The ground serves as a hospital bed at the Koudougou Health Center in Burkina Faso.

The ground serves as a hospital bed at the Koudougou Health Center in Burkina Faso.

The ground serves as a hospital bed at the Koudougou Health Center in Burkina Faso.

The ground serves as a hospital bed at the Koudougou Health Center in Burkina Faso.

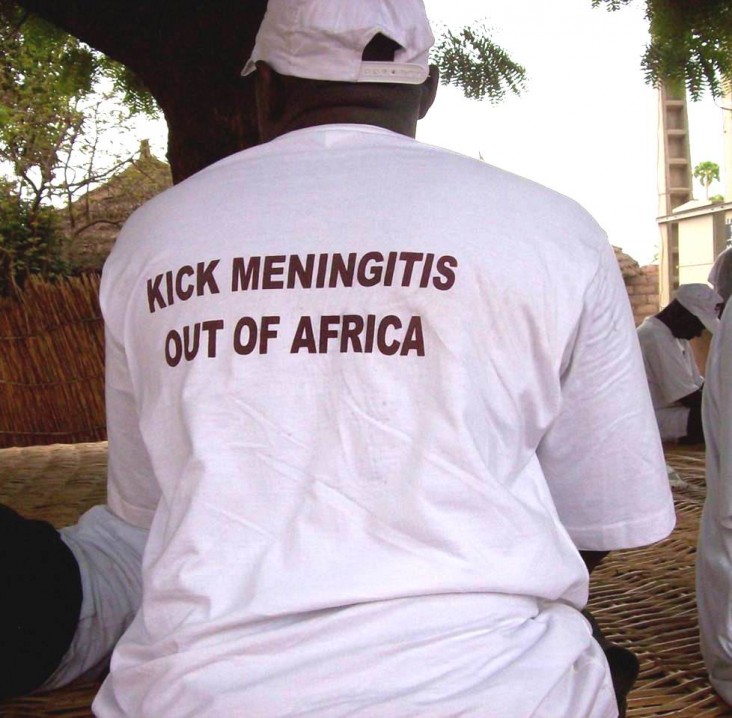

USAID’s Angela Shen interviewed Dr. F. Marc LaForce, an infectious disease physician, epidemiologist and former director of the Meningitis Vaccine Project, on epidemic meningococcal meningitis, a disease that has touched almost every family living in Africa’s meningitis belt. Meningitis epidemics have decimated communities in sub-Saharan Africa for over a century, killing one in 10 people who were sickened and leaving a fourth of survivors severely disabled.

The Meningitis Vaccine Project (MVP), a partnership between PATH, a Seattle-based NGO, and the World Health Organization (WHO) with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, was launched in 2001 following an urgent call from African ministers of health to tackle this problem after the largest meningitis epidemic in African history took 25,000 lives and left many Africans permanently disabled.

By 2004, MVP had succeeded in developing a meningococcal vaccine through a partnership that included the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Serum Institute of India Ltd., an Indian vaccine manufacturer located in Pune, India. African public health officials insisted the cost be kept lower than 50 cents per dose, and the vaccine was introduced in 2010 at 40 cents per dose.

Phase 1 trials began in 2005 in India and then moved to the African continent. After rigorous testing in Africa, the vaccine MenAfriVac was licensed by the drugs controller general of India in December 2008 and prequalified by WHO in June 2010. MenAfriVac was first introduced in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger in 2010 with vaccination campaigns aimed at people between ages 1 and 29. As of March 2014, more than 150 million Africans had received the vaccine, and by 2016, WHO and its partners plan to immunize more than 250 million children and adults in 25 countries. High acceptance of the vaccine is expected to generate “herd immunity” that will protect even those who have not been vaccinated.

Since 2006, USAID has provided $1.2 million for a variety of activities that made development and delivery of the vaccine possible.

FRONTLINES: The first vaccine targeting a disease specific to Africa and one that addresses the longstanding problem of epidemic meningococcal meningitis in sub-Saharan Africa has been introduced. How has vaccination impacted the disease and people’s lives?

