A worker fills a bag of rice at a processing plant in Temeye, Senegal. Liberalization of the country’s rice sector, with USAID support, has been a boon for the country’s domestic production.

Stephane Tourné, USAID

A worker fills a bag of rice at a processing plant in Temeye, Senegal. Liberalization of the country’s rice sector, with USAID support, has been a boon for the country’s domestic production.

Stephane Tourné, USAID

A worker fills a bag of rice at a processing plant in Temeye, Senegal. Liberalization of the country’s rice sector, with USAID support, has been a boon for the country’s domestic production.

Stephane Tourné, USAID

A worker fills a bag of rice at a processing plant in Temeye, Senegal. Liberalization of the country’s rice sector, with USAID support, has been a boon for the country’s domestic production.

Stephane Tourné, USAID

DAKAR—Twenty years ago this January, the entire West African region was on its way to an economic calamity. The main currency in the region, the African Financial Community franc, or CFA, lost half its value almost overnight, effectively doubling the price of anything anyone wanted to buy – from a loaf of bread to a pair of shoes.

In Senegal, the surprise devaluation of the CFA was particularly devastating to a banking sector already teetering near collapse. But there was a silver lining to the financial fall. The crisis compelled the Senegal Government, which had been working with USAID on banking reforms for several years, to fast-track regulations that loosened longstanding state-imposed price controls.

The move saved the nation’s economy.

In fact, wholesale reforms of both the banking sector and the rice import industry led to a burgeoning of the private sector and free markets. That, in turn, led to improvements in the overall economy, helping the country reduce the extreme poverty wrought by years of economic near-paralysis.

“Senegal was facing almost total stagnation in the financial sector,” said Mamadou Lamine Loum, a former prime minister and finance minister at the time of the economic collapse. “Donors were insisting on reform, and though painful in the short term, the devaluation enabled us to put a new liberalized system in place that exists to this day.”

The key, Loum said, was enacting new microfinance policies that facilitated access to credit for small-scale rural farmers, opening the door for small loans that dramatically increased farmers’ earning power, leading to across-the-board increases in the country’s standard of living. (See sidebar below.)

Loum said assistance from USAID in drafting the legal framework for the reforms led to an “explosion” of more than 2,000 microfinance institutions that provided financial help to small businesses and farmers.

“In the early 1990s, USAID was a pioneer in microfinance development in Senegal and the entire West Africa region,” said Loum. “The model we created here was replicated in nearly every other country in the regional monetary union.”

Liberalizing the Rice Market

Prior to USAID’s intervention, Senegal’s rice sector was dependent on price controls and central planning of rice distribution under a government agency that controlled rice imports. To keep local supply high, it set high prices on wholesale and retail rice to limit imports. It didn’t work.

By the early 1990s, the system had become bloated and inefficient, causing massive rice shortages and exorbitant costs that affected the quality of nutrition as well as household income across the nation. With the CFA franc devaluation, prices of the staple grain—a part of almost all major national dishes—doubled, threatening the food security of the country’s rural population.

In 1994, at the Senegalese Government’s request, USAID launched a five-year, $30 million rice sector adjustment program to help alleviate the systemic inefficiencies in the rice market, while providing the financing necessary to help the government bear the costs. To liberalize the rice market, the new program promoted competition among private sector importers. This change brought consumer prices down and increased incomes of domestic rice farmers, which improved food security for their families. Sixty-five percent of Senegal’s economy is based on agriculture.

The agencies that had controlled rice prices were gradually phased out, replaced by small, private wholesale distribution markets.

A new rice marketing information system followed in 1997. This system provided information on domestic pricing to customers and all rice market participants, and a new, crucial element of transparency to the market. Rice prices were now determined by supply and demand, while processing, importing and distribution were entirely in the hands of the private sector, ultimately reducing prices and improving incomes for rural producers, processors and distributers.

“The project was an outstanding success,” said Ndiobo Diene, secretary general of the Ministry of Agriculture and a key player in the project’s implementation. “We made remarkable progress in achieving all our operational policy reform objectives ahead of schedule. By 1999, the rice sector was privatized, liberalized and functioning smoothly.”

Today, about 20 firms account for most rice imports, and competition among importers is rigorous enough to ensure downward pressure on prices. Elimination of subsidies has encouraged many farmers to vary their crops and branch out into other areas of agriculture, such as cereals, vegetables and peanuts.

Misguided Banking Policies

As a precursor to the rice reforms, USAID assisted Senegal to consolidate its banking system to make it more profitable, and encourage savings and credit institutions to provide financing and loans to small enterprises and smallholders, including women.

In the mid-1980s, Senegal’s banking sector consisted of 15 commercial banks and seven non-bank financial institutions, dominated largely by French-owned institutions. The system was plagued by low profitability and poor management, resulting in a portfolio of bad debts. The government would routinely interfere in bank management via misguided economic policies, often to meet political objectives, which eroded confidence as debt soared.

More important, these problems took place among an elite urban community, not the vast majority of Senegal’s population, who had no access to any of these funds that could help them get ahead economically.

In 1987, a donor-funded wholesale review of the sector determined that six out of the 15 major banks were in danger of bankruptcy. Failed bank loans totaling $840 million represented 60 percent of total credit to the economy and 17 percent of GDP. Senegal teetered on the verge of financial catastrophe.

“A Critical Role”

Two years later, USAID’s $35 million in bilateral support—more than any other donor—helped the Central Bank of West African States adopt comprehensive reforms that re-established confidence in foreign lenders and resulted in $312 million in refinancing mechanisms. The World Bank provided $45 million.

