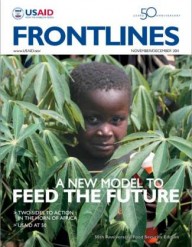

Cashew farmers and their children sell roadside as part of Mozambique’s informal cashew trade. Around three-fourths of the country engages in agriculture, mostly subsistence farming.

Kelly Ramundo, USAID

Cashew farmers and their children sell roadside as part of Mozambique’s informal cashew trade. Around three-fourths of the country engages in agriculture, mostly subsistence farming.

Kelly Ramundo, USAID

Cashew farmers and their children sell roadside as part of Mozambique’s informal cashew trade. Around three-fourths of the country engages in agriculture, mostly subsistence farming.

Kelly Ramundo, USAID

Cashew farmers and their children sell roadside as part of Mozambique’s informal cashew trade. Around three-fourths of the country engages in agriculture, mostly subsistence farming.

Kelly Ramundo, USAID

Cashew may be informally known as a poor man’s crop, but that reputation may have more do to with the sandy, nutrient-poor conditions in which the crop thrives than its impact on farmers’ incomes in parts of East and Southern Africa, Southeast Asia and South America. When cultivated skillfully, the bean-shaped under-hanging of the juicy, bitter fruit can be a life-changing commodity.

In Mozambique, a once dominant cashew sector has slowly been regaining steam in recent years after decades of conflict and unfavorable economic policies left it crippled in the late 1990s, according to John McMahon senior agriculture policy adviser for USAID/Mozambique. During the last five years, the Mozambican cashew processing industry, with USAID assistance, generated approximately 4,500 new jobs in rural Mozambique, and contributed directly to the income of 22,500 family members. Thirty-nine percent of those new jobs are held by women.

In most districts where factories are located, they are the only source of wage income. Since 2002, a rash of small, labor-intensive factories have combined with the countries’ more informal road-side sellers to produce over 60,000 tons of the nut, about half of which were exported for around $40 million.

What is clear is that over the past decade, the beloved nut has reemerged as one potential path out of poverty for rural Mozambicans up and down the production chain: from the farmers who grow it to the factory workers who process it. Buoyed by ballooning demand, and with USAID assistance, the cashew is helping to transform the economic structure of rural areas in one of the world’s poorest countries.

If Mozambique’s cashew industry can be imagined as a pyramid, at its base are the country’s roughly 3.7 million small-scale, subsistence farmers, 1 million of whom engage in cashew production—managing an estimated 18 million trees in the country’s northeast.

USAID and its partners are helping reintroduce the lucrative tree to smallholder farmers, teaching growing, grafting and pruning techniques for maximum yield, and encouraging them to unite into associations to pool crops and fetch higher prices for their raw material.

And with world prices rising and expected to remain steady, life is changing for many growers in Mozambique’s cashew production areas located in Nampula, Zambezia, and Cabo Delgado provinces.

Arlindo Chaleira received plants and the technical know-how to see them thrive through USAID implementer ADRA (Adventist Development and Relief Agency). With just one hectare of land, he is the epitome of the smallholder farmer benefiting from the nuts’ global popularity, and from a network of USAID-supported technical advisers.

“I used to plant things any which way,” he says. “This project teaches me how to plant. Life has changed. With this knowledge and one hectare, I can get 500 kilos [of nuts].”

Chaleira now combines his crop with other growers in his farmers’ association, and with the profits, he has made enough to place all eight of his children in school, an anomaly in rural Mozambique.

But the farmers are only one part a long chain linking crop, industry, and markets in the Southern African country. The value of cashew increases considerably where there is a functioning processing industry to export the kernels to higher-end buyers in the West.

Foot Pumps and Fair Trade

At the opposite end of the chain, at CondorNuts in Anchilo, Nampula province, hundreds of Mozambicans operate foot pumps to shell raw cashews, their hands stained an oily black from the acidic shell liquid. Instead of being shipped abroad in their raw form, as most of Mozambique’s cashews are, or roasted on open fires and sold cheaply on the side of the road in the informal market, these high-quality cashews are being processed for export mainly to Europe and the United States with USAID assistance.

Because of how easy it is to break a cashew, and the premium paid for perfect nuts, humans are better than machines at shelling the cashews. At its two factories, Condor employs around 2,000 workers to both extricate the fragile nut and then export it to Europe for further processing (flavoring, roasting, and retail packaging).

