Workers from the Independent Election Commission count ballots in Kabul.

USAID

Workers from the Independent Election Commission count ballots in Kabul.

USAID

Workers from the Independent Election Commission count ballots in Kabul.

USAID

Workers from the Independent Election Commission count ballots in Kabul.

USAID

When Malalai* was a child, she was taught that government was a man’s business. These lessons were reinforced by the Taliban, who banned Afghan women from stepping foot in polling centers. “We were told elections are meaningless for women,” Malalai said. Even after the Taliban’s fall, Malalai continued to follow the rules instilled by her upbringing. She did not vote in the 2004 and 2009 presidential elections.

But 2014 marked a change for Malalai, who is in her early thirties. The mother of four from the Chaperhar district of Kabul cast a ballot for the first time.

She wasn’t alone. During Afghanistan’s April general election, approximately 2.4 million Afghan women voted, accounting for approximately 38 percent of total turnout, according to the Independent Election Commission (IEC). This level of participation by women voters was the highest in Afghan history, evidence of a decisive shift in the roles women play in their country, experts say.

A Wall Street Journal article on the election season summed up why 2014 was a watershed moment: “Under the Taliban, Afghan women were barred from work, let alone political office.”

Today, Afghan women are not just voting. Some are running for public office—and winning.

Habiba Sarobi, the former governor of Bamyan province and a 2014 vice presidential candidate, attracted a sizeable number of votes from both genders by delivering lively, poignant campaign speeches. Speaking to British newspaper The Independent, she described her motivation for running. “The situation for women pushed me to fight for women’s rights and become a women’s activist,” she was quoted as saying. “We lost everything, that’s why I wanted to fight to get back everything we had lost.”

This year, 308 women ran for provincial council seats and 97 won positions. Many benefited from USAID training that helped women candidates develop and manage their campaigns, including providing methods for generating campaign funding and connecting with voters.

This metamorphosis in women’s political influence bled into the platforms of every serious contender for office, from the provincial councils to the presidential candidates. “This time, from the beginning, all of them [the politicians] have been talking about women’s rights,” said Hasina Safi, head of the Afghanistan Women’s Network, in comments to The New York Times. “They have really figured out that women count.”

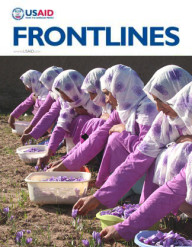

Women did not stop at voting and campaigning. They also served in electoral management bodies in their villages, districts and the capital, helping count ballots, check registrations and report cases of possible fraud. Afghan women were active members of civil society organizations, provided timely updates and critical analysis as journalists and bloggers, and spoke out as forthright policy advocates.

With the support of the international community, Afghan women have also secured consequential roles as election overseers and watchdogs. Since 2010, the United States has committed more than $100 million to improve election administration and transparency by training officials in Afghanistan’s electoral bodies and providing them with equipment such as vote tally software for the National Tally Center, which calculated election results. Of the 2,200 USAID-funded independent monitors that were in the field on Election Day, 947 were women. USAID also trained another 8,000 women observers from both presidential campaigns, which added an additional level of security.

USAID also helped to establish a gender office inside the IEC, tasked with educating Afghan women on the process of voting, and recruiting and training female election administration staff. The efforts of the gender office paid off—nearly doubling the number of female members of the IEC from 18 percent in 2009 to 33 percent five years later. During the 2014 vote, female election staff served in all 34 provinces of the country.

The IEC’s female staff members have to be courageous. Jemila* started with the IEC after graduating from university. She had only served for seven months before threats mutated into reality. Jemila was shot during an insurgent attack on the IEC’s regional office in the Darulaman district of Kabul. Despite her injuries, she rushed back to the office as soon as she was able.

“I wanted to use what I learned at university to improve the country,” she explained. “Women have the same rights as men, and it’s important for us to participate in the election process. It’s our country, and the future of our country is at stake.”

In some of Afghanistan’s most conservative districts, all-female IEC staff greeted female voters, checked ID cards, inked fingers and gave instructions on how to cast a ballot. At the end of the day, men and women IEC staff worked side-by-side tallying votes and breaking down polling centers.

In the past year, the heightened level of public discourse around women’s political participation was palpable. Civil society organizations ran ad campaigns on national television and local radio encouraging women to vote. Advocacy groups educated fellow citizens and engaged with politicians and election officials. USAID helped many of these groups to organize meetings with local officials, candidates and political parties.

USAID provides support to:

- election management bodies to conduct transparent, inclusive and credible elections

- political parties, independent candidates and civil society to engage in the political process

- NGOs to educate and encourage citizens to vote and participate in Afghanistan’s governance.

The Future Leaders Organization (FLO), a non-profit civic action organization based in Kabul, led community events throughout the country, ran gender sensitization workshops for civil servants and organized talks in communities between citizens and government officials.

“In every democratic society, both men and women should be given the chance to vote,” said Shakila Baraksai, the leader of the FLO. “If women are not allowed to participate and compete in the national processes, our country will be protecting citizens’ rights only symbolically.”

Malalai was resolute when asked why this election had changed her mind on voting. “After awareness campaigns, we knew how our participation could make a difference,” she said, pausing to consider how her views had transformed in the course of 12 years. “I did this for my children. I don’t regret it.”

*Full names withheld by request.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.