Conserving forests for wildlife does not mean local inhabitants have to lose out. USAID-supported programs in western Tanzania have demonstrated that when communities participate and have ownership over the planning and management of vital natural resources, positive attitudes and conservation behavior follow.

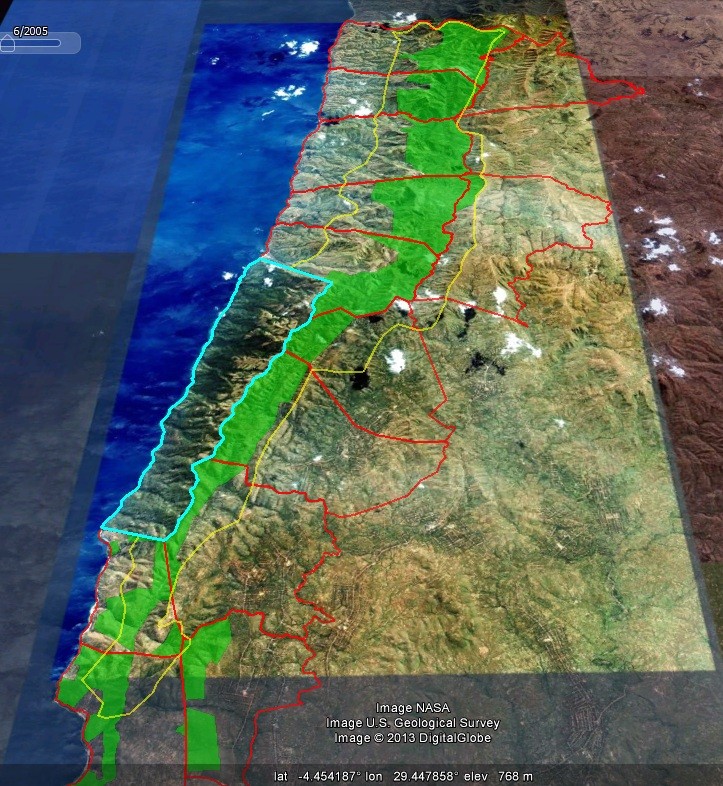

The Gombe-Masito-Ugalla (GMU) ecosystem, which includes Gombe National Park where world-renowned primatologist Jane Goodall conducted her seminal research on wild chimpanzees, covers an area roughly the size of Connecticut. With assistance from the Jane Goodall Institute, a USAID partner, 49 villages in the GMU have created their own land use plans and placed 726 square miles of land under improved land management. Inhabitants are now practicing agroforestry and engaging in environmentally sustainable livelihoods that reduce deforestation and pressures on their natural resources.

“Agroforestry that was introduced by the program has helped people double and triple yields from the same piece of land,” notes Gilbert Kajuna with USAID/Tanzania’s natural resource management team.

The GMU ecosystem, which is bordered by Lake Tanganyika on the west and Burundi in the north, is made up of predominantly Miombo forests. The forests provide a habitat for 25 percent to 40 percent of Tanzania’s chimpanzee population, as well as significant populations of other primates and threatened species such as elephants. The forests are also a source of medicines, fuel, food, fibers and construction materials that support the livelihoods of 311,000 people in the GMU.

The villages’ land use plans include forest reserves that are protected from human activity and encroachment. As a result, there is now a swath of protected forest running north to south adjacent to the Gombe Stream National Park. This contiguous conservation area covers almost 50 square miles and provides a corridor and buffer zone for chimpanzees and other wildlife in and around Gombe National Park.

“A major achievement of the program has been to mitigate the conflict between humans and wildlife in the GMU while helping the communities manage their natural resources for long-term benefits, but this has not always been the case,” remarks Kajuna.

Over the past 35 years, the forests of the GMU, as in other parts of Tanzania, have experienced an alarming rate of depletion and degradation, seriously threatening wildlife and the livelihoods of people living in the area.

