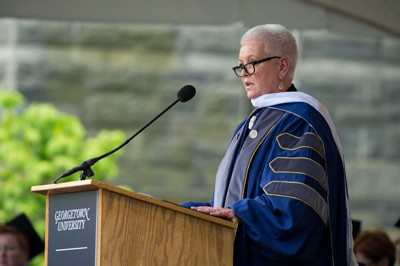

Just as a head’s up, this feels really good. Thank you all, and thank you President DeGioia. I am incredibly honored to be part of this special occasion, and I want to thank Dean Montgomery for inviting me to be here today. And I want to thank you for not making me wear a hat, which I was worried might make me look like a bowling pin. But you all look wonderful.

Seriously, you do. Congratulations to all of the graduates, and to your families and loved ones as well. We all know how stressful it is to be around grad students, so you deserve congratulations and our thanks.

This is a daunting time to dive into the public policy world. As a field, it’s more competitive than it has probably ever been. And the challenges are about as big as I can remember. So I want to start by saying thank you to all of the graduates, for deepening the bench, and for choosing to help find the solutions to those challenges. We’re going to need you.

A few weeks ago I was speaking to a group of humanitarian NGOs about some of those challenges and how we might tackle them – from increasing attacks against aid workers and civilians to the massive refugee crisis. And after I finished speaking, a Palestinian man came up to me. He told me he had grown up in a refugee camp, where he first saw the USAID emblem – two hands joined together in peace and friendship.

The man said that the image had comforted him during some of his toughest times, so much so that he wrote a poem about it years later. Now, he said, he has broad shoulders upon which to carry the burden of others because those hands of kindness reached out to him as a boy.

I’ve heard stories like this over and over ever since becoming Administrator and throughout my career. Like the story of Syrian refugee children able to continue their education in Jordan – all because a principal opened the doors of her already crowded school. “I will register your daughter,” she told one mother, “if you bring a chair for her.”

Or the story of a family in rural Rwanda, able to turn the lights on in their home for the first time because a business saw opportunity where others had seen only obstacles, and worked to create a market where there wasn’t one before. Or a woman farmer in Ethiopia who was able to increase her crop yields and better support her family and community, in part because the U.S. Government and NGOs across this country joined with partners all over the globe to invest in agriculture and nutrition.

These kinds of stories are not unique to the developing world either. It turns out, we all struggle with the same questions; we all face the same challenges. And we are all connected by our shared humanity.

Today, in states from Arizona to Maine, “Refugees Welcome” signs hang proudly at churches, businesses, and homes – a beacon of hope shining through dark rhetoric. And a family scarred by war and violence, and tired of fleeing, can find warmth and peace in the embrace of another family.

A young mother in Washington, D.C. with a heart condition is able to get the health care she needs for the first time because someone in public policy in her government made affordable health insurance for all a policy priority.

These are stories of the world at its best, stories of public policy and public service – whether through government, the private sector, NGOs, local communities, or institutions of faith – working as they should.

Now for me, the most rewarding work I’ve done has been when I’ve played some small part in stories like these. And I’m happy to say it has accounted for about 90% of my career – I’ll leave out the mailroom in college, though I will say that I was instrumental in getting the packages where they needed to go.

Sometimes my work was as a witness and storyteller, sometimes as an advocate, sometimes as a public servant. But I have always felt most fulfilled when I was striving toward some higher ideal or goal that would ultimately benefit someone other than myself.

I thought about this as I was preparing for this speech. And I thought long and hard about the advice I wanted to share with you. If you add up the years in the introduction that was given, I’m older than I used to be, and I today have a lot of young people coming through my door, telling me where they might want to end up and asking for advice on the right next steps. So it isn’t the first time I’ve thought about this, and I want to tell you the same thing I tell them.

As graduates of a school of public policy – and one of the finest at that – you will have plenty of opportunities in front of you to seek personal pride, and to fulfill personal ambitions. But you will also have opportunities to leave the world a better place than you found it.

I hope you’ll remember that this is a privilege, and an extraordinary one at that. And I hope you’ll remember that there is something bigger than you out there, and that it’s worth pursuing.

Because, as it turns out, when you remove yourself from the equation a bit, and when you remember that everything really isn’t about you, that’s when you do your best work. And that’s when you can have a real impact on the world.

