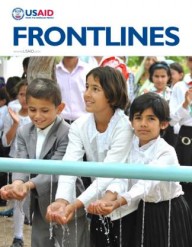

Children wash their hands in Ghana, where USAID supports prevention and treatment of trachoma, a blinding eye disease.

International Trachoma Initiative (ITI)

Children wash their hands in Ghana, where USAID supports prevention and treatment of trachoma, a blinding eye disease.

International Trachoma Initiative (ITI)

Children wash their hands in Ghana, where USAID supports prevention and treatment of trachoma, a blinding eye disease.

International Trachoma Initiative (ITI)

Children wash their hands in Ghana, where USAID supports prevention and treatment of trachoma, a blinding eye disease.

International Trachoma Initiative (ITI)

It’s 8 p.m. on a hot Sunday evening in July in Tinabelle, a tiny village in northwestern Ghana. A small group of men and women sit together listening to a public radio program about how communities can protect themselves against trachoma, a blinding eye infection.

Trachoma is a devastating disease that spreads from person to person through contact with bacteria-carrying flies, which feed on discharge around peoples’ eyes and noses. As the program, produced by the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation and funded by the multi-donor International Trachoma Initiative (ITI), ends, the group launches into an animated discussion about the disease-preventing strategies presented on the radio show—reducing the fly population by keeping the village clean; fixing broken latrines and burying excrement; and washing children’s faces and hands to keep them free from flies and the bacteria they carry.

The group members gather once a week to listen because they know it is helping to keep trachoma at bay in their community. As active members of the village’s radio listening club, it’s their job to motivate their neighbors to be vigilant about personal hygiene and to make sure that the latrines and borehole wells that were destroyed during the rainy season are fixed.

Radio programs, trainings and other community education efforts are helping groups like this one make important changes in their communities. Among the initiatives they’ve helped implement, with support from their village chief, is getting everyone in the community to participate in mandatory communal cleaning every Friday.

“The trachoma radio programs have made the village healthier,” said Abdulai Debrah*. “Before, you could see filth all around, children’s faces dirty and flies everywhere.”

The Trouble with Trachoma

Until just a few years ago, trachoma was a serious public health problem in Ghana. A decade ago, the disease was endemic in all 29 districts in the Northern and Upper West regions, putting over 3 million people at risk. In five districts, the infection rate among children was over 10 percent in 2003; and nationwide, about 6,000 people had trichiasis, the most advanced and extremely painful late stage of trachoma, and were awaiting surgery to repair their inverted eyelids and stop their eyelashes from scarring their eyes. Without this surgery, they would likely go blind.

According to Simon Bush, director of advocacy and African alliances at Sightsavers, the constant pain of trichiasis blindness can have a particularly devastating effect on the livelihoods of people living in developing countries.

“There is often little support available to people living with disabilities in the developing world,” he says. “They and their families have little chance of ending the cycle that keeps them in poverty, which is why tangible solutions to curing and preventing disability are so important.”

While Ghana’s task—safeguarding its at-risk citizens from trachoma—was daunting, the small West African country was far from alone in its fight against this highly preventable disease. In 1985, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that worldwide, up to 360 million people in 55 countries across Africa, Asia, Central and South America, Asia and the Middle East were at risk for contracting the disease.

In 1998, WHO ramped up efforts to fight the disease, calling for its worldwide elimination by 2020. The resolution helped focus the world’s attention on the issue; and in Ghana, it helped the Ministry of Health begin to enlist the support it needed from international partners to start fighting the disease in earnest.

The trachoma elimination program began in 2001, following disease mapping. After conducting baseline surveys in suspected endemic areas, the partnership, led by the Ghana Health Service, started making plans to implement the gold standard strategy for fighting trachoma, known by the acronym SAFE.