In the 1970s, the Tanzanian Government’s collectivization policies relocated rural inhabitants from scattered settlements into clustered, communal villages. In 1972 and again between 1996 and 1997, the country received an influx of refugees fleeing conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi. These two factors, plus local population growth, increased the population density of the GMU by nearly 50 percent.

This put severe pressure on the natural resources as the increased number of inhabitants cleared land for new farms, and harvested the forest’s trees for firewood and to build houses and fishing boats. The extensive loss of forest vegetation resulted in landslides, choked lakes with silt, diminished wildlife habitats and threatened important watersheds with destruction.

In the early 1990s, when Goodall flew over the area she had worked in for decades, she was shocked to see the rapid pace of deforestation in the Gombe area. Where the rate of deforestation had been 214 acres per year before 1991, it doubled to 422 acres per year by 2003 and over 65 percent of the chimpanzee habitat around the Gombe was lost.

Repeated surveys between the mid-1960s and the mid-2000s show that during this time, the chimpanzee populations outside the National Parks decreased approximately 44 percent. Goodall realized that only by addressing the realities of the people living around the Gombe would it be possible to conserve the habitat of the chimpanzees.

In 1994, the Jane Goodall Institute embarked on a community-centered conservation approach through the Lake Tanganyika Catchment, Reforestation and Education Project, which has since expanded into the Gombe-Masito-Ugalla program.

“Initially, the activities focused on tree planting, but people didn’t adopt it. Forest degradation was not a priority for them,” says Emmanuel Mtiti, program director of the Gombe-Masito-Ugalla program. “There was a lot of distrust of conservation activities because people were afraid of losing their land as they had when the government decreed the Gombe area a national park in 1968.”

In 2003, with assistance from USAID, the Jane Goodall Institute embarked on an integrated program in the GMU that introduced communities to sustainable agricultural techniques such as agro-forestry. Harvestable trees like the fast-growing calliandra are grown among crops, helping to preserve the soil so farmers can continue to till the same land instead of clearing forests for new land. Calliandra trees—known locally as moto mwaka (fire within a year)—supply a renewable and local source of firewood for cooking and reduce the need to harvest firewood where chimpanzees and other wildlife thrive.

The USAID-supported program also helped local residents earn incomes in new areas, such as establishing tree nurseries and woodlots that produce trees with specific uses for food, medicine, timber and agro-forestry.

Local farmer Bonaventura Luzilo, who received training from the program and started a tree nursery in 2002, now raises 25,000 tree seedlings per year. He sells seedlings to other villagers, and he grows trees in his woodlot for construction and firewood. With his new income, Luzilo has been able to send his children to school, and build a new house for his own family and one for his aging mother.

“I really thank the program for changing my life and giving me a future,” says Luzilo. “I am proud to be a conservationist … I think I am making a difference to other people’s lives as well since they have established woodlots with the seedlings they bought from my nursery. And sometimes I gave some seedlings free. The seedlings have grown to become big trees.”

To date, the program has helped establish 464 woodlots and 77 tree farms in 35 villages.

What the Next Generations Reap

The program also targeted the next generation of ecosystem stewards through environmental education for youth. Initially, this was an extracurricular activity, but more recently grew to include environmental education training for teachers so they could fold what they had learned into classroom instruction. Between 2010 and 2013, the program trained about 280 teachers from 48 schools, reaching more than 12,400 students. One of the program’s objectives is to work with the Ministry of Education to include environmental education in the curriculum of all Tanzanian schools.

Seeing the positive impact that the program was having on the communities in the GMU, USAID partnered with the Jane Goodall Institute in 2005 to implement an expanded program. While building on existing activities that promoted agro-forestry and increased household incomes from the sustainable use of natural resources, the next phase also aimed to increase the amount of land under conservation through community-led land use planning and management.

It took some convincing for some communities to participate.