Silvino Martins is a young Mozambican businessman and the manager at Condor, one of the 12 cashew-processing factories in Nampula province.

Though he is situated at the top end of the value chain, he knows—thanks in part to USAID-supported technical advisers—that his success is inextricably linked to that of the farmers that provide his raw material and the workers processing it.

Because of these linkages, Martins is looking at ways to help his suppliers increase their yields.

“What you are getting now is some of the processors working to encourage more planting of quality seedlings. Though it might be five years until those come into production, you are seeing some interest by industry to say: ‘How can we influence here?’” explains USAID’s McMahon.

In his factory, Martins pays his employees a guaranteed minimum salary and treats them well: offering child care and up to two meals during their shifts. If the value chain continues to improve, Martins is convinced that Mozambique can reemerge to rival Brazil, India and Vietnam as a premier exporter of processed nuts.

Jeanne Downing, a USAID value-chain expert, explains that a functioning value chain is not about competition among industrial buyers and local sellers, but rather, symbiosis: “In the case of cashews, you’re not really competing with your neighbor; you are really competing with Vietnam. You’re really competing with Brazil. And unless, as an industry, you can find a way of working together, none of you will win,” she says.

Up and Down the Chain

In Mozambique, as in many of the countries where USAID works, the Agency and its partners are active up and down the value chain: imparting technical knowhow to farmers; helping processors access finance, and then working with them to ensure healthy competition and standards for workers; fostering public-private partnerships; helping with quality control for the end product and marketing it to international buyers; and even working to influence the policy environment for the industry as a whole.

In the case of Mozambique’s Condor, the Agency has helped partially guarantee a bank loan to get the factory up and running and see that it expands.

McMahon compares the full range of USAID assistance to a three-legged stool: “The first leg is strong focus on technologies [such as research, improved crop varieties, production processes, and fertilizer] to improve productivity for both income and nutrition; the second is integrated programs, so that means building capacity of community-development and farmers groups and giving them better access to inputs, markets, and credit; the third is agribusiness—linking farmer associations together into unions, then federations, so they have better access to international or regional markets and can benefit from economies of scale.”

According to McMahon, it is those three pieces working together that makes the program so successful. From 2005 to 2008, the nine processing factories supported by USAID operating in Nampula and Zambezia provinces generated $31 million in revenues by exporting processed cashews to the European markets. These nine plants, which generated employment for about 3,400 Mozambicans, had a production capacity of about 20,000 tons of cashews, compared to just 120 tons in 2001, when the first of nine units supported by USAID began operating.

Cashew is not the only value chain that USAID supports. In Mozambique, there is also a focus on oilseeds (groundnuts, sesame, soybeans), fruits (bananas, mangos, pineapple), and pulses (cowpeas, pigeon peas).

And throughout its global network, the Agency has incorporated integrated support of value chains into the U.S. Government's flagship food security program, Feed the Future.

According to William Garvelink, who helped stand up the new bureau leading the initiative and is now at the Center for Strategic and International Studies: “[Feed the Future] looks at the entire value chain, so the U.S. Government can intervene in any way from planting seeds to marketing products; whatever’s needed, we can quickly be involved. It’s a broad spectrum.”

Downing explains that the Agency’s value-chain strategy is anchored in the reality that a focus on production must also consider markets. “There are no incentives for farmers to produce crops unless they can sell them,” she says.

To Plant a Tree

In Mozambique, as in many places with emerging industries, the cashew industry still faces many challenges, among them, how to massively increase production.

Because cashews trees have a productive lifespan of around 50 years, it often takes a great deal of effort to convince a farmer to replace a fully-grown tree—albeit an unproductive one—with a sapling that will take five years to yield nuts. One of the approaches that may work, according to McMahon, is to actually involve processors in commercial seedling production, which they can then sell to farmers for a small price, “giving them a commercial interest in that tree.”

Another opportunity, says McMahon, is to start supporting larger-scale commercial agriculture “that includes opportunities for the small-scale farmers either as out-growers, contract farmers, or, in some cases, laborers.”

But still, worldwide demand for cashew is increasing at around 5 percent annually. To help quench that thirst, Mozambique now has around 10 processors, when years ago there were virtually none, and the industry is netting to smallholder farmers $20 million worth of kernels purchased per year. Unless the West decides to shake its nut craze, there is no where to go but up. Martins of CondorNuts is optimistic: “By improving all parts of the chain, ultimately...cashews produced here will be just as competitive as in India.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.