Emily Mutai, SUWASA

Emily Mutai, SUWASA

Emily Mutai, SUWASA

Emily Mutai, SUWASA

Imagine a business that cannot track its inventory. It doesn’t know how much it has or how much its sells. As much as three-quarters of its shelved products may disappear, randomly stolen or ruined by misuse. Some buyers do not pay, some sales go unrecorded, and customer lists are out of date or inaccurate. The owner may have a vague sense of how the stock disappears but is at a loss as to what to do. Even if the product meets minimum standards, how long can the business survive without regular infusions of funds?

A water utility can be in very much the same position. Its product is treated water, which it delivers to customers, usually through a network of pipes. The difference between the water that the utility produces and the water that it is paid for is called “non-revenue” water. Like the business with serious inventory and sales problems, many water utilities are crippled by water losses that they cannot account for or reverse.

Some level of loss is normal and expected. A utility that keeps its losses at 25 percent or less is doing well. In sub-Saharan Africa, however, most utilities are losing far more than that.

In Togo, Cameroon, Republic of Congo and Swaziland, the national water companies estimate that around one-third of their water is non-revenue. The utility in Kisumu, a major city in Kenya, loses half of its water, as does the national water company of Ghana. And the state water board of Bauchi in northern Nigeria guesses that its losses may reach 75 percent, but it is not certain since it is not sure how much water is in its system or how much it sells (see sidebar below).

The solutions to these problems do not always require massive investments. Sometimes the solutions, like those being drafted and implemented by USAID, are about new approaches, new partnerships and new tools.

Utilities on the Precipice

What causes these high levels of loss? Most people think first of broken pipes. We have all seen flooded streets or water pouring out of hydrants. They can amount to large losses, but they are also easy to spot and stop. More insidious are the losses from institutional corruption or user theft, broken meters and billing inaccuracies. They require more fundamental changes in thinking or adjustments in systems, but improvements can have a far-reaching impact on a utility’s operations.

Most utilities in Africa live on the edge of a financial precipice. They cannot cover their regular operating costs. They do not provide full services to their customers, and they cannot repair or expand their networks, making delivery less fair. Nor can they keep up with rapid urban growth that demands they extend the network to a city’s edges. Also, without financial resources, utilities cannot ensure the quality of their supply.

Utilities in sub-Saharan Africa lose almost $600 million in revenues yearly, or 3.4 million cubic meters per day, from water losses, a significant portion of what the United Nations estimates is needed to achieve the Millennium Development Goals in improved access to water and sanitation.

In 2012, USAID joined with the African Water Association (AfWA) in an ambitious program to halt the constant creep of higher and higher water loss levels. Through its Further Advancing the Blue Revolution Initiative (FABRI), USAID and AfWA are working with 23 national and city water companies and state water boards in 20 countries in east, central, west and southern Africa.

Strengthening African Expertise

The USAID/AfWA program is the first continent-wide attempt to tackle this devastating problem in a serious, sustained way. It focuses on determining the real extent and causes of losses at the utility level, designing and carrying out action programs to reverse the losses, and strengthening African expertise to solve these problems now and in the future. The program is reinvigorating AfWA while raising its profile and credibility as the regional technical leader in water and sanitation.

The program began with the creation of the permanent Non-Revenue Water Task Force under AfWA’s umbrella. It draws its 15 members from water utilities in 13 French- and English-speaking countries. They tend to be directors of non-revenue or operations departments, but some are also directors of their utilities.

Members of the task force design, guide and monitor the AfWA/USAID program. Their training in the latest thinking about non-revenue water by some of the world’s leading experts took place in two regional workshops in 2012—Nairobi in June and Ouagadougou in November.

Task force members are applying their skills in their own utilities as well as others throughout Africa. As a first step, they are conducting water audits in all 23 utilities. A team of three task force members from different countries work together for a week to analyze the institutional and network conditions and develop a detailed water balance for the utility.

