A young fisherman in Timor-Leste

USAID CTSP/Matthew Abbot

A young fisherman in Timor-Leste

USAID CTSP/Matthew Abbot

A young fisherman in Timor-Leste

USAID CTSP/Matthew Abbot

A young fisherman in Timor-Leste

USAID CTSP/Matthew Abbot

It happens every day all across the country. People swing by the local grocery store to pick up some tuna fillets or frozen scallops for a quick and tasty seafood dinner. Chances are that tuna and scallops came from a vast expanse of marine and coral ecosystem in the Asia-Pacific called the Coral Triangle.

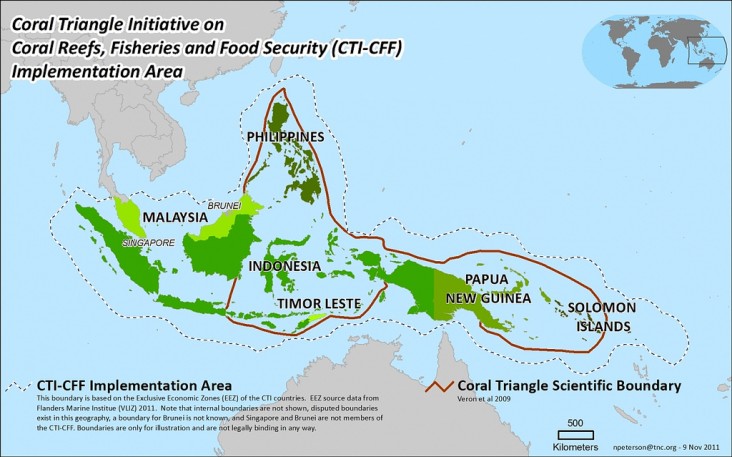

Forming a rough triangular shape that encompasses Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Solomon Islands and Timor-Leste, this area half the size of the United States is home to the world’s largest concentration of marine life, including several endangered species of tuna. The Coral Triangle is known as the Amazon of the Seas because, like the Amazon rainforest, it is rich in biodiversity, with over 600 species of corals or three-quarters of the world’s known coral species, and over a third of the world’s 2,500 species of reef fish living under its waters. It is also a critical spawning and nursery ground for six of the world’s seven species of marine turtles and endangered marine life such as southern bluefin tuna and blue whales.

This marine treasure, however, is at risk. A report by the World Resources Institute released in 2012 showed that as much as 90 percent of the reefs in the Coral Triangle are threatened by overfishing, population growth, development, pollution and the impacts of climate change. Weak governance and limited law enforcement resources combined with increasing demand for seafood make sustainable management of this underwater ecosystem a huge challenge.

The problems facing the Coral Triangle are also set to negatively impact the 363 million people living inside its boundaries, 130 million of whom are directly dependent on its resources for their livelihoods and food security. Many of them earn a little more than a few dollars a day.

The area is also a major supplier to global markets, sourcing more than 20 percent of the total global fisheries supply, as well as to the United States, which imports a whopping 91 percent of the seafood consumed by Americans every year. Several Coral Triangle countries, like Indonesia and the Philippines, export the majority of shrimp, scallops and clams available on the U.S. market. Indonesia alone contributed about a quarter—or about 13,000 tons—of the fresh and frozen tuna imported by the United States in 2010, a catch valued at $112 million.

The marine scientist who first mapped the Coral Triangle, J.E.N. “Charlie” Veron, maintains that it is the global epicenter for marine life and must be protected. “The degradation of the Coral Triangle is so great that we must hurry to preserve the best of it,” he said in 2009.

Conserving a Way of Life

Beginning around 2004, families living in Barangay Bacao on the Philippine island of Dumaran, who relied on the live reef fish trade for their livelihoods, knew they had a big problem on their hands.

Extensive illegal fishing and destructive fishing practices were decimating the coral reefs and the reef fish they needed for their trade, but they did not know the extent of the damage or what they could do to improve their situation.

In 2011, a coral reef assessment revealed the alarming rate of depletion of the corals and fish stocks in Dumaran. The assessment, facilitated by the World Wildlife Fund through the U.S. Coral Triangle Initiative Support Program (USCTI), called for the establishment of more marine protected areas (MPAs), no-take zones for spawning sites, and mixed-use sites for general subsistence fishing. Spearheaded by USAID, the USCTI was established by the U.S. Government in 2008 to assist the leadership of the Coral Triangle countries in taking action to maintain this unique marine treasure.

The poor state of the local marine resources also motivated the local government to be even more aggressive in enforcing existing MPAs as well as expanding their numbers.

