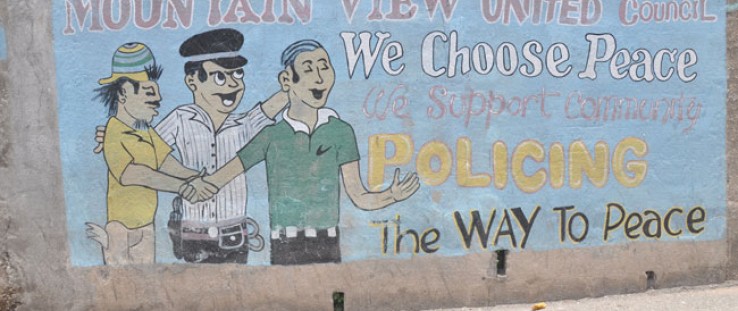

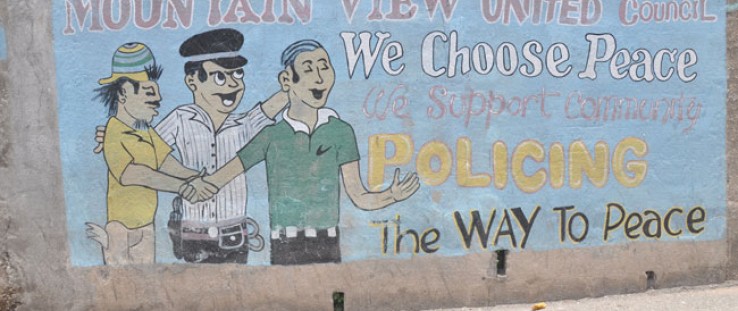

A mural painted by the citizens of the Mountain View community shows their partnership and support for the Jamaica Constabulary Force.

USAID

A mural painted by the citizens of the Mountain View community shows their partnership and support for the Jamaica Constabulary Force.

USAID

A mural painted by the citizens of the Mountain View community shows their partnership and support for the Jamaica Constabulary Force.

USAID

A mural painted by the citizens of the Mountain View community shows their partnership and support for the Jamaica Constabulary Force.

USAID

After closing her shop and fleeing her community of Gravel Heights, Paulette Simpson was happy to return home and reopen her grocery shop, confident in the ability of the Jamaica Constabulary Force to keep her safe from gangs.

A mobile police station in the community of Tredegar Park, Spanish Town, now gives residents the confidence to walk freely, conduct business and live peacefully in an area once plagued by gangs.

A mural that once paid homage to a Gravel Heights gang member has been destroyed. Paulette Simpson vividly remembers the days of terror. With a grimace, she recalls one of her darkest moments—when she was bombarded with the piercing sounds of gun shots, the shrieking of women and children, and the smell of blood filling the air in her small community of Gravel Heights, in Spanish Town, Jamaica.

“I was afraid,” she said. “Every day I lived in fear that my life would be taken away from me. I did not want to go out and work. I did not want to die.” In 2010, that fear drove Simpson to pack her bags, close her small grocery shop and seek refuge in a safer community.

Two years later, the terrible violence has now relented. In July, total major crime decreased by 49 percent over the previous year in the St. Catherine North Police Division where Spanish Town is located. Anthony Castelle, the division’s senior police superintendent, attributes community-based policing for the reduction. Homicide rates have been reduced, gang activities have been disrupted, and law enforcement officers are regaining the trust and confidence of the people they are sworn to protect, rekindling a partnership that had been badly tarnished.

The newfound security can be partially attributed to the Jamaica Constabulary Force’s (JCF) fight against crime and violence, with support from the USAID-funded Community Empowerment and Transformation (COMET) project. COMET focuses efforts on bringing together members of the community and the police in a new community-based policing partnership.

An Island Battleground

Gravel Heights is just one of many communities in Jamaica where criminal gangs caused many to fear for their lives. Gang members would often compete violently for resources and turf in the weapons and drugs trade. They extorted local businesses, and ran neighborhoods as their own fiefdoms. The crime and violence became overwhelming from the mid-90s through 2010, and citizens lost faith in the police. During the most intense periods of violence, five murders a week were reported in Spanish Town. Like Simpson, many left their homes to save their lives.

In 2006, at the height of the violence, USAID began working with residents, the JCF, the Government of Jamaica and civil society groups to come up with solutions. USAID’s COMET project launched community-based policing (CBP) programs, which required intense interaction between community members and the police. Neighborhood watches were set up; youth clubs came together to stand up against the violence; advertisements went up on buses and bumper stickers encouraging people to work with the police; and community consultative boards met regularly to discuss issues and activities with the police.

One of the greatest challenges was the distrust that had built up between the police and community members after many years of violence. People didn’t feel like they could trust the police to protect them and the police did not feel that they could depend on members of the community to give them the information they needed on criminals in the area.

“Prior to the program, there was a time when we, the police, could not walk within a number of high-risk communities without being shot. We would have to venture in armored vehicles to protect ourselves, and today it is much different,” said Stephanie Lindsay, deputy superintendent of the JCF. “The key element is engaging community members, finding out what their issues are and how we can go about resolving them as they are the ones who know best.

"We started this by taking the time to regularly walk into the communities and speak with the citizens on the streets or within their homes in an informal manner as our friends, as our neighbors. This simple gesture spoke volumes and started the process of building our relationship. Yes, some members were reluctant at first to speak with us. However, we have a new generation of youngsters that decided enough is enough with the crime and violence.”

The informal meetings later expanded into the formation of a number of police clubs across the country where citizens and members of the task force would meet on a weekly or monthly basis to discuss the communities’ challenges and to host talks with youth on how to empower themselves and make a difference within society without turning to the gangs.

High-visibility anti-corruption campaigns became a key element in building community trust. As a result of the program, the JCF has removed more than 400 corrupt police members. In addition, members of the force were extensively trained on community-based policing and how to better engage with community members. The training went further than reinforcing good police tactics, to instructing on fundamental ways to change the relationships between the police and citizens.

Confidence Boost

Recent monitoring data conducted by COMET indicates great improvement in levels of confidence in the police. Residents from communities within the St. Catherine North Police Division, including Gravel Heights, are saying that they are more likely to report matters to the police now than they were two years ago. More than 83 percent of citizens within the North Division stated that their community leaders work closely with the JCF to build safety and security programs for the community, with 75 percent of citizens reporting that they participate directly in such programs. Eighty-seven percent of respondents expressed confidence in the police’s ability to control crime and violence in the division. In addition, the JCF’s anticorruption branch reports that more people are dialing a crime reporting hotline that USAID helped establish.

Further support came in 2009, when President Barack Obama introduced the crime and corruption-fighting Caribbean Basin Security Initiative, which added resources to efforts like community-based policing that make progress against trafficking of drugs and weapons. “Three years ago, we were in 57 communities doing CBP, and today we are now in 700 communities,” said Lindsay.

After six and a half years of transforming the law enforcement landscape in a very violent corner of the world, the successful COMET project came to a close in September 2012. Approximately 9,000 officers across the island have been trained in community-based policing, and new USAID efforts will ensure that these efforts are sustained to meet future needs.

Paulette Simpson has returned to her community and resumed her shop-keeping duties, her grimace replaced with a smile. “It is safe,” she says, “I feel safe.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.