Farm attendant Rhoan Hepburn, rear, with fourth and fifth grade students in the breakfast feeding program at the Flanker Primary and Junior High School. Here they pose with the crops they reaped from their farm, located on the school’s grounds.

Kimberley Weller, USAID

Farm attendant Rhoan Hepburn, rear, with fourth and fifth grade students in the breakfast feeding program at the Flanker Primary and Junior High School. Here they pose with the crops they reaped from their farm, located on the school’s grounds.

Kimberley Weller, USAID

Farm attendant Rhoan Hepburn, rear, with fourth and fifth grade students in the breakfast feeding program at the Flanker Primary and Junior High School. Here they pose with the crops they reaped from their farm, located on the school’s grounds.

Kimberley Weller, USAID

Farm attendant Rhoan Hepburn, rear, with fourth and fifth grade students in the breakfast feeding program at the Flanker Primary and Junior High School. Here they pose with the crops they reaped from their farm, located on the school’s grounds.

Kimberley Weller, USAID

In 2007, Flanker, a squatter community within Jamaica’s St. James parish, was labeled the most violent place in the country and believed to be beyond redemption. Infested with guns and gunmen, no police dared enter.

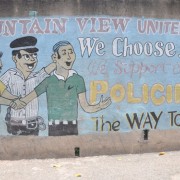

That began to change as residents and law enforcement allied to combat crime and violence with U.S. assistance. In 2008, USAID began work in Flanker through the Community Empowerment and Transformation (COMET) project. USAID strengthened local organizations such as the Flanker Peace and Justice Center and supported community-based policing to increase trust and cooperation between members of the community and the police.

In addition, in 2011, the U.S. Department of Defense assigned its Jamaica-based civil affairs team, or CAT, to work with USAID and the Jamaica Constabulary Force to detect, disrupt and defuse criminal organizations within certain communities, including Flanker, and to help build safer communities within the country’s most volatile areas.

“It’s all about the police. We support the police to work more with community members. This then creates greater trust between the two groups, which leads to a legitimacy to report crimes. Hence, reductions in violence,” explained the CAT team leader, Capt. Paul Meyers.

Flanker residents give some of the credit for their more peaceful streets and improved relationship with police to this effort, which has been maintained by local community groups and the community-based policing program.

Makeda Williams, president of the Flanker Community Action Development Committee, has been a resident of the community all her life. “There has been a vast improvement between the community and police, but there is still a need for improvement,” she says. “It is known that the community is still somewhat armed, and our police learned how to navigate throughout the lanes during times of violence. We want to see more police conduct foot patrol because our conflict resolution is not fully sorted out. It is a work in progress, but I am satisfied.”

Additionally, he said the agriculture ministry is embarking on a program to give money to farmers and community-based groups to provide meals to schools in specific areas. Clarke said $150,000 will be provided to support to these farmers and community-based groups. He also noted that the school feeding program, which provides juices made from local fruits, will be expanded to 136,000 students from the current 34,000.

Seeds of Change

Despite the changes taking place, Flanker’s reputation of a violent urban wasteland persists, alongside some all too real issues like poverty and malnutrition.

“No one outside of our community really wants to send their child here because of the area and the perception,” said Andre Hill, a teacher and bursar at Flanker Primary and Junior High School. “I know our history. In the past we would have gunmen running through the school shooting, but that has changed.”

“Today we have our police who patrol the community every day and our soldiers also have temporary housing here,” said Hill.

Flanker School currently enrolls 560 students between the ages of 5 and 18, almost entirely from the community. The school, one of 54 in the country identified as being in a high crime and violent community, receives support from USAID as part of the Obama administration’s Caribbean Basin Security Initiative.

“Our students are definitely at-risk youth with behavioral issues. Some are also slow learners, but we cannot blame them,” Hill said. “They come to school hungry, because their parents do not have the money to give them breakfast. That hunger then leads them to little or no attention in class, and then the desire to learn is gone, which leads them to be influenced by negative activities.”

Realizing that nutrition plays a critical role in a student’s performance, the school’s faculty, in 2012, introduced an agricultural program on the school’s grounds to grow cash crops—tomatoes, cabbage and bananas—and raise chickens. The school’s faculty, students and members of the community all volunteered their time to plant the crops. As part of their home economics class, students monitored and harvested the crops they planted. The crops and chickens were then sold throughout the community. On average, the agricultural program raised about $500.

This initiative allowed the school to raise enough food and funds to provide a breakfast feeding program for students who came to school hungry. But after five months, the project quickly came to a halt when many of the chickens died due to limited coop space. Because of lost funds, the school could not sustain the program.

“We would purchase 100 chickens and as much as 50 of them would die, which was sad because these chickens would give us the eggs for our students’ breakfast feeding program,” said guidance counselor Yvonne Medley-Reid.

That’s when the CAT stepped in, with help from USAID. To enhance the school’s agricultural project, in 2012, the CAT invested $15,000 and purchased construction and fencing material to expand the chicken coop. In addition, top soil was provided, through the Jamaica Constabulary Force, to enrich the farm’s rocky terrain, allow for additional crops, and strengthen relations between the community and police.

With the newly improved farm, the school is once again able to provide breakfast for the students. Meals include eggs, callaloo, pumpkin, bananas, sweet potatoes and corn. Sales of the crops and chickens have resumed.

“We sell a lot of our vegetables to the Rastafarian groups within the community, and other members love our home grown chickens,” said Hill.

“I am not one to have masonry skills, but it was wonderful to volunteer my time with the construction of the coop and farm,” said Meyers, the CAT team leader. “I care so much about what this agricultural project represents—unity among the JCF [Jamaica Constabulary Force] and the Flanker community and that the children are now able to eat. The Flanker agricultural project is a perfect example of the police and members of the community working together.”

Obrian Smith, 11, and James Benjamin, 12, take part in the school feeding program. “I love that I can eat ‘til my belly is full,” said Obrian.

“My favorite is the eggs and callaloo that I get for breakfast,” added James.

Both said that they love to pick the vegetables.

“We are now able to feed approximately 100 students from our breakfast program daily,” Hill said. “We have just over an acre of farm land, and with this new expansion, we should be able to feed up to 300 students—but it’s a process. There are still a number of students who are not on the program and they desperately need to be, so our aim right now is to try and assist those in need.”

He also said the program has helped cut down on students’ aggression: “The delight in a student’s face when he sees the products from his farming is indescribable.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.