This is often the first time that the utility has a comprehensive understanding of how much water it has and how much it uses. A task force member from Ghana has conducted audits in Kenya and Uganda. His counterparts from those countries have carried out audits in their own utilities and in Swaziland. Others from Cote d’Ivoire and Togo have worked in Cameroon. Several donors have praised the program for giving task force members the opportunity to collaborate on common water loss problems by visiting each other’s utilities and preparing joint audit assessments.

Following the audit, the water utility develops a plan to reduce non-revenue water on its own or with the help of a task force member. The plan clearly lays out what can be done to reduce water losses in the short- and long-term through the actions of the utility, in partnership with FABRI and AfWA, or with the assistance of other international donors. While FABRI and AfWA lack the funding and mandate to make major network repairs or replacements, they will work with utilities to develop proposals for major outside investment.

AfWA will use this model beyond the initial group of 23 utilities in the coming years in the hundreds of water utilities in Africa that experience high levels of water loss. While major renovation schemes are a costly fix outside the reach of most utilities, there are many actions that will lead to dramatic improvements, including introducing production or consumer metering, better district operations and monitoring, more accurate billing systems, more effective consumer-oriented practices, better response times to reports of breaks, and creation of non-revenue departments with better trained staff. FABRI and AfWA will work with the utilities to introduce these management practices and tools.

Strong local technical skills coupled with targeted actions can make more water available to customers and put utilities on a much-improved financial footing. We anticipate three important outcomes of the program. First, we expect a measurable reduction in non-revenue water in African utilities. Second, we expect that the Africa Water Association will grow in recognition as a technical leader in the sector for hundreds of water utilities across the continent. And third, we expect that, before developing costly new water resources, governments will consider using non-revenue water practices and tools to increase supplies and improve the lives of their people.

Urban Nigeria Taps In To Town Water

Although water is plentiful in Nigeria’s Bauchi state, situated 326 miles northwest of the country’s capital city of Abuja, only 36 percent of the population receives a clean, reliable supply. While there are 600,000 people living in the state capital of Bauchi town, only 17,000 households are legally connected to the municipal water system. In May 2011, USAID agreed to help the town restructure its water board and enact other reforms to help increase access.

Bauchi town residents get water from a public standpipe. Residents without access to water at their houses must walk long distances to line up for water at public standpipes. In December 2011, USAID’s Sustainable Water and Sanitation in Africa project signed an agreement with town officials to help them restructure the Bauchi State Water Board, which is responsible for the locale’s water and sanitation sector.

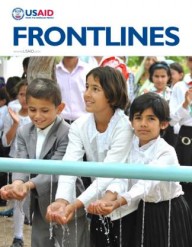

The partnership between USAID and the water board produced a name change for the utility, now the Bauchi State Water and Sewerage Corporation. The autonomy and stronger management systems under the new reforms are a critical step toward improved performance and increased access to water and sanitation services. These children are but three of the town’s residents who require water for everyday needs like washing hands and cooking meals. Demand for water in urban areas like Bauchi exceeds 200,000 cubic meters per day—nearly four times the volume the utility is currently able to pump to its customers.

Surveyors interview a household about water usage. Part of reforming the utility involves a customer enumeration exercise that has helped capture over 30,000 illegal connections. Accurate customer records from this exercise will lead to efficient billing and collection, and eventually improve revenue for the utility. Pictured: Two enumerators question a young man and his mother about their household size, source of water supply, and willingness to pay for improved water services.

Surveyors review a map showing households selected to take part in the survey. Once they complete their task, customer records should be up to date, with water bills arriving soon after. USAID’s partnership with the Bauchi State Water and Sewerage Corporation is bringing real hope for improved water and sanitation services for the residents of Bauchi. Following the state’s commitment to reforms and an investment of $4.8 million of state government funds, Bauchi state was selected by the World Bank as one of three Nigerian states to benefit from the $400 million third National Urban Water Sector Reform Project. This financing is critical to upgrading and extending the water infrastructure for Bauchi residents throughout the state and improving management by the water utility. This represents a significant leverage of USAID’s $4 million investment in the Sustainable Water and Sanitation in Africa activity in Bauchi.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.