Laurence Chandy and Homi Kharas

Can extreme poverty be ended by 2030—and if so, what will it take?

This audacious question posed by the architects of the post-2015 Development Agenda soon will be enshrined in a set of sustainable development goals. Answers—and progress toward these goals—begin in understanding extreme poverty’s “last mile.”

The past quarter-century has been a period of undoubted progress in the fight against extreme poverty. The first Millennium Development Goal aimed to halve the global poverty rate, based on the frugal $1.25 poverty line, between 1990 and 2015. This goal was met five years ahead of schedule; the global poverty rate fell from 43.0 percent in 1990 to 20.6 percent in 2010.

To end extreme poverty by 2030, this same rate of progress—a reduction of one percentage point per year—must be sustained. Expressed this way, the goal seems reasonable. One might even conclude that it represents a baseline scenario for the future, since it requires no deviation from the global poverty rate’s historical trajectory.

Instead, two competing narratives have emerged on the future pace of global poverty reduction.

The first narrative assumes that the speed of poverty reduction is bound to slow. The reduction in global poverty since 1990 has been driven by spectacular performances in countries such as China, Indonesia and Vietnam. The success and scale of poverty reduction in these nations compensated for countries that recorded little or no progress. Such divergent outcomes were sufficient for meeting the goal to halve global poverty, but they will not deliver on a zero-poverty goal.

For this to happen, each developing country must individually be on a trajectory to end poverty by 2030—a significant deviation from the historical path for many countries.

We have identified 21 countries1 with both elevated poverty rates and poor records of progress over the past decade. All face one or more structural challenges to inclusive growth: they are small or land-locked, have bad neighbors, are disaster- or disease- prone or have a record of bad governance or conflict. Such countries are gradually coming to dominate the composition of the world’s remaining poor. The share of the global poor living in fragile states has doubled, from 21 percent to 42 percent, since 1990.

Getting to zero poverty by 2030 requires that each of these countries defies its circumstances and, in some cases, match or better the fastest recorded poverty reduction trajectories from history.

Yet in practice, it’s hard to simply throw off the legacy of structural challenges to development. Weather shocks—which are expected to grow in frequency due to climate change—have been found to have persistent effects on the welfare of the poor. For instance, even 10 years after droughts in Ethiopia and Tanzania in the 1990s, the consumption levels of poor households remained 17 to 40 percent below their pre-disaster levels.2 Structural factors can also interact to disastrous effect. Drought in Syria and the internal migration it precipitated have been linked with the start of the country’s civil war.3 A decade ago, only 1 percent of Syrians lived below the extreme poverty line. According to today’s best estimates, this fraction has risen to 31 percent—higher than the poverty rate in Ethiopia.

Even those countries that are on a trajectory to zero can expect to face headwinds between now and 2030. Because concentrations of people are typically thinner at the ends of the income spectrum, countrywide gains in income typically deliver less poverty reduction once poverty numbers reach low levels.

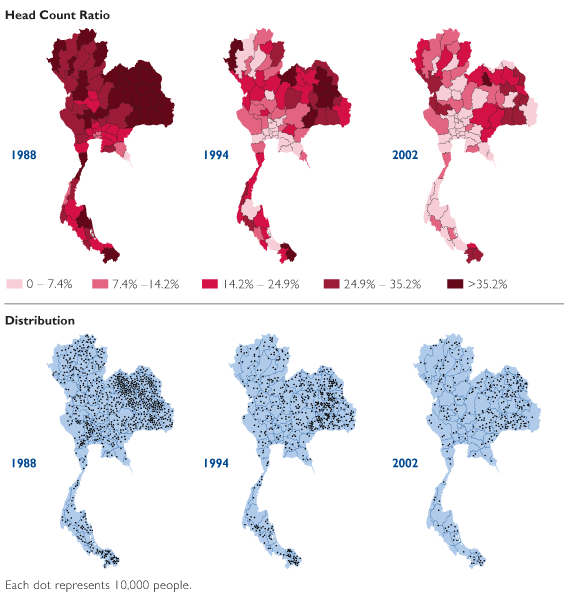

The emergence of persistent pockets of poverty in lagging subnational regions, or among selected population groups, is also cause for concern. These pockets may result from market and local governance failures or discrimination and exclusion. Thailand represents one example. Despite the country’s success in bringing down its poverty rate from 17.2 percent in 1988 to less than 5 percent by 1994, residual pockets of extreme poverty still existed in the northeast region of the country eight years later (Figure 1). This continues to the present.

Looking across the record of developing countries over the past three decades, there is some evidence that the rate of poverty reduction is slow in countries where the poverty rate is in single digits.4 Supporters of this narrative conclude that the last mile in ending extreme poverty will be the hardest, both within individual countries and globally, prompting some analysts to describe the 2030 goal as “very challenging,”5 “unrealistic”6 and “out of reach.”7

The emergence of persistent pockets of poverty in lagging subnational regions, or among selected population groups, is also cause for concern.

There is a counternarrative to this prognosis, however, that is equally compelling and grounded in empirics, in which national and international efforts successfully overturn decelerating pressures on poverty reduction. In this second narrative, as the number of people living in extreme poverty falls, the fight against poverty will change in form and grow in effectiveness. As countries get richer and the scale of global poverty declines, the level of resources per poor person that can be deployed to reduce extreme poverty will rise.

Efforts to tackle poverty could then shift from scattershot approaches to more targeted interventions tailored to individual needs and circumstances. New technologies in identification, communication, payment, digitization and data processing could make such targeted efforts increasingly feasible by reducing transaction costs, minimizing leakages and generating audit trails.

