Better crop yields are benefitting residents of northern Senegal, including the woman pictured here.

Olivier Asselin

Better crop yields are benefitting residents of northern Senegal, including the woman pictured here.

Olivier Asselin

Better crop yields are benefitting residents of northern Senegal, including the woman pictured here.

Olivier Asselin

Better crop yields are benefitting residents of northern Senegal, including the woman pictured here.

Olivier Asselin

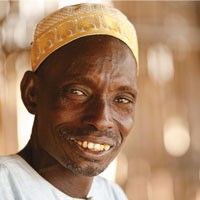

DIAWARA, Senegal — Mamadou Doucouré was born in France of Senegalese parents. As an adult, he longed to rediscover his roots and return to his familial home. Diawara, his ancestral village, is located in Senegal’s extreme northeast near the sand-swept border of Mauritania, a far cry from the glitzy restaurants and vibrant nightlife of Dakar, let alone the boulevards of Paris.

Passing on the Gift of Prosperity

Here, on the southern rim of the unforgiving Sahara Desert, food security is a matter of life and death. And here is where Doucouré found, through USAID, that he could make a difference in the quality of life for those in his ancestral community while building a successful business for his own family’s livelihood.

Feed the Future, the U.S. Government’s flagship food security initiative, seeks to reduce poverty and hunger in places like Doucouré’s village by accelerating growth in the agriculture sector. Under the Feed the Future strategy, USAID/Senegal developed a project called Yaajeende, signifying “abundance” in the region’s Pulaar language, to respond to specific nutritional challenges in high-priority areas. The project seeks to increase the amounts of nutritious foods being grown in these target zones as well as to improve the ability of the local people to use those foods to their maximum benefit. Rather than give handouts to local communities, the project improves the ability of private-sector companies to provide better products and services to these isolated areas.

“The mile between the market and the farm is the longest in terms of getting products, information and services down to the small producers who are often isolated in distant villages,” Doucouré said. “Working with USAID/Yaajeende, I can help companies bridge that gap and provide local farmers access to better products, services and information. Not only do I help companies sell products locally, but I work side by side with them to get the best results in the fields.”

To date, USAID has trained Doucouré and 200 others, including 25 women and 20 expatriates from other countries in the region, to be community-based service providers. USAID/Yaajeende recruits and trains these providers to act as a kind of intermediary between farmers and private companies in Senegal’s most food-insecure areas.

The service providers help farmers purchase better seeds, fertilizers and equipment; teach them new production techniques; faciliate access to credit; and broker the sale of crops to interested buyers. USAID expects to train up to 1,500 community-based service providers by the project’s end in 2015.

Turning the Distribution Model Upside Down

In the past, farmers in Senegal’s most food-insecure areas have been trapped in a cycle of humanitarian aid, not only because of frequent droughts, but also due to the poor quality of the seeds, fertilizers and tools available to them. Companies in Dakar that sell high-quality agricultural products have not expanded to the hardest hit regions since it is difficult to drum up enough business to make expansion worthwhile.

USAID’s service providers fill the gap by consolidating orders from a large number of local farmers, providing a financial incentive for companies to expand to new zones, and, consquently, furnishing local people with access to better products and services.

Community-based service providers are, in essence, sales representatives who work on behalf of both local communities and private companies, representing a community to a broad range of suppliers and buyers. They are elected by their peers based on their demonstrated talents in agriculture or business, and are trained in basic business skills by USAID and in technical skills by the private companies that use their services.

Once USAID identifies and trains the service provider, the Agency helps facilitate credit for his/her operations and simultaneously reaches out to the private companies, helping them understand how to use the service-provider network to increase sales. Finally, the project helps companies present their products and services to the local communities in order to generate interest.

Thus, the service provider plays multiple roles, acting as a sales broker for commercial products and services and as a technical consultant to producers. For their work, the providers receive commissions from both the producers and the suppliers.

The community-based service provider model turns the classic distribution model upside down by selecting the sales representatives from the communities rather than from the companies. It also builds on long-established relationships and allows for greater trust. Because he’s based locally, Doucouré has built enduring trust with his peers, and villagers are comfortable allowing him to collect communal money and negotiate important deals for seeds, fertilizers and tools. Because Doucouré’s revenues depend on keeping his local customers satisfied, he has a vested interest in establishing and sustaining a successful network of cultivators. If the villager farmers produce more and earn more, so does Doucouré.

“The Private Sector Will Ensure Food Security”

USAID is also using the community service-provider model to improve nutrition. Nutrition-focused service providers are negotiating with private companies to sell enriched flours for infants, micronutrient powders made from locally grown fruits, and water purification tablets. Sales of these products are already taking off in rural areas of Senegal, ensuring the long-term sustainability of the activity.

In addition to selling new products, some service providers have started business services such as crop spraying, irrigation system maintenance, livestock vaccination, land preparation and crop maintenance.

Better products and services translate into more productive agriculture and ultimately lead to more stable and more diverse food supplies. “In the long run, it is the private sector that will ensure food security,” USAID/Senegal Mission Director Henderson Patrick said. “Only through a market-based approach will rain-deficient areas like Northern Senegal be able to escape the cycle of humanitarian aid.”

Drawing on his USAID training, Doucouré recently negotiated a competitive price for high-yield maize hybrid seeds for which he earned a commission after marketing the seed to his fellow villagers in Diawara. “With these hybrid seeds, producers can greatly increase their yields and earn significantly higher profits if they use them properly,” he said.

To ensure that the farmers got the maximum benefit from these seeds, Doucouré worked hand-in-hand with them to apply the technical training that he received from the seed supplier. For the upcoming 2012 agricultural season, he plans to expand his business to include land preparation services.

USAID helped facilitate a $20,000 loan from local lender ACEP to help Doucouré purchase a tractor and a soil ripper. With these tools, he estimates that he can help more than 100 producers prepare their fields using conservation farming methods which will, in turn, increase their crop yields substaintially.

“This young man sets an example for everyone, and especially for expatriates reluctant to return to Senegal for fear of not finding a stable job,” Demba Dembele, a Diawara farmer, said of Doucouré. “He is effective, patient and passionate about farming. He knows how to work with us and with businessmen, too.”

USAID’s Zack Taylor contributed to this article.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.