Miean Keng and her grandchildren, ready for school

University Research Co. LLC

Miean Keng and her grandchildren, ready for school

University Research Co. LLC

Miean Keng and her grandchildren, ready for school

University Research Co. LLC

Miean Keng and her grandchildren, ready for school

University Research Co. LLC

While Cambodia has made tremendous strides in reducing poverty—dropping from 50 percent to 20 percent between 2004 and 2011—much of the population still hovers just above the poverty line where they remain highly vulnerable to slipping back into poverty.

Health care is just one indicator. It is expensive, and nationwide 70 percent of the total spent on health care is paid out-of-pocket. There is also a growing body of evidence that links illness and access to health care with debt, sale of assets and poverty.

USAID has been working with the Cambodian Ministry of Health and partnering with Australia’s aid agency, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and the U.K. Department for International Development on an insurance program known as the Health Equity Fund (HEF) to provide poor households with free access to public health services. This system currently enables 21 percent of the country’s population to meet basic health needs, helping them to overcome a basic hurdle to moving out of extreme poverty—improving their health.

“While overall incomes in Cambodia are rising, there remains a large portion of the country that is vulnerable to health shocks,” said USAID/Cambodia Mission Director Rebecca Black. “These shocks could force families to borrow money at higher rates, sell their assets and push them deeper into poverty. USAID has been pleased to support the Cambodian Government in its commitment to reduce poverty, and the Health Equity Funds have shown real results in this area.”

Fewer households are falling into debt to pay for health care. Two recent surveys show that household debt for health care has fallen across the country, but that effect is more pronounced in areas where HEFs provide support. HEFs reduced out-of-pocket expenditures by the poor on health care by 29 percent and reduced the amount of their health-related debt by a quarter.

Approximately 3.1 million poor Cambodians are now enrolled in the HEF. The poor are identified by local government authorities through routine interviews that take into account household assets and vulnerabilities. Those identified are provided with a free “equity card” that grants them access to all services available at public health facilities. When members of poor households are hospitalized, they are also provided with reimbursement for transportation and a food allowance of $1.25 per day for the patient’s caretaker.

Soy Neart and her husband, Chorn Pharn, say their family is enjoying better health today thanks to their enrollment in the HEF in 2009. The couple was living in a 12 foot by 16 foot thatch house in the rural province of Kampong Cham with their daughter, who suffered what seemed like endless rounds of severe pneumonia. Looking back, Neart is convinced that indoor cooking over an open fire in the poorly ventilated thatch home was the cause of many of her daughter’s lung infections.

With each new lung infection, Neart and her husband, fearing for their daughter’s life, took her to the local hospital. Each visit cost between $15 and $25 and required them to spend a few nights with her in the hospital while she received IV fluids and antibiotics. To pay for her treatment, they bought less food and took on additional debt. As a result, they were forced to depend on their neighbors for financial support.

After the couple enrolled in the HEF, they started to receive medical treatment from the local government health center and hospital without charge. This enabled them to seek preventive health care before a situation became urgent, which improved their health and allowed them to work more. In turn, they began to pay off debts and save for a new house.

After three years of saving, partially due to the HEF, they have built a new and better home, which is much better ventilated. The smoke from indoor cooking no longer threatens to give children in the house lung infections as it did before.

“Now, I’m very happy that my family has good health. I have more time to earn and save for my family than I did before. If I didn’t have the Health Equity Fund, I would have more debt and would have had no chance of building a suitable house,” said Neart.

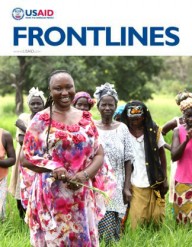

Another insurance convert is Miean Keng, a 55-year old widow in Phnom Penh who lives in a rented house with her 10 children and grandchildren. Her monthly salary of $25 working as a cleaner, along with the earnings of two of her children, pays for rent and schooling. But there was nothing left for medical expenses.

In 2010, Keng was identified as poor by local authorities and signed up for the benefits under the HEF. Without it, they would have either foregone treatment or taken on debt. After the death of her husband in 2004 from a gall bladder infection, Keng worried about not having money for health care treatment when a family member fell ill.

“We love our HEF card … it is like cash in hand when we are sick” said Keng. “With my current situation, it is very hard to borrow money without land or a house as collateral. The HEF has helped us with health care and our economic situation. With only $75 in total income a month to support our family, not having medical costs means I can buy food, keep my grandchildren in school, and pay the rent and utilities.”

Since 2003, USAID provided direct support to the HEF system and, by 2013, had gradually handed over direct financing of the system to the Ministry of Health and pooled donors. This year, the Government of Cambodia is funding 40 percent of the HEF system, with the other 60 percent coming from a pool of donors. USAID now provides only technical assistance to ensure the program operates effectively.

Political support for the system is high, with the prime minister calling for scale-up of HEFs nationwide. The Ministry of Health has made this insurance and quality control scheme a key component of the national health strategic plan.

Eng Huot, secretary of state for the Ministry of Health, noted in 2010 that “By using Health Equity Funds, the Ministry of Health has helped more than 70 percent of people who are living under the poverty line to obtain access to health-care services at public health facilities.”

The HEF model’s reputation is spreading beyond Cambodia’s health ministry. The Ministry of Education has indicated that it, too, plans to review how the model could be applied to education.

Tapley Jordanwood is with University Research Co. LLC, and serves as the chief of party for the USAID Social Health Protection Project.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.