Saiga males during mating season in open field

Igor Shpilenok

Saiga males during mating season in open field

Igor Shpilenok

Saiga males during mating season in open field

Igor Shpilenok

Saiga males during mating season in open field

Igor Shpilenok

At the farthest outreaches of the world, modern problems that affect us all are impacting once isolated and untouched landscapes. Problems such as wildlife trafficking, which undermines security and fuels organized crime, as well as urbanization and infrastructure development, which puts increased pressure on biodiversity and natural resources, are becoming familiar topics of conversation at dinner tables around the world from Alaska to Aktobe, Kazakhstan.

On a faraway Asian plateau between the Aral and Caspian Seas in a temperate desert shared by Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, these two problems have come to a head, and the locally revered saiga antelope—a cultural symbol comparable to the cherished bald eagle in the United States—is paying the steep price.

The Ustyurt Plateau is one of the last remaining critical habitats for the saiga, and it is also one where the saiga faces an immediate risk of extinction. Since 2009, the Ustyurt Plateau’s saiga population has been cut in half—to less than 5,500. This species of antelope has experienced one of the most sudden and massive declines of any mammal, with a 95 percent reduction in population over the last 20 years. Once a population of more than 1 million, this critically endangered species now numbers roughly 200,000 in just four countries—Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Russia.

The saiga’s decline is largely fueled by high demand for their horns and meat. Substances contained in saiga male horns are used in traditional medicine in China, where they fetch up to $100 per kilogram (2.2 pounds). This September, border police in northwest China seized 35 boxes containing thousands of antelope horns valued at $22 million.

Illegal trade in saiga horns contributes to increased corruption and undermines rule of law, a fact underscored by President Barack Obama’s signing in July of a new Executive Order against wildlife trafficking to better coordinate the U.S. response to “an international crisis that continues to escalate,” because “the survival of protected wildlife species … has beneficial economic, social and environmental impacts that are important to all nations.”

Another driver of the saiga’s decline is the development of infrastructure on the plateau, such as rail lines and border fences, which interrupt migratory patterns, cause disturbances to habitat, and increase injuries. These threats stem from the development of extensive natural gas and oil deposits under the Ustyurt. Without sensitive planning, the extraction and associated infrastructure development could cause large-scale degradation of the Ustyurt landscape.

To conserve the vital Ustyurt Plateau habitat for the saiga and to help curb its illegal trafficking, USAID and its partners are leading key interventions through the Ustyurt Landscape Conservation Initiative (ULCI).

Tackling the Decline of the Saiga: A Multifaceted Approach

Launched in 2009, USAID’s five-year initiative is promoting the long-term sustainable management of the Ustyurt landscape through a multifaceted approach involving various international partners. ULCI is part of USAID’s flagship global conservation program called SCAPES: Sustainable Conservation Approaches in Priority Ecosystems.

The initiative is implemented by a consortium of partners led by Washington, D.C.-based Pact Inc., in partnership with U.K.-based Fauna & Flora International, the oldest international conservation organization in the world. Two Kazakh entities play a crucial role in the project’s success: the Forestry and Hunting Committee under the Ministry of Environmental Protection of the Republic of Kazakhstan, and the Association for the Conservation of Biodiversity of Kazakhstan, a non-profit conservation organization.

The initiative includes improving anti-poaching efforts as well as promoting education and awareness about the saiga and the Ustyurt’s fragile desert ecosystem.

To fight poaching, the consortium partnered with the Kazakhstan Customs Control Committee and sponsored training for its workers to use sniffer dogs to help detect illegally traded antelope horns. The effort started this year and is expected to significantly improve the detection of cross-border smuggling of antelope horns. In addition, the project has been supporting and training rangers in the Ustyurt Plateau.

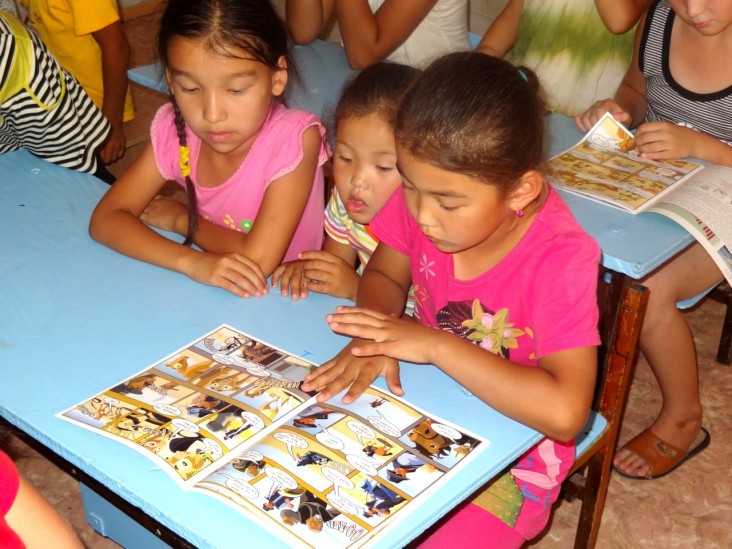

To help raise awareness and galvanize widespread public and governmental support for saving the saiga from extinction, the initiative launched a multimedia campaign that included print, radio and online ads to educate the public on existing laws that prohibit hunting or trading saiga. Short public service announcements were displayed in public spaces. Billboards sponsored by the local government were put up throughout the Ustyurt region, and posters were displayed at a railway station and airport. Comic books called “The Saga of the Saiga,” also featured prominently in the campaign.

