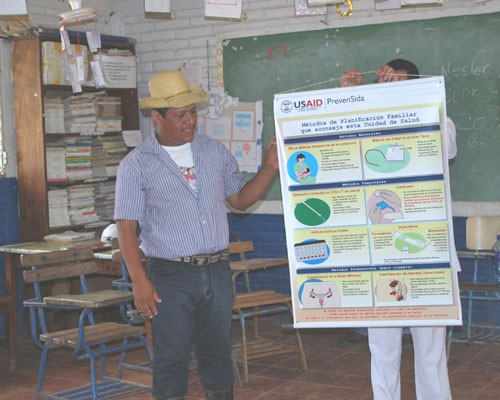

Maryuri Arellano gives a health talk on adolescent pregnancy prevention.

Kimberly Cole, USAID

Maryuri Arellano gives a health talk on adolescent pregnancy prevention.

Kimberly Cole, USAID

Maryuri Arellano gives a health talk on adolescent pregnancy prevention.

Kimberly Cole, USAID

Maryuri Arellano gives a health talk on adolescent pregnancy prevention.

Kimberly Cole, USAID

Trinidad Hernández lives in a wood-panel house with a zinc roof and a dirt floor in La Patriota, Nicaragua, a small rural village near the center of Nicaragua. The 39-year-old is a cattle farmer and volunteers as a health promoter. He enjoys the respect his community gives him as a person of authority who helps solve some of the health problems they face. He is part of a community-based family planning program that has been supported by USAID since 2003 and has been integrated into the Nicaraguan Government’s national health strategy.

Today, more than 1,000 men and women like Hernández are involved in the country’s ambitious community-based efforts to improve health by helping parents decide the size of their families. These community health promoters educate and supply contraceptives to their neighbors who live in the most remote villages. Buttressing the approach is a USAID-sponsored 2011 study [pdf, 1,062 kb] indicating that, when men are involved as partners and community members, there are lasting improvements in reproductive health.

The number of male family planning promoters in Nicaragua has grown dramatically since 2006. Hernández reports that “the women in my community have confidence in me because I offer all of the [family planning] methods that are available and I give them enough information so that they can choose the method that is right for them. And then I make sure to always have their next supply ready.”

Programs like this, which are part of the USAID graduation strategy in countries like Nicaragua, gradually prepare them for the Agency’s departure. The goal is to maintain the successes achieved with assistance both during and after graduation. Nicaragua is an especially successful case in a region where improved education for women, greater economic opportunity and increased availability of family planning have reaped enormous benefits overall, say USAID/Nicaragua officials.

In Nicaragua, specifically, increased use of family planning has coincided with a reduction in maternal mortality by almost a third since 1980.

From Six to Two

In the 1960s, the average woman in Latin America had six children and many died in childbirth. Back then, most women in remote areas didn’t have access to family planning or know that they could space or limit their pregnancies.

Today, most women have between two and three healthy children.

Infant mortality has fallen faster in Latin America and the Caribbean than anywhere else in the world, declining by 70 percent since the 1960s. Child mortality has declined by 57 percent and the region’s maternal mortality ratio has dropped by 41 percent since 1990.

According to Marianela Corriols, USAID/Nicaragua’s project development specialist for health, this is not a coincidence. “There is strong evidence that the dramatic expansion of family planning services during this period was a major factor in saving these lives, by giving couples the ability to space their children’s births, and limit their family size, according to their own desires,” says Corriols.

While USAID has been the world leader in family planning funding since the 1960s, Corriols notes that the Agency was mostly an outside facilitator of country plans. “It is the leadership of host country governments and civil society that have led to these stunning results,” she says.

Regional Phase-Out

Because many Latin American and Caribbean countries have increased the number of women and couples with access to family planning, and because maternal and child health has improved, U.S. Government assistance for family planning is being phased out.

In 2004, USAID created a set of criteria to identify countries that were approaching self-sustainability of their family planning programs and worked with host countries on phase-out strategies. These strategies included contraceptive procurement and storage; reforms to protect family planning budgets; access to services for the most underserved populations; and quality family planning services, which includes method choice and affordability.

In one of the most dramatic examples, the Government of Nicaragua, through successive administrations, increased its own funding for family planning commodities from $9,000 in 2006 to over $2 million today.

Other countries in the region, including the Dominican Republic, Peru, El Salvador, Paraguay and Honduras, have also experienced gradual, strategic reductions in USAID family planning funding. These countries have been preparing for two to eight years for USAID’s departure in family planning support, and the successes achieved have been sustained. All but Honduras, which is scheduled to complete the reduction in support this year, are now completely graduated from the Agency’s family planning support.

A Serious Public Health Problem

Trinidad Hernández, who sees about 60 clients per month, volunteers for the USAID-backed project Famisalud that developed Nicaragua's community-based family planning strategy with the Ministry of Health. It focuses on the most remote and hard-to-reach populations.

Hernández has set up a separate room within his house so he can privately counsel community members while also going door to door to meet with women who depend on his supplies every month. He gives talks in the village’s dilapidated but functional school because he understands how important it is to reach young people with information and resources.

He reports that when he goes to the local clinic to pick up supplies for his neighbors, the pharmacy is always fully stocked. His experience mirrors national data that shows a stockout rate of less than 1 percent, decreasing from 37 percent in 2006—a stunning logistics achievement that few developing countries have matched.

Even with such successes, some tough challenges remain.

Maryuri Arellano, 17, is also a family planning promoter, yet her journey was based on difficult personal experiences. At age 15, she became pregnant, like many of her adolescent peers. In some parts of Nicaragua, 40 percent of women giving birth in health centers are adolescents.

Adolescent pregnancy is a serious public health problem, but the country has made a monumental effort to counsel adolescents on pregnancy prevention and provide them with contraception. For those who do become pregnant, they are counseled after their baby is born, and almost all leave the delivery facility with a family planning method.

Arellano uses the injectable contraceptive Depo Provera every three months and now promotes family planning amongst her peers. She says: “I love my daughter, but I don’t want to get pregnant again until I am older.”

Though it is the second poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, Nicaragua—thanks to the efforts of Arellano, Hernández and many others—reports family planning indicators that surpass much richer countries. And, despite its poverty, Nicaragua has lower maternal mortality and a number of better health indicators than regional averages.

Nicaragua’s USAID family planning program ended in September 2012. The 2008 phase-out strategy not only ensured that the gains of the past would be protected for the future, but that improvements will continue to be achieved.

“The future is bright for women and children in Nicaragua as well as other countries that have graduated from USAID family planning assistance. Their health is something that truly deserves celebration,” says USAID/Nicaragua Mission Director Arthur Brown.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.