Meo tribe children and Hal Freeman, right, look at textbooks provided by USAID in Laos. In the background, a parachute serves as a roof.

Meo tribe children and Hal Freeman, right, look at textbooks provided by USAID in Laos. In the background, a parachute serves as a roof.

Meo tribe children and Hal Freeman, right, look at textbooks provided by USAID in Laos. In the background, a parachute serves as a roof.

Meo tribe children and Hal Freeman, right, look at textbooks provided by USAID in Laos. In the background, a parachute serves as a roof.

Hal Freeman was already immersed in the field of education—first as a high school teacher, and on track to becoming a principal. After obtaining a master’s degree in education administration and supervision, he found out through a contact at the State Department that USAID had started a new program for junior officers.

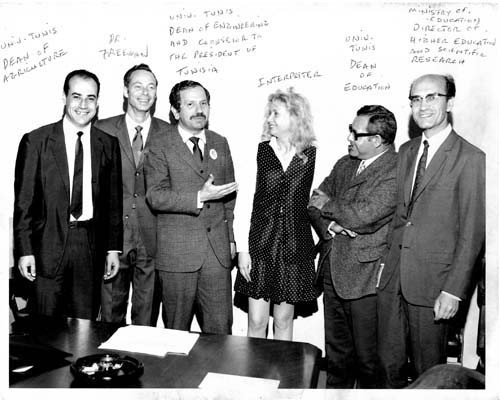

“The year was 1957,” he reminisces. “Education officers in missions at that time were career professional educators, all of whom were not the management, but rather the technical type.” There were about six or seven technical specialists working in missions—with impressive backgrounds. They had been professors, deans of schools, superintendents, and chief state school officers. The Agency was looking for bright young people with three to five years of teaching experience and a master’s degree to work alongside such experienced technical specialists. The theory was that younger officers were more adaptable to cultural factors, travel, and hardship. They could develop camaraderie with local people.

1957 - 1959

Freeman’s first assignment was in Thailand, where he was the only young officer in the education team. The experienced FSOs took him under their wing. He pauses and reflects, “I learned more from working with these people than what I would have learned from 30 years teaching experience.”

One of the main projects Freeman worked on in Thailand was a project on education development in a handful of provinces—four elementary schools, two secondary schools, and one teacher training school. This project stands out in his mind because they “worked side by side with all levels of the Thai Ministry of Education.”

He adds: “What made our work successful was our willingness to put ourselves in the Thai Ministry of Education’s shoes. The ministry had its own internal dynamics and we [USAID] had to merge what we thought needed to be done with their way of doing things and what they wanted to accomplish. This way we were able to find the middle ground.”

As an aside, Freeman posits that those projects where technical experts moved ahead more or less on their own to “get something done” were often not sustainable— after the technical experts left, much of his work would be dropped.

“Why?” he asks rhetorically. “Because, however qualified the officer, the people of the country did not think of his work as theirs. It took a lot longer for people to say it was their project, theirs…and it paid off in the long run….”

Freeman finishes relaying his experience in Thailand with an observation: “The Thais are unique because they learned how to take the ideas of outsiders and adapt those ideas to their political and cultural situation. They wouldn’t just follow in the precise way USAID wanted.”

In my mind, this characteristic does not seem to be uniquely Thai. It did, however, sound like a goal we should all strive for at USAID—to enable developing countries and their people to own and craft their own solutions. It should be our job, as development professionals, to steer them in the right direction, which is the path of their choosing.

1976 - 1978

“What was your favorite place to work, and why?” I pose to him.

“Pakistan, without a doubt,” he answers. [Freeman headed the Near East/South Asia Education Program in Washington from 1970-1976 before heading to Pakistan.] “The guys in the Ministry of Education planning unit were dedicated, bright people who cared about their country’s development and worked around the clock. I had the greatest joy working with them. [Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali] Bhutto had just been assassinated and General Zia [Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq] had just taken over. In the ‘70s, Pakistan had a large population, yet only about 20 percent of boys and 7 percent of girls were in schools.”

Freeman spent two years developing a rural primary education program with a focus on female education. “We almost had the signature on the dotted line when the issue of nuclear proliferation came up—to put it lightly—and we had to close the program before it even began. Any ongoing projects could continue but no new programs could get started,” he says. Freeman persevered and worked with World Bank mission staff to adopt the program and carry it through for several years.

Initiating such a program in a conservative society was challenging. The education team theorized that supply could create demand and that, if they supplied the teachers and the classroom, 40 to 50 percent of the women would go despite society’s perceived restrictions. Female teachers came from urban areas and were provided dormitories, so they could teach in rural areas. On the weekend, the teachers would go back to their cities.

As a complement to the traditional classroom in schools, the team also designed the project to enable some “schools” to be conducted in women’s homes. Many rural mothers were more likely to bring their daughters to another women’s home than to a formal school, just like 18th century English dames schools.

“In light of all the types of development USAID does, why is education important?” I ask.

“The effect over time of having a literate workforce is undeniable,” he responds. “Education yields trained men and women who contribute to society in the workplace and in families through, for example, health and family planning—waiting longer to have children and spacing them out so as to make time for a career. There is a broader effect than learning ‘the three Rs.’” Education wasn’t the focus in some missions. Mission directors cared about infrastructure—roads and dams—and short-term gains. A critical aspect of Freeman’s job was to advocate for education, despite its long-time horizon. There was also a difficulty in not swaying to the fads in education, but rather, to determine critically what the country needed the most, and what could be achieved, given the ministry and host country leadership interests. That could mean basic education, workforce development focused on technical skills or higher education. “What was the best thing about being an education officer?” I ask.

Freeman responds: “It was an exciting career, working with top leaders of education in a country, the intellectual atmosphere, USAID’s dedicated staff, and those on the forefront of knowledge.”

Freeman provides this advice to new Foreign Service Officers: “Because an officer is helping a country develop, it is important to be eyes wide-open, not dewy-eyed. Listen and learn from your host country counterparts.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.