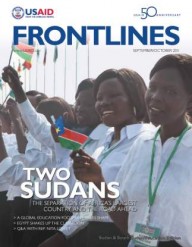

Suzanna Ile and her son Modi at the USAID-supported Lokiliri Primary Healthcare Centre, with the community midwife who helped ensure a safe delivery.

Management Sciences for Health

Suzanna Ile and her son Modi at the USAID-supported Lokiliri Primary Healthcare Centre, with the community midwife who helped ensure a safe delivery.

Management Sciences for Health

Suzanna Ile and her son Modi at the USAID-supported Lokiliri Primary Healthcare Centre, with the community midwife who helped ensure a safe delivery.

Management Sciences for Health

Suzanna Ile and her son Modi at the USAID-supported Lokiliri Primary Healthcare Centre, with the community midwife who helped ensure a safe delivery.

Management Sciences for Health

Suzanna Ile is a 26-year-old woman from Lokiliri Payam in South Sudan. She lost her first two babies in childbirth. During her third pregnancy, a community midwife at the Lokiliri Primary Health Care Centre, a facility supported by USAID, diagnosed her high-risk pregnancy after identifying her contracted pelvis.

Without access to emergency services and a facility capable of performing a Caesarean section, the midwife knew Ile would likely lose her third child as well. A contracted pelvis often results in obstructed labor, fistula, postpartum hemorrhage, or the death of the infant or mother.

Labor complications like Ile’s are common throughout South Sudan, which is one of the world’s most dangerous places to become a mother. With 2,056 maternal deaths per every 100,000 live births, according to the 2006 Sudan Household Health Survey, South Sudan’s maternal mortality ratio is among the highest in the world.

Few pregnant women have access to adequate antenatal care and labor-and-delivery services in the fledgling nation, which represents little change from the years before South Sudan gained independence in July. The single most critical intervention for safe motherhood is ensuring a competent health worker is present at every birth. Yet, many midwives and other maternal and neonatal care providers in South Sudan lack the training required to identify high-risk pregnancies and to perform simple lifesaving procedures at the time of delivery.

The next most critical intervention is the supply of appropriate drugs. Shortages of essential medicines and health supplies are common at South Sudanese health facilities, including drugs for antenatal care and for controlling bleeding during and after delivery. Having emergency obstetric care in place and the transport to get there are the final steps to saving lives. However, in South Sudan, only the most fortunate women are able to reach emergency obstetric care services due to the country’s dearth of good roads and public transportation. Because basic and emergency obstetric care is so lacking, less than one-half of one percent of pregnancies are delivered via Caesarean section—the lowest rate in Africa.

Without skilled birth attendants, life-saving drugs, transportation, or accessible emergency obstetric care, many women have no options if their deliveries become perilous.

Improving Maternal Health Service Delivery

Although decades of civil war badly degraded much of South Sudan’s health care services, efforts in the past six years by the Ministry of Health and its health development partners such as USAID have improved infant and child survival rates.

Even before independence, over the past five years USAID/South Sudan’s health programs concentrated on a small set of high-impact maternal and child health services using simple, cost-effective prevention and treatment measures to counter the most common illnesses or causes of deaths. The high-impact child health services translated into significant gains. The under-5 child mortality rate declined by roughly 22 percent between 2006 and 2010.

Sadly, during the same time period, the best efforts of the South Sudanese public health sector and its partners did not result in the same strides in reducing maternal and newborn mortality, which is defined as death within the first 28 days after birth.

Recognizing this challenge as particularly stubborn, the new Republic of South Sudan has made reducing maternal and neonatal mortality one of its top priorities with a new focus on a basic package of primary health-care services—those that have the highest impact.

Responding to this new focused approach, USAID is partnering with the Ministry of Health and coordinating closely with other health development partners to address the root causes of maternal mortality and newborn deaths. There has been modest progress. By delivering equipment for labor and delivery wards, improving availability of essential antenatal care and maternal health drugs, training health-care providers in detecting high-risk pregnancies and other danger signs, and strengthening the quality of care in health facilities like Lokiliri, USAID is working on behalf of women like Ile to build the capacity of South Sudan’s health system.

“Furthering the recent gains made in child health while addressing the root causes impeding improvement of survival rates of pregnant women and mothers is the top objective of the Health Office of USAID/South Sudan, as it is for the new Republic of South Sudan,” said USAID/South Sudan Senior Health Adviser Pamela Teichman.

One of those impediments is a wary population’s skepticism of such services. In South Sudan, a hospital visit to give birth is an anomaly. Over 85 percent of women deliver their babies at home. And of this great majority, only 10 percent are cared for by skilled health personnel.

“Women’s concerns about quality, cleanliness, lack of privacy and cost of maternal health services are among their reasons for not going to health facilities,” said Cliff Lubitz, USAID/South Sudan’s health team leader. “Lack of transportation is also a huge barrier to obtaining antenatal checkups and emergency obstetric care.”

On the ground, USAID and its partners are working specifically to address women’s concerns. This includes reducing cost concerns by promoting free health services; reducing perceptions of poor service quality by training health-care providers and ensuring drug availability; and mobilizing and educating the community by enabling community leaders and health officials to take the lead in generating demand for more and better health services.

In practice, it works like this: Worried about losing a third baby, Suzanna Ile learns about alternative delivery options during an antenatal care visit to a USAID-trained midwife working at the Lokiliri Centre. Acting on the advice of the midwife, she chooses to deliver by Caesarean section at Juba Teaching and Referral Hospital, and her son, Modi, is now a healthy 2-year-old.

Offering advice to other women in her community, Ile says: “To the ones who prefer delivery on their own, [a hospital delivery] is their chance [for a safe delivery if complications arise].”

USAID/South Sudan now intends to intensify its use of high-impact, low-cost, evidence-based interventions for better maternal, neonatal, and infant health outcomes.

The Agency is joining with the South Sudan Ministry of Health to meet its goal of reducing maternal and under-5 mortality by 20 percent within the first three years of statehood by more aggressively addressing the main killers of mothers and newborns.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.