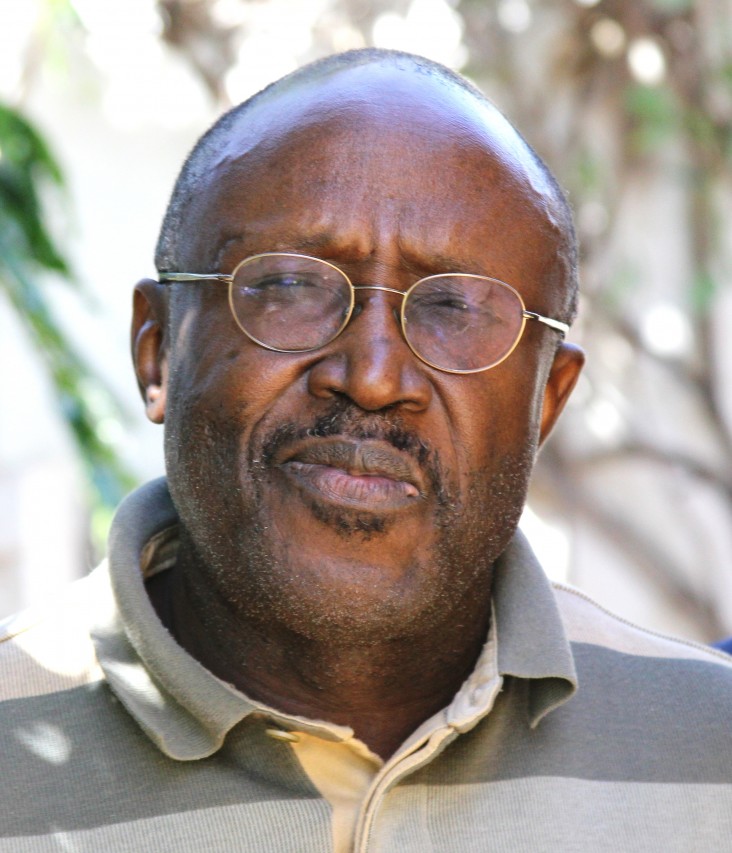

USAID played a critical role in a banking reform process launched in early 1990 known as the African Economic Policy Reform Program, said Ousmane Sané, USAID’s resident economist since 1984 who was deeply involved in the reform process.

“That decade [1995-2005] represented the highest rate of economic growth and poverty reduction in Senegal’s history,” Sané said. “Banking sector reform, especially the emergence of microfinance led by USAID, along with liberalization of the rice sector has led to a decade of rising prosperity. As a result, extreme poverty dropped by 36 percent.”

According to the World Bank, the rate of poverty—the number of individuals earning $1.25 a day or less—stood at 66 percent in 1990 and 30 percent in 2010. The number of people in Senegal who accessed microfinance rose steadily—to 450,000 in 2002, shooting up to 1.6 million in 2005, according to the International Monetary Fund.

In November 1999, USAID launched a new five-year, $26.5 million project called DynaEnterprise to improve access to financial services and increase use of managerial best practices among micro, small and medium enterprises. Ultimately, the project was able to cover 91 percent of the microfinance market.

“I reflect on our work led by USAID as a great success,” said former Central Bank of West African States Director Seyni Ndiaye, “as part of an amalgamated donors group who urged that management must be driven less from the administration and more towards the marketplace.”

As a result of these successful USAID interventions, Senegal has become arguably the most financially stable country in West Africa.

The increased stability engendered by reform projects in the banking and rice sectors has highlighted USAID’s abilities in financial and sectorial restructuring and has influence policy reform in other parts of Senegal’s economy over the years through assistance in other areas, allowing this dynamic nation to reach its full growth potential, Sané explained.

For the moment, however, Senegalese are appreciative of USAID’s past help, as well as its results.

“This was very important to the development of rural agriculture,” Ndiaye said, in speaking about rice sector reforms. “Twenty years later, the system remains solid. It played a key role in anchoring an emerging economy.”

Loans Pull Farmers from Poverty

By Rose Kane

Since 2002, Anna Gaye has been a member of a 600-member farmer organization that stretches across 52 villages in the rural community of Mampatim in the conflict-affected region of Casamance in southern Senegal.

For years, most members of the group called Kissal Patim—two-thirds of them women—cultivated small garden patches near village wells that produced off-season vegetables for market. Others had access to larger, half-acre rice plots that yielded perhaps 200 kilograms during the rainy season.

They earned small amounts of money each week, and divided up a larger amount among members once a year. But over the past four years, membership has surged to 1,000, and Kissal Patim is able to cultivate and process surplus rice.

Since 2010, with assistance from USAID, Kissal Patim has been able to access credit. Each member receives about $200 per year. With these funds, the women have invested in small-scale mills, which allow them to process rice plants into flour for sale much more efficiently, freeing them from the toil of the traditional mortar-and-pestle. The organization has become a fully registered seed producer, part of a network that reaches about 1,000 farmers who produce rice for consumption and sale.

“Our plots have grown fourfold,” Gaye said. “We can now cultivate up to an entire hectare, each of which yields an average of four and a half tons. In the future, we hope to manage even larger plots to feed our families and sell rice to townspeople.”

Through its Economic Growth Project, USAID promotes the high-yielding New Rice for Africa, known as NERICA.

“The new NERICA rice varieties can produce yields as much as three times greater than what they used to get, while needing less water,” Gaye said.

With credit, this group and others have been able to purchase mechanized seeders and modern tilling implements that bring still better yields.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.