“Illegal fishing activities have decreased, especially dynamite and compressor methods. [Our] mayor is very strict,” says Edgardo Paguntalan, president of Bacao’s Barangay Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Management Council (BFARMC).

Without competition from the illegal fishers, the small fishermen in Dumaran have been able to reap their share of the bounty of the sea and improve the quality of their lives.

Jesus Peañar, a fisherman and small live fish trader, is now building a kitchen extension for his house in Barangay Bacao. He recently installed a well at his property; acquired a new, more powerful motor for his fishing boat; and paid his fishing and caging license fees.

“It has been great to see a natural balance restored in the local reefs,” said Paguntalan. “We have seen what can happen when steps are not taken to protect the environment, and we want fishing to be a viable way of life for our children.”

Paguntalan himself has enjoyed success in the live reef fish trade. Not only was he able to build his modern concrete house, he was also able to expand his family-run store and increase inventory from everyday consumer needs to livestock feeds and gasoline for motorboats.

Following an information and educational campaign conducted by WWF, local residents are actively cooperating in government-led conservation efforts. Marine protected areas will increase from 37 hectares to 16,648 hectares (0.14 square miles to 64 square miles), a development that will surely benefit future generations of Dumaran fishermen.

Supporting a Cutting-Edge Regional Marine Governance Initiative

Just as the coastal and island communities of the Philippines are changing their ways to conserve their marine resources, so are policy makers. In 2007, Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono began talking about conserving and sustaining the Coral Triangle, the waters of which link the six countries within its bounds. He invited the leaders of the other five Coral Triangle countries to join him in his campaign and they agreed, launching the Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries and Food Security (CTI-CFF).

With its strong history of engagement around marine issues, USAID recognized the potential for a regional agreement to strengthen marine resource governance and conservation. Within months, the Department of State, USAID in Washington and its Regional Development Mission for Asia, as well as its missions in the Philippines, Timor-Leste and Indonesia, put in place the multi-part USCTI in September 2008. The initiative brought together the technical expertise and local knowledge of a consortium of NGOs, including the World Wildlife Fund, The Nature Conservancy, and Conservation International—which together make up the Coral Triangle Support Partnership, a key implementer of the project—as well as the scientific expertise of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and access to a deep pool of technical experts to work with local organizations and policy makers.

Of the contributions by U.S. scientific experts, a NOAA-supported fish biomass study provided critical information on the health of fish stocks in Timor-Leste’s waters that is informing government decision making.

Timor-Leste Secretary of State for Fisheries and Aquaculture Rafael Gonçalves recently acknowledged the benefits of the study. “Before, we did not know about the state of our reefs, their importance and the level of threats. Now we have an understanding of this in certain areas,” he said.

With USCTI support, the Coral Triangle nations moved quickly. In May 2009, the six nations formally established the Coral Triangle Initiative for Coral Reefs, Fisheries and Food Security (CTI-CFF) by signing a Declaration and Regional Plan of Action. Each member country followed with its own national action plan to coordinate activities and policy within and across national boundaries.

Five years after the official launch of the USCTI, a regional system of ocean governance is in place that is transforming the region. Through U.S. support:

- Nearly 10,000 government, NGO and community representatives from the Coral Triangle have been trained in natural resources management;

- Nearly 20 communities in five countries are managing their local marine resources;

- Nearly 20 million hectares (nearly 76,000 square miles, or almost the size of South Dakota) of biologically significant areas as well as coastal and marine areas are under improved management;

- And 93 policies, regulations, laws and agreements contributing to coastal and marine resource management have been developed.

“This support is contributing towards making the protection and conservation of the biological diversity of a unique region of our planet a reality,” Timor-Leste President Taur Matan Ruak said about the regional effort in July 2013.

Jane Lubchenco, former head of NOAA, has called the Coral Triangle Initiative a “beacon of hope” in sustaining marine resources and “the broadest and deepest engagement in regional ocean governance to date.”

USAID continues to play a role in moving momentum forward by providing ongoing financial and technical support in collaboration with other donors.

The six Coral Triangle nations have started a region-wide effort to protect the food security, well-being and economic potential of the most productive ocean area in the world. The building blocks for achieving long-term results have been laid with achievement of key regional actions, which included the development of regional plans to manage fisheries, the creation of marine protected areas, and an action plan and guide for climate change adaptation.

Communities in all six countries have begun to feel the positive impact the initiative has had in their daily lives, such as the families in the Philippines. The impact will be sustained once the initiative completes institutionalization through establishment of a permanent regional secretariat.

