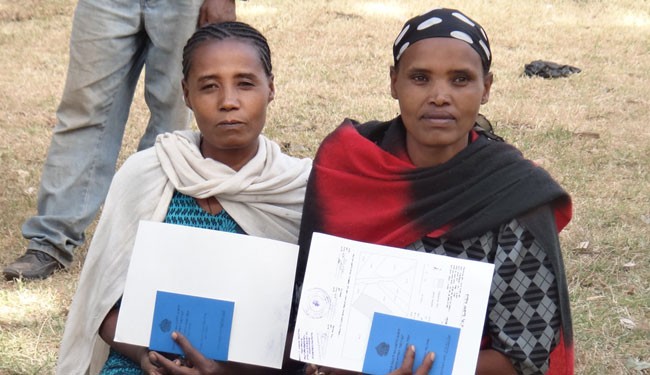

Asilya Gemmal, 14, of Gure Tebeno Union, proudly displays her land certificate obtained from the Ethiopian Government with USAID assistance.

credit: Links Media

Asilya Gemmal, 14, of Gure Tebeno Union, proudly displays her land certificate obtained from the Ethiopian Government with USAID assistance.

credit: Links Media

Asilya Gemmal, 14, of Gure Tebeno Union, proudly displays her land certificate obtained from the Ethiopian Government with USAID assistance.

credit: Links Media

Asilya Gemmal, 14, of Gure Tebeno Union, proudly displays her land certificate obtained from the Ethiopian Government with USAID assistance.

credit: Links Media

Property rights are proving to be a solid foundation for economic empowerment for individuals, corporations and nations, and a potential solution to shore up food security in developing countries. International guidelines adopted earlier this year address this issue.

Changing the World, One Property Right at a Time

New international guidelines adopted earlier this year are expected to pave the way for “landowners” to establish clearer rights to land and other resources in developing countries. That seemingly simple act—multiplied many times over in countries across the globe—could have profound consequences for the economies of developing countries, and reverse the trend of speculators snatching land without permission from the people who have historically considered it their own.

Land grabbing, as it is often called, happens every day in the developing world where weak laws and policies allow businesses and governments—through naiveté or outright greed—to latch on to property that belongs to someone else, and to sell or lease it to the highest bidder.

Adopted in May by the U.N. Committee on World Food Security, the 35-page document sets out principles to guide countries in designing and implementing laws that govern property rights over land, fisheries and forests for agricultural and other uses.

As it is officially known, the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security is designed “so that both investors can invest with some kind of certainty that their investments will be secure and, at the same time, those people who hold the resources or the assets—the people who have the land in the countries where we work—will also have some certainty that they will be able to benefit from the investments that are made,” says Gregory Myers, USAID’s division chief for land tenure and property rights and chair of the negotiations for the guidelines.

USAID is keenly interested in the guidelines, not only because of the inherent economic benefits of secure property rights for individuals and communities, but because of what that can mean for the Feed the Future initiative, the U.S. Government’s effort to ramp up agricultural development in food-insecure countries.

“In many ways, that’s really at the heart of our (Feed the Future) strategy—on one hand encouraging the private sector, and on the other hand supporting smallholder farmers,” Myers said.

“Between 800 million and a billion people go to bed hungry at night, and the number is growing,” he explained. “Clearly, we need to do something to promote agriculture … but that means there has to be investment in agriculture. So the bottom line is that we have to find a way to bring private-sector investment into this equation. And the only way that’s going to happen sustainably and in a way that’s not going to lead to a lot of violence or conflict is that we’re going to have to address the issue of property rights.”

Land Deals on the Rise

Today, estimates of land ac-quired for investment in developing countries are between 50 million hectares in a World Bank study and 250 million hectares from civil society organization estimates, both reported in 2011. The range is so large, in part, because many countries where this is happening have dysfunctional record-keeping systems and don’t recognize informal property rights.

An International Land Coalition study published in late 2011 concluded that, of the land deals researchers could track, 78 percent were purchased for agriculture production—mostly for biofuels, not food.

One of the most high-profile and controversial land acquisitions happened in Madagascar when a South Korean company announced it would lease 1.3 million hectares of land to grow products it would export back home. The scheme played a role in the overthrow of the Ravalomanana administration in 2009; his successor canceled the land deal, which would have tied up about half of Madagascar’s arable land for 99 years.

Organizations that monitor the land deals say smaller acquisitions pitting Goliath companies against David landowners occur regularly. There are also disputes that pit legitimate landowners against each other.

“People sell one land to two or three persons and nothing happens to them,” said Banny Minely, who lives in the town of Sedekan in Liberia, one of the places where USAID is helping landowners formalize their property rights. “The Government of Liberia should institute punitive measures to curtail double land sale. People should know their land and property rights.”

Minely says the boundary disputes are many: “Clans versus clans, towns versus towns, and individuals versus individuals. These disputes in some instances turn violent and people die in the process.”

Related Content

USAID Securing Land Tenure and Resource Rights

Land Tenure: from ImpactBlog

International Land Coalition

Video on USAID’s land-tenure work in Ethiopia

Adds Myers: “It’s one of those human rights issues that can be just as (highly) charged as other kinds of human rights issues—where people disappear all the time when they try to claim their land rights in many of the countries where we’re working.”

Land Grabbing, 21st Century Style

“It’s a phenomenon that’s been going on since time immemorial. But the size, the scale and the quickness with which all this took place was extraordinary,” Myers said of land acquisitions that occurred over the last few years.

It began with the global recession in 2007 and 2008. The economy tanked, leaving many investors broke. For those with substantial sums left to spend, the question became where to invest with the least amount of risk—and the most potential for profit.

“In those years, when the equity markets were bottoming and people were essentially looking for new investment opportunities, a lot of businesses around the world—private companies, sovereign wealth funds—started to look for investments in hard assets, which would be land or agriculture, forests, other hard commodities,” Myers said.

Africa was the epicenter of such buys. The practice became known as land grabbing, a retro name that often led to embarrassment for any companies whose purchase or lease ended up in the press. While some businesses and wealth funds were indeed looking to score big at the expense of small landowners, others found themselves inadvertently at odds with land-rights issues.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.