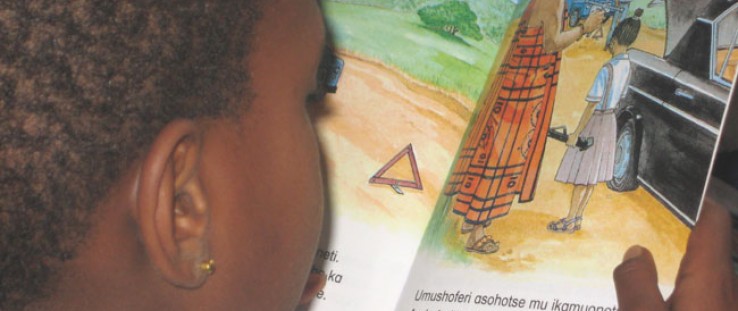

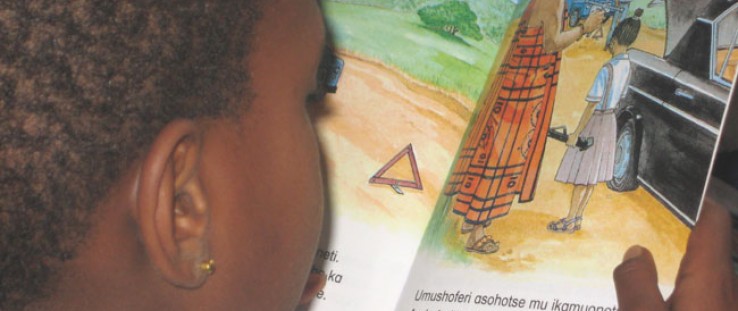

Textbook distributor Drakkar Ltd. is working to provide Rwandan children with books written in their native language.

Drakkar Ltd.

Textbook distributor Drakkar Ltd. is working to provide Rwandan children with books written in their native language.

Drakkar Ltd.

Textbook distributor Drakkar Ltd. is working to provide Rwandan children with books written in their native language.

Drakkar Ltd.

Textbook distributor Drakkar Ltd. is working to provide Rwandan children with books written in their native language.

Drakkar Ltd.

Drakkar Ltd.Local Language Books

Country: Rwanda

Grant Amount: $259,657

Mission: Ensuring that children in Rwanda have access to interesting books written in their mother tongue.

Imagine how difficult it would have been for you to learn to read if, upon entering school, the only books available were written in a foreign language. Though still grappling with your first language, you would be expected to recite and comprehend passages in an unfamiliar language. Valuable years in the early grades would be lost.

In Rwanda, English replaced French as the official language of instruction in 2008. But in 2011, the predominant local language, Kinyarwanda, spoken by all three ethnic groups of Rwanda—Hutu, Tutsi and Twa—became the official teaching language for the first three years of primary school. Rwandan children are now expected to read in both languages, starting their schooling in Kinyarwanda, and then switching to English in grade 4, at which point they are expected to have become proficient enough to study in it.

Despite this shift towards embracing Kinyarwanda in the early primary grades, there remains a dearth of relevant, high-quality, culturally appropriate instructional materials in the language.

Rwandan textbook distributor Drakkar Ltd. is trying to address these combined challenges with a plan to ensure that children in approximately 300 primary schools in four of the country’s 30 districts have access to materials written in Kinyarwanda. “Very few stories for children written in Kinyarwanda by Rwandans are available,” said Helle Dahl Rasmussen, project manager at Drakkar. “We see it [as] essential to be able to read in your mother tongue, especially at an early age.

”There is also an acute literacy problem: An early-grade reading assessment conducted in Rwanda in March 2011 indicated that after three full years of instruction, 13 percent of students surveyed in grade 4 could not read a single word of second grade- to third grade-level text in Kinyarwanda. Another 13 percent were reading less than 15 words per minute in Kinyarwanda, far below the approximate 45-60 words per minute range considered the minimum level of fluency in either Kinyarwanda or English.

In September, Drakkar had one of 32 winning projects selected from 450 submissions to improve literacy in over 20 countries as part of USAID’s All Children Reading Grand Challenge. Through its support of mother-tongue literature, the company, which was founded in 2006, hopes to promote a greater culture of reading in a country where illiteracy is widespread.

Not Just Translation

Research, including that of RTI International, into the efficacy of mother-tongue instruction in early primary grades backs up Rasmussen’s claim. In fact, learning in a mother-tongue language capitalizes on what a child already knows before their schooling begins. When children enter school, they are equipped with a working vocabulary and a general ability to communicate in their mother tongue. By teaching in a language that a child speaks, thinks and understands, he or she is able to actively engage in the classroom. The child smoothly transitions between home and school, their culture and traditional knowledge validated and reinforced in the classroom. After mastering their mother-tongue language, children are able to rapidly learn to read and write in a second language.

With the evidence in hand, Drakkar first plans to translate 58,000 readers, or textbooks with reading exercises, from French, Kiswahili and Amharic into Kinyarwanda. The readers, from the popular Junior African Writers Series, target children in primary grades—the first six years of education. About 300 schools in Rwanda with limited access to supplementary reading materials will receive the readers. Teachers will be trained at each school to use the materials to improve students’ reading skills, with the potential of reaching over 180,000 primary grade students.

And translation is just the beginning of Drakkar’s plans to bring childhood reading into the Rwandan mainstream. As an early initiative to cultivate local talent, Drakkar plans to sponsor an annual book-writing competition. Semi-finalists will be given writing seminars to improve their stories, and six winners across the country—three children and three adult authors—will have their stories published through Drakkar’s partnership with Pearson Publishing.

“At the moment, limited Rwandan authors for children exist,” said Rasmussen. “This project will identify and award those children who have the talent for writing and may become future Rwandan authors.” The end goal is to foster a national market for Kinyarwanda children’s books so that more books will eventually be written by Rwandan authors, which will in turn encourage more children to read.

“By leveraging partnerships and thinking creatively,” said Patrick Collins, USAID basic education team leader, “this local organization—and new USAID partner—will make great strides in filling the gap in culturally appropriate, local-language reading materials faced by Rwandan schools.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.