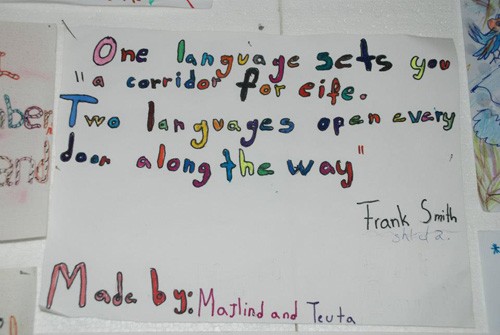

A EUCOM/USAID program in Macedonia provides diversity training, technical assistance, and incentives to school boards, principals, teachers and administration officials to support ethnic integration.

USAID

A EUCOM/USAID program in Macedonia provides diversity training, technical assistance, and incentives to school boards, principals, teachers and administration officials to support ethnic integration.

USAID

A EUCOM/USAID program in Macedonia provides diversity training, technical assistance, and incentives to school boards, principals, teachers and administration officials to support ethnic integration.

USAID

A EUCOM/USAID program in Macedonia provides diversity training, technical assistance, and incentives to school boards, principals, teachers and administration officials to support ethnic integration.

USAID

During the unveiling ceremony to dedicate renovations at a school in Tetovo, Macedonia, Michael Ryan watched teens in traditional dress perform folk dances.

Ryan, a retired U.S. Air Force colonel who serves as a senior civil servant with U.S. European Command (USEUCOM), represented the U.S. military during the event, the culmination of a joint project between USAID and USEUCOM to increase stability in Macedonia through interethnic integration in schools.

“Their dances tell a story in the pride of their culture and their desire to make sure their culture continues to survive,” Ryan said. “They are so warm and welcoming and so dedicated to improving themselves, in this case though education, that you immediately become captured by their charm and their enthusiasm.”

That wasn’t always the case. A decade ago, Macedonian armed forces and Albanian insurgents fought each other in a conflict borne largely from ethnic differences.

Today, the sides are no longer fighting, and the military and USAID are collaborating on targeted projects that promote peace between the former rival groups through school integration.

“In the case of Macedonia, it’s a very small investment, about $300,000 per year [from USEUCOM],” said Brig. Gen. Blaine D. Holt, director of logistics at USEUCOM.

“For that, we are supporting an interethnic education program that one day will be the stability of the future and help prevent conflict.”

Each U.S. military combatant command, or “COCOM,” is a geographically oriented, strategic-level organization led by a four-star commander, and has a directorate for humanitarian assistance and civic engagement. Each COCOM also has a USAID senior development adviser on staff. Humanitarian assistance and civic engagement is a large part of EUCOM’s strategic efforts and is coordinated with USAID.

USAID often has more experience in a country, with a focus on the local areas and established partners to implement programs. Military officials say that partnering with USAID allows USEUCOM access to communities and to offer assistance where it can benefit people on a personal level.

Strategically, USEUCOM and USAID may engage in certain projects for different reasons, said Ame Stormer, who runs the program at USEUCOM.

“But there’s often an overlap in achieving both institutions’ goals by working together,” Stormer said. “It makes sense.”

Cohesion Is Key

Interethnic cohesion is key to stability in Macedonia—part of USEUCOM’s strategic goals for the region. That’s why USEUCOM provides $300,000 annually to fund 10 school renovations per year in the country, which is coupled with USAID’s $1 million annual investment to support interethnic integration in education.

USAID works with local educators to develop interethnic tolerance in schools. To qualify for a renovation project, schools must show proven progress toward that goal to a USAID committee that includes a USEUCOM officer at the U.S. Embassy.

“When those schools have progressed to USAID’s satisfaction, they are able to qualify for a renovation project,” said Lt. Col. Michael Evans, USEUCOM humanitarian assistance program manager. “The projects are small scale, about $30,000 each, but USAID works directly with local contractors, so we get a lot done with that amount. This is a great example of a long-term, sustainable, interagency activity that is in alignment with, and prioritized within, our country strategy and the theater campaign plan.”

Coordination, in some cases, serves to avoid duplicate efforts. But the relationship goes beyond that. In an era of constrained resources, U.S. Government agencies working toward common goals overseas should look for ways to collaborate, said Stormer.

USEUCOM’s area of responsibility covers 51 countries in Europe and Eurasia—some of which have no USAID presence or activities to match USEUCOM’s humanitarian assistance efforts.

“When the opportunity exists, we want to ensure that USEUCOM and USAID's programs in the region are mutually reinforcing,” Stormer said.

In Macedonia, the parallel efforts led to partnership on education. In Albania, USAID and USEUCOM support telemedicine projects, which provide health-care services via information technology. The organizations also work together in Ukraine.

At the ceremony in Tetovo, Ryan was first struck by how different things are in Macedonia, compared with where he lives in Germany. But as he spoke, with interpreters translating his comments, he glanced around. His eyes caught people smiling. He saw children playing and laughing. He saw folks talking on the street corner.

“What strikes you is that we have the same desires. They want a home, a nice place to live with their families,” Ryan said, reflecting on his stay in Macedonia.

“Everything that makes a wonderful life is there.”