Now I don’t mean that you should be completely selfless. You need to pay your bills, take care of your families, and save for the future. But once you do that, don’t just look for opportunities that will look good on your resumes. Look for the opportunities that challenge and stretch you; look for the opportunities that allow you to change the world for the better.

This isn’t easy. With the day-to-day pressures you face – and whether we’re talking about uncertainty, student debt, or a competitive job market, I’m the first to admit those pressures are greater today than anything I had to face when I started out. These pressures make it seem as if always plotting to get that title change or salary bump is necessary for survival. But there is such a thing as being overly intentional. If you’re always calculating that next step, there is little room for new experiences, and little opportunity to let your curiosity drive you.

In my case, my parents probably thought I was a little bit too curious. But when that curiosity pushed me to travel outside of the United States, I got my first real glimpse at the inequities of the world. I saw war, famine, and gross injustice. I saw a people who had literally nothing, simply because they were caught on the wrong side of the battle lines in a war the world forgot.

The differences between what I witnessed in Ethiopia and Sudan and my relatively sheltered upbringing in Columbus, Ohio, were enough to grab my attention and hold it for the rest of my life. And I’ll admit this could be just a fluke, but I have followed that initial curiosity my entire career, with new opportunities and experiences emerging around every corner. And I’m still following it today.

That’s an approach that, I think, can make us more effective policymakers. For one, thinking beyond yourself and your own experiences teaches you the value of diversity, and the tremendous importance of perspectives other than your own. It can also help you work with people with whom you disagree. And believe me, there will be many of them. It will be your responsibility to hear and understand their perspectives, and use what you learn to shape your own thinking.

Thinking fo something bigger than yourself can also help you avoid the pitfalls of well-intentioned ignorance. Too often, politics seems like a sport, with one side scoring points against the other. But I hope that’s not a lesson you learned here in Washington, because governing is never a game. And winning the argument is never more important than getting something good done.

And the truth is you’re going to limit your progress if you just talk to people where you think they should be; you have to meet them where they are.

And to do that, all of us have to listen. Listen better, and more. To practice good public policy is to analyze, craft, advocate, and implement. And each of those steps requires listening. To the facts – and yes, those are still important, to your critics, to the public, and, most importantly, to the people you serve.

I recently spent some time listening, and I’m better for it. In April, a young Bangladeshi man was murdered, along with his friend, in his home in Dhaka. He was brutally murdered in an act claimed by terrorists, all because he believed that every person - no matter who they loved or prayed to, no matter what they looked like or what class they were born into – that every person deserves to be treated with respect and dignity.

I believe that, too. I know that you do as well. But for this young man, that belief – and his willingness to act on it – got him killed.

His name was Xulhaz Mannan, and he worked for USAID, as one of our leaders in governance and democracy, and at the U.S. Embassy before that. I went to Bangladesh two weeks ago to visit our Mission there. I went to offer what was surely insufficient solace to his family, and to sit down with his colleagues to get a better sense of who this man was. I heard stories about his kindness and generosity at work, about his enthusiasm for his country and for meeting new people. About his activism for LGBT rights. He said simply, “My love doesn’t hurt you, but your hate hurts me.” I saw his desk, decorated with a bouquet of flowers that had long since died.

When I asked his colleagues about it, they said they had questioned it too, at first. But Xulhaz told them the flowers were dried, not dead. And they were beautiful. And it was his choice to see that beauty.

Weeks after his death, every single one of his colleagues was intent on being better, on doing more for the world. They want to look at things as he would – to see dried flowers where others see dead ones. They want to live up to his example, and to carry on his spirit through their work and service.

I understand that. Simply hearing his story made me want to do better by the world – just as he would have done.

So even in death, Xulhaz Mannan can inspire someone he never met in life. Even in death, he is able to have an impact on something bigger than him, to change the world for the better.

So the best advice that I can give you is to be like Xulhaz. Make the choice to see the good in the world, and make the choice to fight for it where you don’t see it.

There is great power in that choice. And that power is yours.

Finally, my sincere congratulations to all of you. But also, and importantly, my sincere thanks – as a public servant, advocate, and citizen – for all that you have done and will do. Thank you very much.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.