DR. F. MARC LAFORCE: After the introduction of MenAfriVac, we have seen a dramatic decline in the incidence of Group A meningococcal meningitis. In fact, incidence rates have fallen to zero in vaccinated countries. The impact on African families has been substantial. Virtually every African family living in the meningitis belt has been touched by this disease, but since the vaccination campaigns, the threat of epidemic meningitis has greatly lessened. This change has led to increased interest on the part of ministries of health in adding other meningitis vaccines such as the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

Both you and I were in Burkina Faso in late February, which in past years would have been in the middle of the meningitis season. This year, nothing was happening, as has been the case since the Men A conjugate vaccine was introduced in 2010. In prior years, the meningitis season, from early January to the first rains in April/May, would have been chaotic weeks, with ministries of health looking for polysaccharide meningococcal vaccines, raising funds for reactive vaccination campaigns while dealing with frightened populations. The contrast was really quite striking.

The important point is that this vaccine will improve African lives through eliminating a vexing and very serious public health problem. However, it is too early to declare a win as the Men A conjugate vaccine has not yet been introduced into the routine EPI [Expanded Program on Immunization] program. The use in the EPI is scheduled to start in 2015, and when that happens, I think that Group A meningococcal epidemics in Africa will be a thing of the past.

FRONTLINES: USAID and others fund surveillance activities for meningitis and other epidemic and vaccine-preventable diseases. Why is surveillance so important to immunization programs?

LAFORCE: One of the key turning points in the Meningitis A story in Burkina Faso was the meningitis surveillance activities that were greatly intensified in 2009, 2010 and 2011. The improved surveillance was possible through major investments on the part of the Burkina Faso MOH [Ministry of Health], the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] and other partners, including USAID. Meningitis is a clinical diagnosis and the proper analysis of spinal fluid specimens from suspect cases is an essential step in order to identify the causative agent. Laboratories need to be well-equipped and transportation systems must be organized to get spinal fluid specimens transferred from the field to qualified laboratories.

In addition, access to new diagnostic techniques is important. Real-time PCR [polymerase chain reaction] was introduced into the Burkina Faso laboratory system in 2010, and proved to be a key improvement in the spinal fluid analyses that were done in 2011 after the Men A conjugate vaccine was introduced. The results were clear: Group A meningococcal disease had virtually disappeared after the introduction of the vaccine. If it weren’t for the improvements in the surveillance activities, we would not have known what happened. The investments in improving surveillance paid a handsome dividend since epidemiologists could accurately study what had happened.

FRONTLINES: MenAfriVac has a unique characteristic; it is stable at room temperature for up to four days. How is this possible given that all other vaccines administered in immunization programs need to be refrigerated? Why is it important?

LAFORCE: Let me answer the second question first. Having access to a vaccine that can be used outside the cold chain dramatically facilitates the logistics in getting immunizations done. One now has a vaccine that can be used in the furthest village first, i.e., it is easier to get vaccine to whoever needs the product. As to the first question, the heat stability of most vaccines has not been well studied. Traditionally, we’ve stored vaccines at 2-8C while we know that certain vaccines like tetanus toxoid are quite heat stable and probably could be safely used outside the usual 2-8C range.

However, vaccine recommendations as to use are quite strict and, once they are established, are unlikely to be changed. Careful studies are needed to show that vaccines are robust enough to be able to persist for an amount of time outside the cold chain. These studies were done with MenAfriVac, and we hope that the example set by MenAfriVac will motivate manufacturers to study the stability of their vaccines so that the Men A conjugate is not a unique product but just one of several vaccines that can be safely used outside the cold chain.

FRONTLINES: As you said, MenAfriVac has had a profound impact on Group A meningococcal disease. What do you see the future of meningitis looking like in Africa?

LAFORCE: I am hopeful that the MenAfriVac success will serve as a clear example of what can be accomplished when a large number of partners focus on getting a public health problem resolved. Granted that there is now persuasive evidence that MenAfriVac has largely eliminated Group A disease in sub-Saharan Africa, we should not lose sight of the fact that there are other meningococcal strains that are circulating in Africa that can cause meningitis.

To date, these strains have not caused the huge outbreaks that Group A meningococci have, but they still cause devastating disease when they occur. Therefore, we are focusing on a follow-on product— a polyvalent meningitis vaccine—that would offer protection against all circulating meningococcal strains in Africa. Broad use of such a vaccine along with Hib and pneumococcal vaccines could offer the possibility that sub-Saharan African would evolve into a meningitis-free area. Wouldn’t that be something?

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.