“When the village land use planning was initially introduced to our village in 2009, my community was divided. There was resistance from some people in the village that did not accept the idea in fear of a rumor that our land would be taken away as part of a plan to expand Gombe National Park,” explains Hussein Kasalla, chairperson of Kigalye village.

Kasalla’s own family, residents of the GMU for three generations, had experienced such displacement in the past. “My grandparents moved into Gombe forest in 1937 and settled at the site known as Mitumba, which is now the headquarters of Gombe National Park. My father was born in Gombe. We were then asked by the government to move out of the forest but we were resistant to move, so our houses were burned down and we were forced to move out,” he says.

In order to sensitize the villages to the land management concept, the Jane Goodall Institute took village and religious leaders on field trips to other more severely impacted districts to observe and hear firsthand how lack of land use planning and deforestation caused erosion, depleted soil productivity and diminished natural watersheds.

“We faced floods that demolished one of the classrooms at our primary school so we thought we should stop some of the activities that caused floods,” says Kashindi Msafiri, a Kigalye resident. “We were convinced, after being educated by the Jane Goodall Institute staff, that some of our problems were due to forest degradation.”

The sensitization meetings and field trips helped convince village chairperson Kasalla that the land would not be taken away. “We learned from neighboring villages that had accepted and implemented land use planning that they were in a better position to manage their land and yet they still kept their land,” he says.

To ensure that the land use planning was a participatory and truly community-owned process, the communities selected a village land use management team from community members who were not village leaders.

“The team had to be presented to the whole village assembly for approval. The condition was to have at least one woman representing each hamlet on the team,” recounts Kasalla.

Every village’s land use plan includes residential areas, land to be used for sustainable farming and agro-forestry, and conservation areas such as village forest reserves and watersheds. Land use plans also include by-laws and sanctions for managing and protecting the land.

Program Director Mtiti describes the typical scenario for creating land use plans: “The village management teams lay out their plans by creating a simple diorama on the ground using sticks, stones and leaves to mark out different land use areas in the plan.” District surveyors then come to the village and use GPS to digitize the simple diorama plan, which the Jane Goodall Institute overlays with DigitalGlobe satellite images and develops a map. The map is presented to and endorsed by the village in a general assembly.

The District Council collects the village plans and by-laws, which are sent to the Ministry of Natural Resources for signing. “This ensures that the by-laws are legal and protected by the courts,” says Mtiti.

The program also helped the villages to select and train 61 volunteer forest monitors to manage and patrol the village forest reserves. The monitors collect and report information on human activities in the reserves, such as farming and tree cutting, as well as incidents of wild fire. The monitors also record wildlife sightings including chimpanzee nest counts and tree measurements.

In addition, the monitors are equipped and trained on the use of Android smartphones and tablets to collect and upload data into the Google cloud where it can be stored and shared. To date, the program has distributed 30 Android phones and 10 tablets for data collection. Google has donated an additional 1,000 tablets to the Jane Goodall Institute, 200 of which will be distributed to community volunteers and program staff in Western Tanzania.

“This was my first time to get involved in conservation,” says Kashindi Msafiri, a forest monitor from Kigalye village. “I attended training organized by the Jane Goodall Institute and I am later joining Pasiansi Wildlife Training Institute for a three-month training.”

As a result of the USAID program, local inhabitants are now controlling, managing and protecting their own natural resources and the forests in the GMU are regenerating. According to Gabriel Batulaine, senior environmental specialist for USAID/Tanzania, “Now the chimps have an expanded area to move into and the locals are spotting chimps in places that they haven’t been seen for more than a decade.” Current research also suggests that the chimp population in the GMU, that was declining 10 years ago, is stabilized.

Kasalla notes that it is because of the program that “we have peace of mind when we go to sleep during the rainy season. Our school, that was gradually being eroded from flooding, is now stable. We are now working toward controlling illegal hunting. We are now seeing wildlife and birds coming back. We are proud because this is all from our success.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.