The Tasks Ahead

Over five years, the Coral Triangle countries have worked together to manage their shared, invaluable ocean equities, despite differences in national capacity and resources. The six Coral Triangle countries speak more than 1,000 languages between them and have varying forms of government, economies, development challenges, and marine and coastal resource management issues.

According to Sudirman Saad of Indonesia, chairman of the interim regional secretariat of the Coral Triangle Initiative for Coral Reefs, Fisheries and Food Security (CTI-CFF), regional initiatives are by their nature challenging, and the CTI is no exception. However, he says, “the CTI-CFF has demonstrated that by working and collaborating at the regional, national and community level and involving as many stakeholders in our programs, the initiative has made headways in protecting our marine resources.”

USAID support and partnership with the Coral Triangle nations has opened a new chapter in sustainable management of the most biodiverse and productive ocean region in the world. Locals across the region are beginning to understand that conservation makes good business sense, too.

Six hours away from Timor-Leste’s capital in the eastern village of Vailo Viai, Robella Da Cruz has operated a guest house for more than a decade. Her business is now within sight of a “no-take” zone that villagers and staff from the Coral Triangle Support Partnership established to help fish stocks replenish.

The project has engaged the local women’s group, led by Da Cruz, to provide valuable information about conservation issues that can impact local household economics, helping to reinforce sustainable fishing practices with their husbands and children.

Da Cruz, whose business success largely depends on preserving the pristine ecosystem, is helping others in her community understand that marine conservation and economic growth are not mutually exclusive. When she recently saw a green turtle laying eggs in the sand near her guest house, she realized that few eggs would survive long enough to hatch due to the many pigs that scour the beach for food. She quickly erected a simple fence around the site using fishing nets, and although the pigs got a few eggs, at least 60 hatchlings made it to the sea under Da Cruza’s watchful care.

When asked about it, she simply smiled and said it “just makes good business sense.”

This article was written by staff from the U.S. Coral Triangle Initiative Support Program and the USAID Regional Development Mission for Asia.

Indonesia: When Science and Tradition Combine

Nusa Penida, and its neighboring Indonesian islands, Lembongan and Ceningan, are fishing islands located near Bali. However, the islands’ marine resources were threatened by overfishing and destructive fishing practices such as the use of explosives and cyanide or bleach, which either kill outright, or stun large numbers of fish for collection. These techniques indiscriminately kill all sea life in the target area and can demolish fragile coral reefs. In support of the goals of the Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries and Food Security, the USCTI team conducted pioneering underwater surveys and numerous consultations with communities to develop a program to protect the islands from overfishing and at the same time encourage eco-tourism.

Using local knowledge and cutting-edge science, the 20,000-hectare (50,000-acre) Nusa Penida marine protected area was established in 2010 and has since helped stabilize reef and fisheries conditions and eliminated the use of destructive fishing methods. “Villagers have been happy to see science and tradition combined for effective zoning and resource use,” said I Wayan Supartawan, one of the island’s leaders.

Papua New Guinea: Coastal Communities Take Action to Adapt to Rising Seas

Three neighboring villages on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea affected by coastal erosion and salt intrusion in their backyards and water sources are facing the impacts of climate change using the framework and tools developed by the Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries and Food Security and the USCTI. After noticing considerable rise in sea water levels in their area, the villagers sought the help of the USCTI team, which helped them draft a climate change adaptation plan. As a result, the villagers planted mangroves along the water and new crops on higher ground. Neighboring villages are also paying attention and have developed similar strategies.

“We saw the damage to the shore and big erosion taking place. We saw the effects of climate change, so we decided to get along with the process for the good of future generations,” said Francis Tapo, deputy chairman of the Londra Community Organization on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea.

Solomon Islands: App Helps Fisheries Gather Data

To fill the gap in fisheries data collection in the Solomon Islands, the USCTI came up with a mobile platform that sends data from 28 landing centers in nine provinces to a central server housed and managed by the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources (MFMR) in Honiara, the country’s capital. The project, being implemented in partnership with Solomon Islands Telekom, is the first coordinated initiative to gather inshore fisheries data in the country, and will help the government address overfishing, declining fish stocks, reduced catch, potential impacts of climate change on inshore fisheries and overall food security.

“For fisheries management and to support fishing communities, we need accurate data on production, species, origin and by whom inshore fish are being caught,” said Ben Buga, marketing director and chief fisheries officer at the MFMR. In March 2013, the program was cited as an exemplary public-private partnership that supports and promotes conservation and sustainability during the third Coral Triangle regional business forum. The program provides a model for other Coral Triangle and Pacific countries on how to use existing technology for sustainable local economies and food security.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.