Lebanese Center for Active Citizenship staff and volunteers march for peace in Tripoli, April 2013. The rally, organized by an NGO coalition, drew 2,500 people. LCAC managed social media outreach on behalf of the coalition.

LCAC

Lebanese Center for Active Citizenship staff and volunteers march for peace in Tripoli, April 2013. The rally, organized by an NGO coalition, drew 2,500 people. LCAC managed social media outreach on behalf of the coalition.

LCAC

Lebanese Center for Active Citizenship staff and volunteers march for peace in Tripoli, April 2013. The rally, organized by an NGO coalition, drew 2,500 people. LCAC managed social media outreach on behalf of the coalition.

LCAC

Lebanese Center for Active Citizenship staff and volunteers march for peace in Tripoli, April 2013. The rally, organized by an NGO coalition, drew 2,500 people. LCAC managed social media outreach on behalf of the coalition.

LCAC

Historically viewed as a bastion of free expression in the Arab world, Lebanon is a country with an intricate media landscape that mirrors the complexity of its politics. Most media outlets are aligned with political parties, covering issues through a narrow political lens rather than a focus on the public interest.

For NGOs, the media environment makes it difficult to advocate solutions to the country’s problems on a non-partisan basis.

“When you have media outlets that tow a certain political line and focus on the activities of politicians and political parties, the voice of citizens gets diluted,” says Roula Mikhael, executive director of the Maharat Foundation, a media watchdog. “As a result, genuine debate on public policies is largely absent from the national discourse.”

Enter social media, which is providing an unfettered space for dialogue. Despite a weak Internet infrastructure, the Lebanese have joined the digital revolution en force.

According to Facebook advertising data, about 1.8 million people—in a country of 4 million inhabitants—are active on the social network. This makes Lebanon one of five Arab countries with the highest rate of Facebook penetration, per the latest Arab Social Media Report by the Dubai School of Government.

This bodes well for NGOs engaged in digital campaigns as it translates into the potential to reach vast numbers of Lebanese men and women rapidly and at low cost.

Taking Local Voices to the National Stage

“The growth of social media has created new opportunities for NGOs to engage citizens,” says Haytham Khalaf, director of the Lebanese Center for Active Citizenship (LCAC).

When LCAC partnered with USAID’s Promoting Active Citizen Engagement (PACE) program in mid-2012, it had a shy online presence. Today, the organization maintains a Facebook page with over 4,400 likers, a blog and the monthly digital magazine The Citizen.

NGO partners like LCAC and others described USAID support as instrumental in helping them exploit digital technologies to foster civic engagement.

“PACE gave us the tools and techniques to make strategic use of social media to advance our goals,” Khalaf says. LCAC uses these platforms to promote the rule of law, equality and public accountability.

“Given the level of political incitement in the mass media, we strive to present these issues in an objective way, from the perspective of citizens. This helps us build credibility with our audience,” Khalaf explains.

Establishing an online presence has also raised LCAC’s visibility beyond local communities. “We’re getting recognized even in remote villages far from our base in Tripoli,” he says.

Despite recurring bouts of violence in the northern city, LCAC managed to train 190 youth on access to information and lobbied decision makers to promote passage of legislation that has been languishing in the parliament since 2009.

In times of crisis, LCAC’s social media skills turned into an important asset for local civic actors. When about 60 organizations came together to plan a peace march in April 2013, LCAC was tasked with social media outreach on behalf of the coalition. Social networks played a critical role in drawing a crowd of about 2,500 people—Sunnis, Christians and Alawites—to call for peace in the troubled city, generating extensive press coverage.

From Elite Circles to Grassroots

While digital tools can help small organizations like LCAC raise local issues to national attention, they are also being used by more established NGOs such as Maharat to expand grassroots reach.

When it partnered with PACE in late 2012, Maharat had virtually no social media presence. It now runs an independent news portal with 38,000 likers on Facebook. Much of the content is developed by journalism students from six Lebanese universities, who earn academic credit for their work.

“Maharat News is a space where up-and-coming journalists can practice what they learn in the classroom in a neutral setting,” says Mikhael. “We cover topics that are often neglected in the traditional media, such as issues faced by youth, women and marginalized groups. Because we’re not affiliated with any political party, we can cover these issues openly, without self-censorship …. We don’t have political considerations, only professional ones.”

