 500 students of various ages in six primary and secondary schools in Kade and Adeiso are already using their Amazon Kindle 3s in the iRead project. These eReader devices, available in schools and for students to check out to share with their families, are provided with approximately 80 reading titles already loaded; through cellular networks and wireless systems, students can download more than 1,000 additional titles. Children are also provided with reading lights so they can use their Kindles after the sun goes down.

“The Worldreader (iRead) students are reading more than in our wildest dreams,” said David Risher, president and co-founder of Worldreader, a charitable organization whose mission is to bring books, and thus promote literacy and a culture of reading, to children and families in the developing world.

The current cost is just over $200 per Kindle, which includes the e-reader, case, light, and loaded textbooks and storybooks (and access to many more.) The per-student cost is coming down quickly: e-readers cost $400 two years ago, and the price is expected to halve again in a year. Students often share the e-reader with friends and family, increasing the cost effectiveness even more.

“If we can figure out how to put in the hands of every single child everywhere around the world the capacity to have all the information they need to learn and grow, at no or low cost, we will have created a breakthrough that will last for generations,” said Shah.

Today, USAID/Ghana is working to evaluate and more thoroughly understand the impacts of the iRead project as it progresses. For example, the mission is looking at reading improvements and the relative costs of supplying and using reading materials in print versus electronic media. Officials admit they are pleased with what they see so far, calling it a shining example.

Improving Access in Punjab

The issue of access to resources is particularly critical in places like the rural districts of Pakistan’s Punjab province, where UNESCO and local mobile network operator Mobilink are supporting a literacy project run by the Bunyad Foundation. This award-winning initiative provides girls and young women with cell phones, which are used to link the girls into reading comprehension and discussion forums, all of which takes place through text messages paid for by Mobilink.

“The cell phone holds the key to social development by its very nature and we want to make sure that women are part of this revolution,” says Rashid Khan, president and CEO of Mobilink.

The text messages are delivered in the local Urdu language—implementers learned from previous efforts that English content is neither as accessible nor as engaging.

Indeed, education projects using mobile technologies are evolving quickly and learning from each other all over the globe, as has been the case with the USAID-supported Bridgeit initiative now using mobile technologies to provide educational content to teachers in places like the Philippines and Tanzania.

The Bridgeit program in Tanzania brings together the Tanzanian Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, USAID, Nokia, The Pearson Foundation, and The International Youth Foundation. By providing primary school teachers with cell phones and a rich catalog of educational titles for download, the program offers locally relevant educational videos and other media for schools that would otherwise have extremely limited access to such material.

Thieves and Electricity

There still remain, of course, many challenges to making mobile education projects successful. Concerns over the costs of electricity, costs of network use, and the constant risks of theft and damage to mobile devices are all reasonable threats to project sustainability. In spite of these challenges, tumbling device costs and stronger mobile networks everywhere are two key factors that represent the unprecedented opportunities for public sector leaders, private sector operators, and project implementers to come together and make substantial progress on education in the developing world.

“By exploring appropriate, accessible, and scalable models for mobile technology use in education, we can make profound improvements on the administrative end of the educational process,” says Bloome. “For example, quickly and efficiently tracking student progress and teacher attendance, or using text messages for administrative alerts and updates to improve parental involvement in the educational process would be valuable resources for promoting greater transparency and accountability.”

Many countries across the developing world are also now using mobile technologies to increase and improve communication and monitoring that take place between a school and its local government. This is especially valuable for rural and isolated schools with only one teacher, but also for overcrowded urban schools facing difficulties in monitoring vulnerable children.

“The more projects in this field emerge, the more the possibilities seem endless for using mobile technologies to improve many aspects of the educational process,” says Bloome.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.