The SAFE Way

SAFE is a four-part prevention and treatment strategy endorsed by WHO for fighting trachoma. The four letters stand for surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness and environmental improvements. People who have trichiasis are treated with corrective surgery. Antibiotics serve two purposes: treating trachoma infections before they develop into trichiasis, and preventing disease transmission when given to entire communities on an annual basis over a five-year period. Facial cleanliness and regular hand-washing are effective ways to prevent disease transmission. Environmental improvements, such as improved access to water and sanitation facilities, are also important for prevention. Without access to clean water, families cannot wash their hands and faces, keep their communities clean, or reduce local fly populations.

“As straightforward as the SAFE strategy sounds, a significant rollout of all components of SAFE is urgently needed in countries suffering from trachoma,” says Angela Weaver, senior adviser for USAID’s NTD program. “This requires the active engagement and ownership of affected communities, effective leadership from endemic countries, dedicated donors and implementing partners, strong global coordination, and increased resources.”

Dr. Uche Amazigo, former director of the Africa Program for Onchocerciasis Control, agrees. “The donors bring the funding …; the communities provide the human resources that you need to distribute the drugs; the NGOs train these human resources and collect the drugs [donated by pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer, Merck and GlaxoSmithKline] from the port of entry and bring them to the nearest health post for the communities to collect and distribute,” she says.

USAID has supported Ghana’s efforts to curtail NTDs, including trachoma, since 2007, focusing on activities associated with mass drug administration (MDA) for disease prevention, including disease mapping and surveillance, training for MDA-related activities, and drug distribution. With USAID funding, the Ministry of Health mapped 170 districts for soil-transmitted helminths and schistosomiasis. Almost 150,000 drug distributors, supervisors and trainers have been trained in MDA-related activities. Perhaps most important, USAID has funded preventive drug treatments for millions of people each year. In 2012, some 24 million people were treated for one or more NTDs.

“Since USAID’s NTD program was launched in 2006, our priorities for trachoma have included mapping the distribution of the disease by district in order to obtain Zithromax® donated by Pfizer Inc., and on supporting a massive scale-up of drug distribution to communities at-risk. Over the coming years, impact surveys and post-treatment surveillance will be high priorities as we assist countries on the path to WHO certification of elimination,” says USAID’s Weaver.

Ghana: 1, Trachoma: 0

Ghana’s national NTD program has already begun to see some signs of success. In 2010, after seven years of consecutive SAFE strategy implementation in all 29 endemic districts, and with support by USAID, END in Africa and numerous other partners, health officials were able to halt MDA campaigns for trachoma in the endemic districts, although drug treatments are still administered in seven small communities that need them.

“Ghana is at the verge of trachoma elimination,” said Dr. Nana Kwadwo Biritwum, Ghana’s Neglected Tropical Disease program manager, at a September 2012 meeting of NTD control supporters on Capitol Hill.

“Trachoma is the largest infectious cause of blindness in the world,” says Weaver. “To put that in better perspective—the disease blinds roughly four people in the world every hour. The results are not only devastating to individuals who suffer from blindness, but also to their families and communities. These are families living in some of the poorest and most vulnerable parts of the world, and this disease only perpetuates a continuous cycle of poverty.

“However, I do believe we have reached a tipping point with this disease. With a highly collaborative community of partners, for the first time ever, we have the opportunity to make significant progress toward the goal of elimination by 2020.”

Since 2011, Ghana has done surveillance in all 29 previously endemic districts to ensure that the disease has not returned; and health officials in the country cautiously confirm that trachoma transmission has been broken. With that victory, Ghana became the first sub-Saharan African country to reach the SAFE strategy’s goals of reducing the prevalence of blinding trachoma to less than 5 percent at the district level and to stop the disease as a public health problem.

For people in Ghana, this accomplishment has meant a life without constant pain or disability. Adwa Ama*, a single mother and trichiasis surgery patient, said that before the procedure she “felt like tiny pins were piercing my eyes, even when I tried to sleep. Now [after the surgery], I don’t have pain in my eyes anymore and I can earn money to buy food for my children.”

*Real name withheld for privacy reasons.

Katherine Sanchez is with FHI 360.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.