Before joining the digital world, Maharat was primarily known in media circles and among decision-making elites given its role in introducing legislation to modernize Lebanon’s antiquated media laws. Going online has allowed the organization to engage youth in the reform debate.

“During our partnership with PACE, we realized the importance of using multiple platforms to get our messages across,” says Mikhael. “We went through internal restructuring to integrate digital technologies in all of our work. We developed a social media strategy, expanded our partnerships with universities, and broadened our circle of stakeholders to reach deeper at the grassroots level and in different parts of the country. It was a major turning point for our organization.”

Influencing Traditional Media

NGOs’ ability to foster debate and galvanize public support via social media is not lost on traditional outlets.

“We as journalists are getting story ideas from social media,” seasoned television reporter Tania Mehanna told civic activists at a media innovations fair organized by PACE in June 2013. The fair brought together over 200 people to discuss increasing convergence across media platforms and leveraged $35,000 in contributions from digital marketing firms.

Participants agreed that social media is a vehicle for social change, but that traditional outlets could not be ignored given their mass appeal. An opinion poll commissioned by PACE in 2013 found that television remains the primary source of information for 90 percent of the Lebanese. The Internet—including news sites, social media and mobile apps—is the second most popular source for 66 percent of the population.

Recognizing the predominance of television, the Lebanese Economic Association (LEA) created a series of video spots about socioeconomic problems such as youth unemployment, the high cost of living, and discrimination against women in the workplace. First released on social media, the series reached 68,000 people via Facebook and YouTube, creating buzz among civic activists and bloggers. LEA then secured free airing for the videos on three TV channels, gaining a rare opportunity to raise awareness of economic policies that have a direct impact on citizens’ lives.

“The videos were produced in a format attractive for television, but it was the solid content that got our messages on the screens and into people’s homes,” says Georgina Manok, LEA project manager.

The young economist describes social media as a “game changer” that has influenced the way NGOs work. “We used to produce technical reports with excellent research and viable solutions to our country’s problems, but few people read them,” admits Manok. Today, LEA relies on multimedia tools such as infographics and animation to simplify complex economic concepts for the layperson.

“We still produce well-researched studies,” she says. “But we’re also reaching beyond economic experts to the average citizen through our blog, Facebook and videos.”

The Online-Offline Nexus

In a country with a history of sectarian conflict and 18 officially recognized sects, the potential of social media to unite citizens around common interests is felt by civic actors such as Nahnoo, a youth-led NGO championing better public space policies. The issue is especially relevant in urban centers such as Beirut, where the average area of greenery per capita is estimated at 0.8 square meters, far below the minimum of 9 square meters recommended by the World Health Organization. The lack of green spaces is compounded by the misappropriation of public areas by private sector interests due to corruption and government inaction.

“To have an impact, however, online activism must complement action on the ground,” says Mohamad Ayoub, the group’s executive director.

In the five years since its founding, Nahnoo has invested in creating a diverse pool of youth volunteers who are trained in leadership and communication skills. “They gained the knowledge to speak with confidence about public space issues,” Ayoub says, adding that the youth helped grow the organization’s reach from its Beirut headquarters to other parts of the country, such as Tyre and Baalbeck. In all three cities, Nahnoo volunteers recently mobilized hundreds of citizens in events aimed at reclaiming neglected public spaces, using online platforms to publicize offline actions.

“If you’re not on social media nowadays, it’s like you don’t exist,” says Ayoub. Nahnoo documents its work on its website, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

“By doing this, we are modeling the transparency we want to see in public decision making,” he explains. “This helps us gain the trust of our online followers. That’s why when we call for action, they answer the call.”

The effective integration of online and offline activism has turned Nahnoo into a reference on public space issues that is frequently cited by traditional media, decision-makers and researchers for its niche expertise.

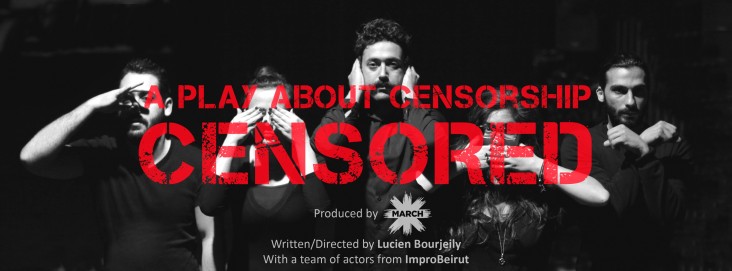

Another young NGO, MARCH, has similarly built a reputation as a resource on censorship issues. With the catchy slogan, “you have the right NOT to remain silent,” MARCH uses bold and thought-provoking messages in its digital campaigns. Its “Virtual Museum of Censorship” documents censored works since the 1940s and its two Facebook pages—MARCH and Stop Cultural Terrorism—grew virally to a combined 24,000 likers, without any paid ads.

