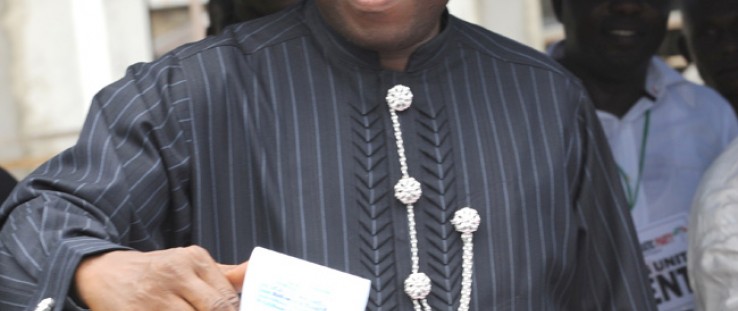

Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan casts his vote for president in Ogbia district, Bayelsa state, April 16, 2011. The following month, Jonathan signed the country's Freedom of Information bill into law.

Pius Utomi Ekpei, AFP

Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan casts his vote for president in Ogbia district, Bayelsa state, April 16, 2011. The following month, Jonathan signed the country's Freedom of Information bill into law.

Pius Utomi Ekpei, AFP

Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan casts his vote for president in Ogbia district, Bayelsa state, April 16, 2011. The following month, Jonathan signed the country's Freedom of Information bill into law.

Pius Utomi Ekpei, AFP

Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan casts his vote for president in Ogbia district, Bayelsa state, April 16, 2011. The following month, Jonathan signed the country's Freedom of Information bill into law.

Pius Utomi Ekpei, AFP

In February 2011, Nigeria’s House of Representatives responded to Nigerians’ call for greater transparency and accountability by passing the Freedom of Information (FOI) bill by a voice vote with no dissents. A Senate vote concurred the next month.

President Goodluck Jonathan signed a harmonized version of the bill into law on May 28, just before he took office for his first full tenure. Had he not done so on that date, the bill would have had to be reintroduced to the new National Assembly for fresh deliberations.

The journey for the FOI law has been a tough and hard fought one, languishing in the National Assembly for over 11 years, including three parliamentary sessions, five public hearings, and a presidential veto. In the end, the landmark legislation overrides the antiquated Official Secrets Act of 1911. For the first time, public institutions are legally obliged to keep proper records and must respond to requests for information within seven days.

Celebrations by all stakeholders, including journalists, civil society organizations, and champion lawmakers have taken place across the country. All agree that the FOI law is a significant development in the quest for accountability and transparency in public service and, by extension, good governance.

Nobel Prize-winning writer Wole Soyinka, who once ran a newspaper operation out of his garage, told NEXT newspaper in August 2011 that the law will help to “shred the web of silence” over government business in Nigeria, thereby encouraging public scrutiny of governance. “The swagger of indifference will give way to nervous glances over the shoulder,” he was quoted as saying. The law makes public records and certain other government-held information more freely available to the public. It provides broad rights of access, clear procedures to follow, and exceptions that acknowledge no right is absolute. It also importantly provides for the protection of whistle-blowers. Citizens can now access information that will greatly enhance transparency and accountability at all levels of government.

Because the law is under a year old, stakeholders have had little time to find out how government would respond to FOI requests. However, one NGO, Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP), recently tested the new law by asking for information on how stolen assets recovered by successive governments were used.

SERAP’s request to the accountant general would have simply been ignored under the Official Secrets Act. However, in this instance, the accountant general sent a letter stating that the request was “being examined alongside the provisions of the cited Freedom of Information (FOI) Act to appropriately determine the nature of information to release.” While this does not respond to the inquiry, it has made government more aware of the need to address such inquiries promptly.

The federal government, bowing to pressure from civil society, has just inaugurated an inter-ministerial committee headed by the attorney general and minister of justice to fashion operational guidelines for implementing the act in all government ministries, departments, and agencies. The committee is also tasked with preparing a road map for sensitizing and training public officers on the act and developing a framework to benchmark its implementation.