These public relations efforts have paid off, according to Paul Cowles, ULCI program manager for Pact. “Government officials have shown a greater interest in and knowledge of saiga antelopes after we aired the TV spots and distributed posters,” he said.

Following in Their Footsteps: Mitigating Infrastructure Impacts

USAID is also working to raise awareness of the impact of infrastructure on saiga migratory patterns. The Ustyurt saiga migrate across the border from Kazakhstan to Uzbekistan during harsh winter conditions and return again in spring, but recently constructed border fences and railways have created additional barriers that interrupt important migration routes, cause disturbance to habitat and increase chances for injuries.

ULCI partners worked with the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, an intergovernmental treaty backed by the United Nations Environmental Program, and the Frankfurt Zoological Society, a nonprofit international conservation organization based in Germany, to co-finance a study on maintaining habitat for saiga in Kazakhstan.

The resulting report, published in 2013, included proposed modifications to railroads and border fences and was widely distributed among government authorities and NGOs specializing in environmental issues.

“The initial response from the border agencies was very positive,” said Maria Karlstetter, former program manager at Fauna & Flora International. “There was a general willingness to take the bottom wire off the border fence where it crosses saiga habitat on the Ustyurt Plateau, which would allow saiga to cross without harm.”

Overall, there has been some progress in attaining a better outlook for the saiga. According to a June 2013 report by the Kazakh Government, saiga numbers in Kazakhstan have more than doubled compared to five years ago, thanks to better coordinated efforts between the last four remaining saiga habitat countries—Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Mongolia and Russia. But much more needs to be done to ensure that this unique animal remains on the planet for future generations.

“While the situation is improving, concerted efforts need to be taken from all angles to achieve long-term success for the saiga,” said USAID’s Diane Russell, who manages USAID funding for ULCI. “There are many factors to be considered to understand what approaches are most effective in increasing the saiga population. Part of USAID’s role since 2009 has been to help improve knowledge of the situation, and contribute to the development of better informed conservation strategies.”

Unintended Consequences of Losing the Saiga

If the saiga disappear from the Ustyurt Plateau, it will be more than just the loss of one of the most important cultural icons to the people of Kazakhstan. Not only will it have an impact on local livelihoods, it will have implications for other species one day as well. A lack of cyclic grazing and fertilization by the saiga antelope is thought to impact the spread and diversity of vegetation. Maintaining vegetation is important for local herders whose livelihoods depend on a healthy Ustyurt landscape.

Additionally, saiga serve as food for predatory animals like raptors. Thirty different reptiles and amphibians, 45 mammals and 50 species of birds coexist on this land.

“Life on the planet is supported by a web of biodiversity, which includes unique species like the saiga antelope. Its role as a grazer is critical to maintaining the vegetation for the unique ecology of the area and local herders,” said USAID’s Mary Melnyk, environment and agriculture team leader. “We in the United States are fascinated by what seem to be oddities in nature and the different types of animals the world presents. The saiga has a snout of a moose, but horns like antelopes and lives in the faraway place of Kazakhstan, the site of invasions by Genghis Khan and the famed Silk Road.”

Saving the saiga on the Ustyurt Plateau is all the more important as the threat of desertification looms on the horizon.

“The landscape itself, which is vast, is at risk from a changing climate,” said Russell. “According to a group of experts, the general trend in the Ustyurt is warming, both in terms of fewer cold days in winter and increased number of hotter days in summer. … Saiga play a key role in maintaining the integrity of the landscape.”

Through an ecological youth club that USAID helped establish, the next generation is beginning to show a greater interest in conserving their environment.

“We are learning more about animals and plants, the environmental situation of the region, and how to preserve and protect the ecological foundation of our native land,” said Gulsezim Elubaeva, a biology teacher at Shalkar city school in the Aktobe region. “With the help of the project, I developed a course on the animals of Ustyurt. The course familiarizes children with the local environment and wildlife. It also helps them understand the importance of environmental preservation.”

Kirk Olson, formerly of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and now field manager for ULCI, concentrates on the urgency of conservation efforts.

“The future of the saiga as an iconic symbol of endless and intact steppe will be decided in the coming decade,” he said. “Will they be included in Kazakhstan’s future, or will they be left behind?”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.