The issue of censorship is increasingly resonating with Lebanese youth and free expression advocates due to penalties, arrests and interrogations of several bloggers, journalists and playwrights in recent years. When MARCH teamed up with the Lebanese playwright and theater director Lucien Bourjeily to produce a play about censorship, little did it expect that the play would be banned by government censors or that Bourjeily’s passport would be temporarily confiscated before a trip to London. Social media networks played an important role in mobilizing support for the NGO and Bourjeily, whose passport was returned within 48 hours of the public outcry.

As for the play, whose trailer has attracted over 10,000 views on YouTube, MARCH exploited a legal loophole and was able to perform it on university campuses and generate mass media coverage of censorship issues.

“Ultimately, social media is just a tool,” stresses MARCH President Lea Baroudi. “Inciting people to act is the most important but also most difficult stage of online engagement.”

Realizing this, MARCH networks offline with university students, artists and legal experts to push for reform of Lebanon’s censorship laws and practices. “We’re not just talking online, we’re acting offline too,” says Baroudi. “As a result, decision makers consider us in their decisions. They take us seriously.”

NGOs like MARCH appear to be fighting an uphill battle. The 2014 Media Sustainability Index, which was developed for worldwide use by USAID and assesses media performance in five key areas, gave Lebanon a low score of 1.96 out of 4.0. The country fared even worse, at 1.23 points, when it comes to the extent to which the media serve public needs.

Notwithstanding those rankings, “some TV stations have recently begun to more deliberately give platforms for citizens’ voices,” says Mikhael. “Social media has a lot to do with this. Traditional outlets see that a new generation of Lebanese is heavily engaged on social media. They need to cover the issues that matter to them to keep their audience ratings.”

Ghada Khouri is the chief of party for the Promoting Active Citizen Engagement program.

Mobile Technologies As Citizen Reporting Tools

Tripoli, Lebanon’s second-largest city, is generally viewed as a barometer of sectarian relations in the country. When political tensions run high, Tripoli is often the first area to explode into violence between gunmen from Bab El Tebbaneh, where most residents are Sunni, and Jabal Mohsen, inhabited mainly by Alawites.

Ironically, the rival neighborhoods have much in common. They both suffer from high rates of poverty, youth unemployment and weak public infrastructure. Lack of opportunities and development initiatives fuels frustrations and mistrust of government, especially among youth.

Working with three Tripoli-based NGOs, the Association for Development in Akkar (ADA) seeks to change that through social media, local publications, community outreach and a mobile app to prompt citizens to report problems related to the quality of public services.

Trained youth groups follow up on the complaints with the municipality, which has pledged collaboration and joined the project’s steering committee. ADA President Ali Omar hopes that tangible results from the project, which began in September 2013, will motivate youth to direct their energies toward improving their communities.

While it may appear that mobile apps are out of reach in impoverished areas, many Lebanese youth have access to used smart phones, sold at a fraction of their original price. Countrywide, smart phone penetration rose from 36 percent to 63 percent between 2012 and 2013, according to market research firm IPSOS-STAT, and the rate is likely to increase further this year.

Other NGOs are capitalizing on this trend. The League of Independent Activists (IndyACT) recently launched the first civil society news app in Lebanon. The app is populated by civic activists around the country and submissions are verified by IndyACT.

ITvism developed an online platform to track traffic violations and poor road conditions. Dubbed “Kamashtak” (Lebanese slang for “I caught you”), the platform has documented 13,000 cases, which are reported by trained fieldworkers and regular citizens via online and mobile submissions. The Kamashtak team is using the data to advocate solutions to public authorities and plans to expand the platform to tackle other citizen concerns.

All of these initiatives, supported by USAID through the PACE program, are ongoing and their long-term impact is too early to gauge. What is clear, however, is that digital tools have unleashed local creativity in tackling persistent problems in new ways.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.