Meanwhile, the introduction of more rigorous evaluation methods for development programming can help identify transformative interventions that generate large and sustained increases in income for poor households. A leading example is cash transfers, which are among the most thoroughly researched interventions in global development.

Cash transfers have been shown to deliver annual monetary rates of return between 20 to 80 percent, sustained over several years.

Though encouraging, such microeconomic evidence historically has been considered to be of limited relevance for understanding poverty trends across the developing world. The reason for this: Poverty-focused programs and their impact rarely scale successfully.

But this, too, is beginning to change. Technology and evidence—the same factors driving efficiency gains in development efforts—are also laying the groundwork for better scaling. And since the number of people remaining in extreme poverty is falling, our notion of what constitutes “scale” is becoming more attainable, because it involves reaching a declining number of people.

The spread of cash transfers alongside other kinds of social safety nets exemplifies this shift. In 2010, an estimated 50 million people saw their incomes raised above $1.25 a day as a direct result of all such transfers.8

An additional 345 million people living on incomes under $1.25 a day benefited from these transfers but did not receive enough to rise above the poverty line. As the number of extremely poor people falls and the number of poor beneficiaries rises, it is tempting to speculate a time when safety nets lift all people remaining in extreme poverty above the $1.25 threshold.

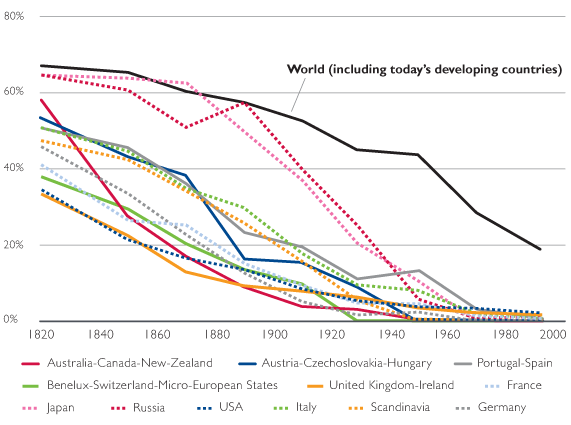

Above all, this counternarrative hinges on effective policy-making. It requires both a dedicated effort to tackle poverty and efficiently designed and executed interventions. This is precisely what gave today’s rich countries the ability to eliminate extreme poverty in the middle of the 20th century.9

This era marked the development of many of today’s most important social programs, such as Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps and the Earned Income Tax Credit in the United States. Countries like Japan, Russia and Belgium saw little slowdown in their rates of poverty reduction as extreme poverty approached zero, as Figure 2 illustrates.

Whether extreme poverty is eliminated by 2030 ultimately depends on which of these two narratives proves dominant. The challenge for the global development community is to reconcile, and draw insights from, both perspectives.

The “diminishing returns” trajectory serves as a reminder that the international community must do a far better job of helping conflict- and climate-affected countries and the need for inclusive growth strategies that promote education, job creation and mobility. The “accelerating to zero” narrative stresses the importance of effectively mobilizing and allocating resources in support of poverty-reducing programs and developing tools to strengthen the resilience of poor households.

While the future trajectory of global poverty is virtually impossible to predict, our understanding of what it takes to eliminate poverty is growing. The global community now must seize this knowledge, so that the dream of a poverty-free world becomes reality.

Laurence Chandy is a fellow in the Global Economy and Development Program and the Development Assistance and Governance Initiative at The Brookings Institution.

Homi Kharas is a senior fellow and deputy director for the Global Economy and Development Program at The Brookings Institution. The views expressed in this essay are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

1 Benin, Burundi, Central African Republic, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Mauritania, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nigeria, North Korea, Papua New Guinea, Somalia, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

2 Beegle, Kathleen, Rajeev H. Dehejia and Roberta Gatti. “Child Labor and Agricultural Shocks.” Journal of Development Economics 81: 80- 96. 2006. http://users.nber.org/~rdehejia/papers/childlabor_shocks.pdf

3 Werrell, Caitlin E., and Francesco Femia eds. “The Arab Spring and Climate Change.” http://climateandsecurity.files.wordpress.com/2012/04/climatechangearabs...

4 Ravallion, Martin. “Benchmarking Global Poverty Reduction.” The World Bank: 2-33. 2012. http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/1813-9450-6205

5 Yoshida, Nobu, Hiroki Uematsu and Carlos E. Sobrado. “Is Extreme Poverty Going to End?” The World Bank:1-27. 2014. http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/IW3P/IB/2...

6 Bluhm, Richard, Denis De Crombrugghe and Adam Szirmai. “Poor trends: the pace of poverty reduction after the Millennium Development Agenda.” UNU-MERIT: 1-28. 2014. http://www10.iadb.org/intal/intalcdi/PE/2014/13584.pdf

7 Ncube, Mthuli, Zuzana Brixiova and Zorobabel Bicab. “Can Dreams Come True? Eliminating Extreme Poverty in Africa by 2030.” Institute for the Study of Labor: 1-25. 2014. http://ftp.iza.org/dp8120.pdf

8 The State of Safety Nets 2014. Rep. no. 1. The World Bank. 2014. http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2...

9 Ravallion, Martin. “The Idea of Antipoverty Policy.” National Bureau of Economic Research: 1-113. 2013. http://www.nber.org/papers/w19210

Frontiers in Development

Section 1: Understanding Extreme Poverty

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.