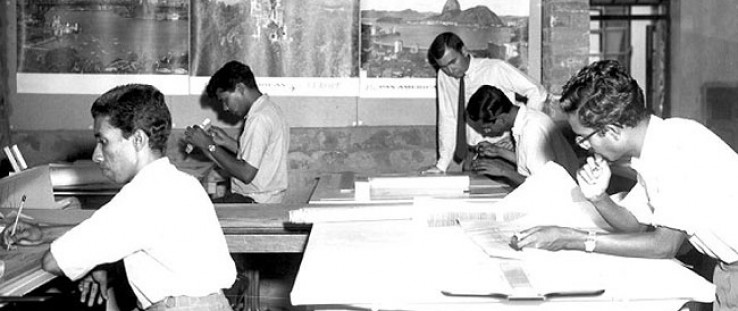

James Walden (standing) works with students in the design studio in 1962.

JAMES WALDEN

James Walden (standing) works with students in the design studio in 1962.

JAMES WALDEN

James Walden (standing) works with students in the design studio in 1962.

JAMES WALDEN

James Walden (standing) works with students in the design studio in 1962.

JAMES WALDEN

In the early 1960s, James Walden worked on a USAID-supported project to establish Bangladesh’s first school of architecture as part of the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET). Walden, who now owns his own architecture firm in Stamford, Conn., recently returned to the school to deliver a keynote address at its 50th anniversary commemoration.

Today, the BUET School of Architecture has a total enrollment of approximately 400 students and is one of the most prominent architecture programs in South Asia. It no longer receives USAID funding but is, in fact, making its own inroads in contributing to cost-effective and sustainable design for the developing world.

In 2009, a BUET team, led by associate professor Skeikh Ahsan ullah Mojumder, won first prize in an international architectural design contest, called “Design for the Children,” to develop an adaptable pediatric clinic that could be modified to fit different sites in East Africa. These two interviews together represent the completion of a circle—how a smart U.S. investment decades ago is continuing to pay dividends throughout the developing world.

USAID: What was Dhaka like when you arrived in the early 1960s, and how do you compare that to what it was like on your recent visit this past February?

JAMES WALDEN: At that time, there was probably only one multistory building in Dhaka, and that was where the British High Commission and USAID were located. There were few automobiles. Travel was common by rickshaw.

Everybody had somebody there, doing something. The Dutch had people there teaching people to build polders around villages to keep flood waters out. There was a group there from Harvard Business School talking to the government about how to organize their finances. [There was a] huge turmoil of discussion going on. At night, there was nothing to do, no television, no telephone, no movies, so we went to dinner parties and talked about what we were doing. It was fascinating to hear of all the different things that were going on to what was commonly referred to by the Harvard Business School as “jump starting” that economy.

By contrast, in the 50 years that elapsed, I was very humbled by my visit there. There are soaring skyscrapers like you would see in any other metropolis, and though there is still significant poverty, there are also extremely elegant hotels and the latest communications technology.

USAID: When you were working to establish the school, what did you expect or hope might grow out of your work?

Walden: Back in the 1960s, I had no idea what the outcome of our little program would be. In fact, today it’s a full five-year school of architecture and planning. It has its own building, its own faculty of almost 30 people, half of whom have PhDs. The student work that I saw was comparable to what I see when I’m invited to be a visiting critic here in the United States. Their computer technology is equal to what we have here.

When I went back in February, I spoke at a seminar attended by many of our former students and visitors from Singapore, India, China, from around the world. Everyone was very grateful for our work [Dik Vrooman, Dan Dunham, and me], and I was repeatedly told that we built a platform on which we could build the school of architecture that exists today.

In my view, the modest investment made by the United States in starting this program in the 1960s catalyzed a huge return.

USAID: How did you hear about the position in Dhaka, and was it a difficult decision to go there for this project?

Walden: I’d been in the Air Force, and had come back, and started work in Dallas, and was invited to go back to Texas A&M to teach design. And one day, I received a notice in my mailbox from the Office of Foreign Programs at Texas A&M announcing that the State Department wanted to start this school of architecture in some place called East Pakistan. I had no idea where East Pakistan was. But, you know, if you’re 21 years old, you’re bulletproof. You don’t care where it is. This is an adventure.

The big thing on my horizon was, here’s an opportunity to travel and, you know, who gets invited to start a school of architecture nowadays anywhere in the world? My wife Joan was an art teacher whose photograph is still prominently displayed there at the school now. So we were both excited about this opportunity. My son was 3 years old and my daughter was 7.

USAID: How was the project received at the time? Was there recognition of its importance?

Walden: There was a time shortly after I got there when we had a visiting ambassador—I don’t recall his name. All of the people from USAID-supported programs were invited to a meeting with him. And everybody went around saying what they were doing, and everybody was doing these important things. And Dik [Dik Vrooman, the head of the Texas A&M project team] got up and introduced himself, me and Dan [Dunham] and said that we were there to establish a school of architecture. The visiting ambassador literally threw up his hands and said, “What in God’s name are we doing establishing a school of architecture in this impoverished country?” And Dik was quick enough to point out—and in fact this was true—that a huge amount of money was being outlaid to foreign consultants, because there was a lot of building going on. So, economically, it made sense to build local architecture capacity by having a school of architecture.

USAID: What was the process like for recruiting students in those early years?

Walden: Starting with nothing, we went through the process of advertising for students, believing that we would be inundated—and we were—by applicants, and selecting the first class, the second class, and so on.

We also went to the vice chancellor when we were there and asked if it would be all right if we selected some women, and the vice chancellor, who was educated at MIT, gave us permission to do so. We admitted three women, all three of whom became practicing professionals. And the result of all this is that now the school is run by three women.

USAID: Can you tell us a bit about your students and some of the assignments you gave them?

Walden: I once assigned “build me a tower”—I don’t care what you use, but it has to be at least 3 feet tall. And the next thing I knew here was Ali Azad Chaudry sitting in the back of the classroom and he’s got a machete between his feet, and he’s taking bamboo and pulling little strips of bamboo like they were balsa wood. I was inspired! I still, to this day, keep a photo of the tower he created. I was just thrilled with the response.

One of the other assignments I did—and the result, designed by Wadeja Jafar, was the most beautiful thing I’d seen in a long time—was “design a school in a village using only products that could be delivered by country boat.” At that time, masonry was developed right on site. The only thing that needed to be transported was reinforcing rods for the roof and cement bags.

Every one of that first class eventually graduated, and every one of them now practices or has recently retired at a senior position in some place in the world. So that’s an impressive example of the ingenuity and drive of that group.

COMPANION ARTICLE

Read the accompanying interview with BUET Associate Professor Skeikh Ahsan ullah Mojumder.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.