In Bishoftu, dozens of mappers, surveying almost 600,000 people in Ethiopia for trachoma, meet early in the morning before heading out to their allocated target areas.

© Dominic Nahr/Magnum/Sightsavers

In Bishoftu, dozens of mappers, surveying almost 600,000 people in Ethiopia for trachoma, meet early in the morning before heading out to their allocated target areas.

© Dominic Nahr/Magnum/Sightsavers

In Bishoftu, dozens of mappers, surveying almost 600,000 people in Ethiopia for trachoma, meet early in the morning before heading out to their allocated target areas.

© Dominic Nahr/Magnum/Sightsavers

In Bishoftu, dozens of mappers, surveying almost 600,000 people in Ethiopia for trachoma, meet early in the morning before heading out to their allocated target areas.

© Dominic Nahr/Magnum/Sightsavers

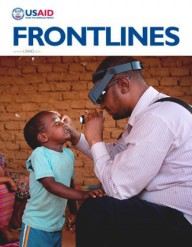

Anwar* is a 3-and-a-half-year-old Sudanese boy who last year was diagnosed as having the early stages of trachoma, a bacterial eye infection that, when left untreated, can lead to blindness. He is one of 2.6 million people who were screened by one of 550 trained field teams working in 29 countries over a three-year period to carry out the largest infectious disease survey ever undertaken.

“This colossal effort could not have happened without the steadfast commitment and collaboration of over 60 partners working together around the world,” explains Angela Weaver, senior technical adviser for USAID’s Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) Program and the Agency’s lead for trachoma elimination. “Mapping has been at the foundation of USAID’s NTD Program since it began 10 years ago. We must understand where treatment is needed before scaling up NTD programs. This is why we joined DFID, the U.K. Department for International Development, in supporting this unprecedented global survey.”

Preschool-aged children like Anwar, who often live in extreme poverty, are most at risk of contracting Chlamydia trachomatis, a bacterium that spreads through eye and nose discharge, hand contact and flies. With repeated episodes of infections over many years, it causes the eyelashes to turn inward, scraping the cornea, causing great pain and eventually leading to blindness. Anwar’s condition was detected in time and the worst was averted.

Trachoma is responsible for the visual impairment of about 2.2 million people, of whom 1.2 million are irreversibly blind. It has a direct impact on global productivity and is estimated to cost the world between $2.9 billion and $5.3 billion a year.

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP), launched in 2012, saw surveyors collect and transmit data from 2.6 million people in 29 countries. The survey sample was drawn from a population of 224 million perceived to be at risk. The Ministries of Health in the 29 countries spearheaded the effort by providing resources, such as transportation to remote areas, and partnering to standardize methodologies and data management. Academic institutions, non-profit organizations, foundations, donors and the private sector all contributed to this massive undertaking.

“Funded by the U.K. Government, in partnership with the U.S. and the WHO [World Health Organization], this creates a lasting platform, which will underpin the drive to eliminate blinding trachoma and will contribute to efforts to eliminate other NTDs,” says Dr. Caroline Harper, CEO of Sightsavers, the international NGO that led the mapping effort.

But initially not everyone was on board. “I think it took boldness to propose it, and courage to fund it,” says Dr. Anthony Solomon, chief scientist of the GTMP who is currently leading trachoma elimination efforts at WHO.

“We suggested that, in three years, we would do more to establish the global epidemiology of trachoma than what had been done in the previous 30 years,” he explained. “We promised to do it well, with global standardization and the utmost attention to partnerships principles and the rights of national governments to lead.”

Detect, Treat, Eliminate

In 1996, the WHO and select partners formed the Alliance for the Global Elimination of Blinding Trachoma by 2020 (GET 2020). This led to a strategy known as SAFE: Surgery for the blinding phase of the disease, Antibiotics to treat infections, Facial cleanliness and Environmental improvements such as access to clean water and sanitation. Pfizer Inc. propelled this effort when it launched a global donation program for Zithromax (azithromycin), the antibiotic used to treat trachoma.

Similar to the other NTDs covered by USAID’s NTD Program, communities endemic for trachoma are targeted for treatment. This typically involves three to five years of mass drug administration delivered once per year at the community level. Data from the global mapping exercise identified 100 million people that require treatment to prevent blindness from trachoma.

“GTMP provides us with critical information for production planning,” says Darren Back of Pfizer. “Manufacturing for the antibiotic is planned up to two years in advance of donation, and in order to meet the scaled up volume needed by 2020, we need to know the number of people that are still at risk for trachoma. Data provided by GTMP helps us manufacture and ensure that the right amount of antibiotic will be available for endemic communities around the world.”

USAID’s financial, technical and leadership support to the GTMP was delivered through the ENVISION project led by RTI International. It provides technical assistance in 19 countries focusing on the control and elimination of the NTDs targeted by USAID, including trachoma.

The collaboration with the GTMP enabled partners to harmonize technical approaches to follow WHO guidelines and provide additional funding where needed. “We now know what it takes to eliminate this blinding disease and we have the evidence that our partnership works and will get us there,” says Lisa Rotondo, director of the ENVISION project at RTI.

On the ground, that translates to more people getting care for what is a proven treatable disease.

“Tanzania has benefited greatly from the GTMP surveys, especially through the mainstreaming of electronic data collection,” says Dr. Edward Kirumbi, NTD program officer at the Tanzania Ministry of Health. “The GTMP methods and training have provided capacity for Tanzania to rapidly undertake trachoma surveys in the future. As a result, Tanzania is now on track to achieving the GET 2020 objectives.”

USAID and DFID are now focused on partnering to leverage the outcome of this joint exercise. “Collaborating to deliver a global map of trachoma is a great achievement, but we won’t stop here,” says Iain Jones from DFID. “The trachoma mapping tells us that 100 more million people are at risk of blindness from trachoma. What we need is more investment from donors and national governments to implement the SAFE strategy for the people who need it. The mapping has been a catalyst for this.”

*Last name not available.

Dr. Bilghisa Elkhair in Her Own Words

Dr. Bilghisa Elkhair is the national control program coordinator for the Ministry of Health in Sudan, and led the global trachoma mapping teams that examined 72,000 people in Sudan. Here’s how she’s fighting trachoma.

I am 43 years old and I am from Khartoum. I work for the Sudan Federal Ministry of Health and I am a trained ophthalmologist. The purpose of the mapping was to see if we have trachoma, and if we do, what is the magnitude of it, in order to determine what we need to do next. If we have trachoma cases, we want to eliminate it by 2020.

As the national coordinator, first I had to train graders in how to detect trachoma indicators by examining people and teaching them how to invert the eye to determine whether or not they have trachoma.

Secondly, I had to join the teams as a technical controller for quality assurance and verify that everything is being done to a specific standard. The teams consisted of one grader who is responsible for detecting the size of the trachoma; one recorder who is responsible for registering the result obtained per household. A facilitator joined us from the community and introduced us to each household. We also had two volunteers from the village itself.

In each village, we selected 30 neighboring households. If we found active trachoma, we administered tetracycline ointment. If we find indicators that the trachoma is more serious, we refer patients for surgery to the nearest eye care facility. During our screening, if we found any other sight-related problems, we referred patients to the hospital for further treatment. After we completed a household information and created a file for each member of the household, we sent the information directly for data analysis.

The greatest challenge we faced in the Khartoum mapping is having to travel far distances. Some outskirts of Khartoum are four hours away from the center of the city. People in general have been very helpful to us as they are used to people coming to carry out vaccinations.

We have mapped nearly all of Sudan. This is a big country and our job is important. My wish is to see Sudan free of trachoma because it is preventable and treatable.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.