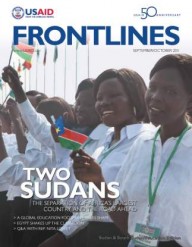

The world welcomed its newest nation when South Sudan officially gained its independence on July 9. After over two decades of war and suffering, a peace agreement between north and south Sudan paved the way for South Sudanese to fulfill their dreams of self-determination. The United States played an important role in helping make this moment possible, and today we remain committed to supporting the people and Government of South Sudan build a peaceful, prosperous nation.

Also on July 9, we opened a full USAID mission in Juba, the capital of South Sudan, to strengthen the progress we have made across the region in partnership with local communities. We have helped provide a million people access to clean water, and financed the construction of roads, bridges, and health clinics. Perhaps most important, we have helped expand school enrollment rates from 25 percent to 68 percent.

A few weeks before South Sudan’s day of independence, I had the opportunity to visit the region and meet a group of children who were learning English and math in a USAID-supported primary education program. The students ranged in ages from 4 to 14. Many of the older students have lived through a period of displacement, violence, and trauma. This was likely the very first opportunity they had to receive even a basic education.

When you see American taxpayer money being effectively used to provide education in a way that improves the lives of these children and contributes to the peaceful founding of a new nation, you get a genuine sense for the significance and long-term impact of this work.

Our goal is to improve equitable access to quality education, particularly in crisis and conflict environments. The challenge is steep. An estimated 70 million children—more than half of whom are girls—are not enrolled in school. Many of those children who do attend school are not achieving basic skills, making it more likely they will eventually drop out.

These failures leave developing nations without the human and social capital needed to advance and sustain development. They deprive too many individuals of the skills they need as productive members of their communities and providers for their families.

Across the world, our education programs emphasize a special focus on disadvantaged groups such as women and girls and those living in remote areas. In rural Liberia—where less than 2 percent of people have electricity—new solar-powered classrooms enable teens and mothers to study at night after finishing a day’s work.

In Afghanistan, we have assisted the government to dramatically expand the number of children enrolled in primary school—from 750,000 boys enrolled under the Taliban in 2001 to approximately 7 million children today, nearly 35 percent of whom are girls.

There is no more powerful tool for creating healthy, prosperous, stable societies than education. We need to continue to seek evidence-based approaches and innovative solutions to providing engaging learning opportunities for the world’s most vulnerable children.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.