Eleven Years to Passage

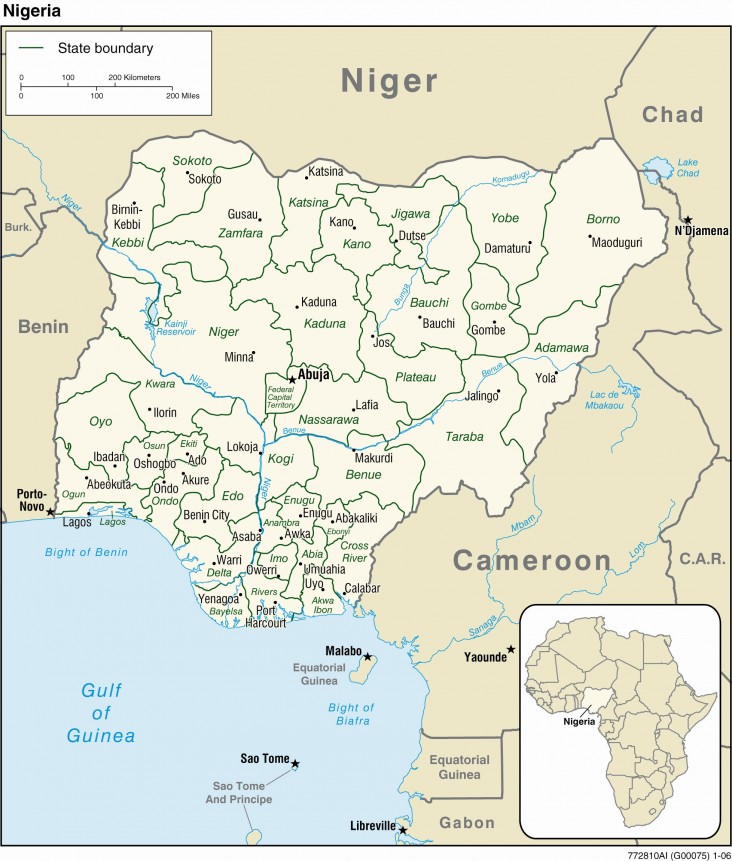

The lack of transparency, accountability, and fiscal responsibility in managing government revenues at all levels has set back Nigeria’s economic development by decades. In its quest to help the country address corruption and to bring about accountability and transparency in public service, USAID/Nigeria’s 11-year campaign that ended in the passage of the landmark FOI law was hard fought and heavily contested. The USAID mission established a broad coalition of civil society organizations and other stakeholders to work on passage of the bill and to inform the public so that they could make their opinions known to the government.

With USAID assistance, the FOI bill was nearly enacted in 2002, but action stopped because of procedural technicalities in the House of Representatives. Further progress was checked by an 80-percent turnover in the National Assembly following the 2003 elections. This meant that USAID/Nigeria and its civil society coalition had to roll up their sleeves to target reform-minded legislators who could help get the FOI bill back on the floor of the National Assembly. But the way forward was blocked as politicians were wary of the law being used to expose corrupt and ineffective governments.

An Historic Step

When the FOI law finally was enacted in 2011, it was called an historic step forward in the push to establish accountable, transparent governance. In just a few short months, Nigeria’s minister of finance published the budget allocations to the three tiers of government, providing a detailed account of funding and a roadmap to help journalists and likeminded citizens “follow the money.” Monthly allocations to the federal, state, and local governments were last published during the Obasanjo presidency four years earlier.

This transparency enables Nigerian citizens to follow their government’s fiscal allocations from the federal level down to the grassroots local governments. Social Action, an NGO, has hailed this move as a complement to the tenets of the FOI law as it realizes that access to fiscal information is a right of the Nigerian citizenry and would contribute to creating the desired public sensitivity to governance, transparency, and accountability in Nigeria.

USAID is now working with civil society and government to ensure the implementation of the law. One of those partners, Media Rights Agenda, has long been a champion of the FOI Act, and this year won the prestigious Pan-African Award in South Africa for “its tireless struggles culminating in the passage of Nigeria’s Freedom of Information Act in May 2011.”

On Nov. 15, USAID/Nigeria and Media Rights Agenda launched an easy-to-navigate application that allows Java-enabled mobile phone users to download the entire FOI law to their devices. With over 93 million active mobile telephone lines in Nigeria, the application is a powerful tool to help make the law available to the vast majority of Nigerians at no cost.

Improving public awareness of and familiarity with the provisions of the act should translate into a significant increase in the number of people using the law to seek information from public institutions and private entities.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.