Rick Scavetta is with U.S. European Command.

Working Together Is the Lesson

By Sharon Kellman Yett

“Your disagreements nurture the dragon’s might and evil. You must stop fighting!” said the prophet of the planet. She warned the people of the two villages that the dragon would destroy them all unless they would learn the language of the other, celebrate their differences, and live together. “That’s the only way to beat the dragon,” she informed them.

This is the lesson of Dragon Story, a fable created and filmed by students at Arseni Jovkov High School in Macedonia who participated in workshops on creative expression and interconnection as part of the USAID Interethnic Integration in Education Project, which is co-funded with the U.S. European Command (USEUCOM).

These workshops help students think critically about stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination. The students also learn how to work as part of ethnically mixed teams while honing their video-making skills and producing short YouTube videos for their classmates advocating for intercultural exchange.

“The workshops helped us to get to know each other but learn more about ourselves at the same time,” said Anita Antik, a student at Arseni Jovkov Secondary School. “It helped us recognize our own prejudices that we should definitely not have as young people. The change we want to see around us should start from us. The … real results of these workshops are definitely our experience and our friendship.”

Macedonia is a culturally rich nation that is home to many ethnic groups—Macedonians, Albanians, Turks, Roma and Serbs, Bosniaks and Vlachs, and others. Following the break-up of the former Yugoslavia, relations deteriorated to the point that a conflict erupted in 2001 between ethnic Albanians and ethnic Macedonians.

The Ohrid Framework Agreement, signed on August 13, 2001, ended the fighting, but some tension remains between ethnic groups in the country.

For example, the use of different languages of instruction for students from different ethnic groups has led to a parallel educational system. Students from separate ethnic groups, with their own languages and cultures, tend to interact only with students from their same group. This, in turn, encourages parallel lives, thereby promoting distrust, ethnic stereotypes and prejudices.

“It is very sad that our young people from different ethnic origins live close by and attend the same schools, but actually don’t know each other,” said Lela Jakovlevska, manager of USAID’s Interethnic Integration in Education Project. “Living parallel lives is not natural for youth who have the same desires, aspirations and plans for a good future. Only building bridges of trust and close contacts can remove these invisible barriers and enable normal human interaction where commonalities and differences are appreciated.”

Towards this aim, USAID’s four-year project is working to build broad public understanding of the benefits to all citizens that will arise from integrating Macedonia’s education system. Begun in December 2011, the program has four components: to raise awareness of the importance of ethnic integration in Macedonia; to equip school officials with the skills needed to integrate their education programs; to establish demonstration schools that serve as models for the entire country; and to provide funding to help renovate schools to provide a better learning environment.

The $5.2 million project is designed to help provide interethnic training and education to 350 primary and 100 secondary schools, and renovations to 40 schools through its tenure.

‘We Can Solve Any Issue’

Extracurricular activities such as the video program that bring students together are important, but they are only a small part of the project. One initiative has been the creation of school integration teams—made up of school administrators, support staff and teachers—who use different languages of instruction. These multilingual teams receive diversity training and learn how to increase understanding among culturally diverse groups. These programs provide a valuable model for other teachers and school administrators across the country.

“We were so encouraged and motivated to establish a partnership after talking to the director of the Naim Frashëri Primary School from Tetovo,” said Elizabeta Donchevska-Lushin, the director of Dame Gruev Primary School in Kuklis village. “We recognized and acknowledged that together we can solve any issue and the challenges we encounter. Thanks to USAID, we can realize activities with our partner school and overcome the prejudices and stereotypes we have.”

The project is also working with Macedonia’s Bureau for Development in Education, the national Vocational Education and Training Center, as well as the State Education Inspectorate so that ethnic integration indicators are incorporated to the School Performance Quality Indicators and these efforts will be sustainable.

USAID and USEUCOM have come together for the last part of the project—a renovation program for selected schools that have participated in the interethnic education program. All municipalities and schools that have successfully participated in the program and are willing to help share in the financial costs are eligible to apply for renovation funding—an added benefit for schools that have fallen into disrepair.

So far, USEUCOM has committed a total of $1.2 million to the school renovation program. To date, $900,000 has been or is being transferred to USAID, and the remainder will be transferred next year. Eleven schools across the country have been renovated so far, 10 more are currently being renovated, with a total of 40 planned by the program’s end.

In addition, parents and teachers sometimes take part in the renovations by dismantling old parts of the schools and transporting them to disposal sites. During these activities, parents can also spend time with neighbors from another ethnic group. At Marshal Tito Primary School in Bansko, the project renovated the school roof, installed a ramp to improve access for disabled people, and provided tools for better facility maintenance. Inspired, now the municipality plans to renovate the school’s facade.

The school renovations represent just one part of USAID’s and USEUCOM’s joint efforts.

“Through our USAID partnership, and the IIEP [Interethnic Integration in Education Project] project design, we achieve a cumulative effect far greater together than would be achieved separately,” said Lt. Col. Mark V. Watkins, chief of the Office of Defense Cooperation in Skopje. “Interethnic cohesion is key to stability in Macedonia—part of USEUCOM's strategic goals for the region—and we are making a positive difference together.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.